Wild Western Tales 2: 101 Classic Western Stories Vol. 2 (Civitas Library Classics) Read online

Civitas Library Classics

WILD WESTERN TALES 2

101 Classic Western Stories Vol. 2

by Various

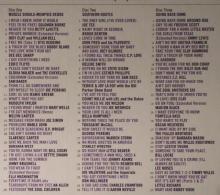

Table of Contents

A COLLEGE VAGABOND Andy Adams

RANGERING Andy Adams

SIEGERMAN’S PER CENT Andy Adams

THE DOUBLE TRAIL Andy Adams

THE PASSING OF PEG-LEG Andy Adams

THE SHADOW OF THE GREENBACK Robert Bar

THE REAL AND THE MAKE-BELIEVE Rex Beach

WITH BRIDGES BURNED Rex Beach

WITH INTEREST TO DATE Rex Beach

THE SPIRIT OF THE RANGE B.M. Bower

THE UNHEAVENLY TWINS B.M. Bower

WHEN THE COOK FELL ILL B.M. Bower

THE GHOST Max Brand

A PRAIRIE INFANTA Eva Wilder Brodhead

MARTIN GARRITY GETS EVEN Courtney Ryley Cooper

RANGER STYLE J. Allan Dunn

THE GOLDEN TRAIL J. Allan Dunn

A CRISIS FOR THE GUARD John Fox, Jr.

A PURPLE RHODODENDRON John Fox, Jr.

A TRICK O' TRADE John Fox, Jr.

CHRISTMAS EVE ON LONESOME John Fox, Jr.

CHRISTMAS NIGHT WITH SATAN John Fox, Jr.

COURTIN' ON CUTSHIN John Fox, Jr.

THE LAST STETSON John Fox, Jr.

A MISSOURI SCHOOLMARM Zane Grey

NONNEZOSHE, THE RAINBOW BRIDGE Zane Grey

TAPPAN'S BURRO Zane Grey

THE CAMP ROBBER Zane Grey

THE GREAT SLAVE Zane Grey

AN ESMERALDA OF ROCKY CANYON Bret Harte

A NIGHT AT WINGDAM Bret Harte

DICK SPINDLER'S FAMILY CHRISTMAS Bret Harte

LIBERTY JONES'S DISCOVERY Bret Harte

MR. JACK HAMLIN'S MEDIATION Bret Harte

THE ADVENTURE OF PADRE VINCENTIO Bret Harte

THE BOOM IN THE "CALAVERAS CLARION" Bret Harte

THE DEVIL AND THE BROKER Bret Harte

THE MYSTERY OF THE HACIENDA Bret Harte

THE SECRET OF SOBRIENTE'S WELL Bret Harte

THE SHERIFF OF SISKYOU Bret Harte

WHEN THE WATERS WERE UP AT "JULES'" Bret Harte

YOUNG ROBIN GRAY Bret Harte

PISTOL POLITICS Robert E. Howard

SHARP'S GUN SERENADE Robert E. Howard

TEXAS JOHN ALDEN Robert E. Howard

THE APACHE MOUNTAIN WAR Robert E. Howard

THE CONQUERIN' HERO OF THE HUMBOLTS Robert E. Howard

THE FEUD BUSTER Robert E. Howard

THE HAUNTED MOUNTAIN Robert E. Howard

THE RIOT AT COUGAR PAW Robert E. Howard

HOW COLONEL KATE WON HER SPURS Florence Finch Kelly

OUT OF SYMPATHY Florence Finch Kelly

OUT OF THE MOUTH OF BABES Florence Finch Kelly

POSEY Florence Finch Kelly

THE KID OF APACHE TEJU Florence Finch Kelly

THE RISE, FALL, AND REDEMPTION OF JOHNSON SIDES Florence Finch Kelly

THE STORY OF A CHINEE KID Florence Finch Kelly

CYNTHIANA, PET-NAMED ORIGINAL SIN Alfred Henry Lewis

DEAD SHOT BAKER Alfred Henry Lewis

HOW THE MOCKING BIRD WAS WON Alfred Henry Lewis

HOW TUTT SHOT TEXAS THOMPSON Alfred Henry Lewis

OLD MAN ENRIGHT'S UNCLE Alfred Henry Lewis

OLD MONTE, OFFICIAL DRUNKARD Alfred Henry Lewis

PROPRIETY PRATT, HYPNOTIST Alfred Henry Lewis

RED MIKE Alfred Henry Lewis

SPELLING BOOK BEN Alfred Henry Lewis

THAT TURNER PERSON Alfred Henry Lewis

THAT WOLFVILLE-RED DOG FOURTH Alfred Henry Lewis

A RIDE WITH A MAD HORSE IN A FREIGHT-CAR W. H. H. Murray

HOW DEACON TUBMAN AND PARSON WHITNEY CELEBRATED NEW YEAR'S W. H. H. Murray

THE LAST PROTEST Henry Oyen

THE WHISPERER Gilbert Parker

THE BLUE QUAIL OF THE CACTUS Frederic Remington

THE SOLEDAD GIRLS Frederic Remington

THE SPIRIT OF MAHONGUI Frederic Remington

THE STRANGE DAYS THAT CAME TO JIMMIE FRIDAY Frederic Remington

THE SEWING-MACHINE STORY Frank H. Spearman

MARY Horace Annesley Vachell

MINTIE Horace Annesley Vachell

OLD MAN BOBO'S MANDY Horace Annesley Vachell

ONE WHO DIED Horace Annesley Vachell

PAP SPOONER Horace Annesley Vachell

THE BABE Horace Annesley Vachell

THE BARON Horace Annesley Vachell

THE DUMBLES Horace Annesley Vachell

UNCLE JAP'S LILY Horace Annesley Vachell

WILKINS AND HIS DINAH Horace Annesley Vachell

THE RACE Stewart Edward White

THE RIVER-BOSS Stewart Edward White

THE RIVERMAN Stewart Edward White

THE SAVING GRACE Stewart Edward White

THE SCALER Stewart Edward White

THE TWO CARTRIDGES Stewart Edward White

A KINSMAN OF RED CLOUD Owen Wister

A PILGRIM ON THE GILA Owen Wister

HANK'S WOMAN Owen Wister

THE JIMMYJOHN BOSS Owen Wister

THE PROMISED LAND Owen Wister

THE SECOND MISSOURI COMPROMISE Owen Wister

THE SERENADE AT SISKIYOU Owen Wister

TWENTY MINUTES FOR REFRESHMENTS Owen Wister

Contents

A COLLEGE VAGABOND

By Andy Adams

The ease and apparent willingness with which some men revert to an aimless life can best be accounted for by the savage or barbarian instincts of our natures. The West has produced many types of the vagabond,--it might be excusable to say, won them from every condition of society. From the cultured East, with all the advantages which wealth and educational facilities can give to her sons, they flocked; from the South, with her pride of ancestry, they came; even the British Isles contributed their quota. There was something in the primitive West of a generation or more ago which satisfied them. Nowhere else could it be found, and once they adapted themselves to existing conditions, they were loath to return to former associations.

About the middle of the fifties, there graduated from one of our Eastern colleges a young man of wealthy and distinguished family. His college record was good, but close application to study during the last year had told on his general health. His ambition, coupled with a laudable desire to succeed, had buoyed up his strength until the final graduation day had passed.

Alexander Wells had the advantage of a good physical constitution. During the first year at college his reputation as an athlete had been firmly established by many a hard fought contest in the college games. The last two years he had not taken an active part in them, as his studies had required his complete attention. On his return home, it was thought by parents and sisters that rest and recreation would soon restore the health of this overworked young graduate, who was now two years past his majority. Two months of rest, however, failed to produce any improvement, but the family physician would not admit that there was immediate danger, and declared the trouble simply the result of overstudy, advising travel. This advice was very satisfactory to the young man, for he had a longing to see other sections of the country.

The elder Wells some years previously had become interested in western and southern real estate, and among other investments which he had made was the purchase of an old Spanish land grant on a stream called the Salado, west of San Antonio, Texas. These land grants were made by the crown of Spain to favorite subjects. They were known by name, which they always retained when changing ownership.

Some of these tracts were princely domains, and were bartered about as though worthless, often changing owners at the card-table.

So when travel was suggested to Wells, junior, he expressed a desire to visit this family possession, and possibly spend a winter in its warm climate. This decision was more easily reached from the fact that there was an abundance of game on the land, and being a devoted sportsman, his own consent was secured in advance. No other reason except that of health would ever have gained the consent of his mother to a six months' absence. But within a week after reaching the decision, the young man had left New York and was on his way to Texas. His route, both by water and rail, brought him only within eighty miles of his destination, and the rest of the distance he was obliged to travel by stage.

San Antonio at this time was a frontier village, with a mixed population, the Mexican being the most prominent inhabitant. There was much to be seen which was new and attractive to the young Easterner, and he tarried in it several days, enjoying its novel and picturesque life. The arrival and departure of the various stage lines for the accommodation of travelers like himself was of more than passing interest. They rattled in from Austin and Laredo. They were sometimes late from El Paso, six hundred miles to the westward. Probably a brush with the Indians, or the more to be dreaded Mexican bandits (for these stages carried treasure--gold and silver, the currency of the country), was the cause of the delay. Frequently they carried guards, whose presence was generally sufficient to command the respect of the average robber.

Then there were the freight trains, the motive power of which was mules and oxen. It was necessary to carry forward supplies and bring back the crude products of the country. The Chihuahua wagon was drawn sometimes by twelve, sometimes by twenty mules, four abreast in the swing, the leaders and wheelers being single teams. For mutual protection trains were made up of from ten to twenty wagons. Drivers frequently meeting a chance acquaintance going in an opposite direction would ask, "What is your cargo?" and the answer would be frankly given, "Specie." Many a Chihuahua wagon carried three or four tons of gold and silver, generally the latter. Here was a new book for this college lad, one he had never studied, though it was more interesting to him than some he had read. There was something thrilling in all this new life. He liked it. The romance was real; it was not an imitation. People answered his few questions and asked none in return.

In this frontier village at a late hour one night young Wells overheard this conversation: "Hello, Bill," said the case-keeper in a faro game, as he turned his head halfway round to see who was the owner of the monster hand which had just reached over his shoulder and placed a stack of silver dollars on a card, marking it to win, "I've missed you the last few days. Where have you been so long?"

"Oh, I've just been out to El Paso on a little pasear guarding the stage," was the reply. Now the little pasear was a continuous night and day round-trip of twelve hundred miles. Bill had slept and eaten as he could. When mounted, he scouted every possible point of ambush for lurking Indian or bandit. Crossing open stretches of country, he climbed up on the stage and slept. Now having returned, he was anxious to get his wages into circulation. Here were characters worthy of a passing glance.

Interesting as this frontier life was to the young man, he prepared for his final destination. He had no trouble in locating his father's property, for it was less than twenty miles from San Antonio. Securing an American who spoke Spanish, the two set out on horseback. There were several small ranchitos on the tract, where five or six Mexican families lived. Each family had a field and raised corn for bread. A flock of goats furnished them milk and meat. The same class of people in older States were called squatters, making no claim to ownership of the land. They needed little clothing, the climate being in their favor.

The men worked at times. The pecan crop which grew along the creek bottoms was beginning to have a value in the coast towns for shipment to northern markets, and this furnished them revenue for their simple needs. All kinds of game was in abundance, including waterfowl in winter, though winter here was only such in name. These simple people gave a welcome to the New Yorker which appeared sincere. They offered no apology for their presence on this land, nor was such in order, for it was the custom of the country. They merely referred to themselves as "his people," as though belonging to the land.

When they learned that he was the son of the owner of the grant, and that he wanted to spend a few months hunting and looking about, they considered themselves honored. The best jacal in the group was tendered him and his interpreter. The food offered was something new, but the relish with which his companion partook of it assisted young Wells in overcoming his scruples, and he ate a supper of dishes he had never tasted before. The coffee he declared was delicious.

On the advice of his companion they had brought along blankets. The women of the ranchito brought other bedding, and a comfortable bed soon awaited the Americanos. The owner of the jacal in the mean time informed his guest through the interpreter that he had sent to a near-by ranchito for a man who had at least the local reputation of being quite a hunter. During the interim, while awaiting the arrival of the man, he plied his guest with many questions regarding the outside world, of which his ideas were very simple, vague, and extremely provincial. His conception of distance was what he could ride in a given number of days on a good pony. His ideas of wealth were no improvement over those of his Indian ancestors of a century previous. In architecture, the jacal in which they sat satisfied his ideals.

The footsteps of a horse interrupted their conversation. A few moments later, Tiburcio, the hunter, was introduced to the two Americans with a profusion of politeness. There was nothing above the ordinary in the old hunter, except his hair, eyes, and swarthy complexion, which indicated his Aztec ancestry. It might be in perfect order to remark here that young Wells was perfectly composed, almost indifferent to the company and surroundings. He shook hands with Tiburcio in a manner as dignified, yet agreeable, as though he was the governor of his native State or the minister of some prominent church at home. From this juncture, he at once took the lead in the conversation, and kept up a line of questions, the answers to which were very gratifying. He learned that deer were very plentiful everywhere, and that on this very tract of land were several wild turkey roosts, where it was no trouble to bag any number desired. On the prairie portion of the surrounding country could be found large droves of antelope. During drouthy periods they were known to come twenty miles to quench their thirst in the Salado, which was the main watercourse of this grant. Once Tiburcio assured his young patron that he had frequently counted a thousand antelope during a single morning. Then there was also the javeline or peccary which abounded in endless numbers, but it was necessary to hunt them with dogs, as they kept the thickets and came out in the open only at night. Many a native cur met his end hunting these animals, cut to pieces with their tusks, so that packs, trained for the purpose, were used to bay them until the hunter could arrive and dispatch them with a rifle. Even this was always done from horseback, as it was dangerous to approach the javeline, for they would, when aroused, charge anything.

All this was gratifying to young Wells, and like a congenial fellow, he produced and showed the old hunter a new gun, the very latest model in the market, explaining its good qualities through his interpreter. Tiburcio handled it as if it were a rare bit of millinery, but managed to ask its price and a few other questions. Through his companion, Wells then engaged the old hunter's services for the following day; not that he expected to hunt, but he wanted to acquaint himself with the boundaries of the land and to become familiar with the surrounding country. Naming an hour for starting in the morning, the two men shook hands and bade each other good-night, each using his own language to express the parting, though neither one knew a word the other said. The first link in a friendship not soon to be broken had been forged.

Tiburcio was on hand at the appointed hour in the morning, and being joined by the two Americans th

ey rode off up the stream. It was October, and the pecans, they noticed, were already falling, as they passed through splendid groves of this timber, several times dismounting to fill their pockets with nuts. Tiburcio frequently called attention to fresh deer tracks near the creek bottom, and shortly afterward the first game of the day was sighted. Five or six does and grown fawns broke cover and ran a short distance, stopped, looked at the horsemen, and then capered away.

Riding to the highest ground in the vicinity, they obtained a splendid view of the stream, outlined by the foliage of the pecan groves that lined its banks as far as the eye could follow either way. Tiburcio pointed out one particular grove lying three or four miles farther up the creek. Here he said was a cabin which had been built by a white man who had left it several years ago, and which he had often used as a hunting camp in bad weather. Feeling his way cautiously, Wells asked the old hunter if he were sure that this cabin was on and belonged to the grant. Being assured on both points, he then inquired if there was anything to hinder him from occupying the hut for a few months. On the further assurance that there was no man to dispute his right, he began plying his companions with questions. The interpreter told him that it was a very common and simple thing for men to batch, enumerating the few articles he would need for this purpose.

They soon reached the cabin, which proved to be an improvement over the ordinary jacal of the country, as it had a fireplace and chimney. It was built of logs; the crevices were chinked with clay for mortar, its floor being of the same substance. The only Mexican feature it possessed was the thatched roof. While the Americans were examining it and its surroundings, Tiburcio unsaddled the horses, picketing one and hobbling the other two, kindled a fire, and prepared a lunch from some articles he had brought along. The meal, consisting of coffee, chipped venison, and a thin wafer bread made from corn and reheated over coals, was disposed of with relish. The two Americans sauntered around for some distance, and on their return to the cabin found Tiburcio enjoying his siesta under a near-by pecan tree.

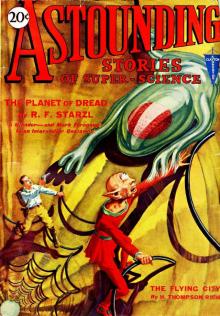

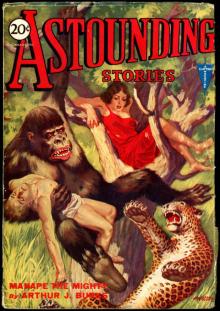

Astounding Stories, March, 1931

Astounding Stories, March, 1931 Astounding Stories, February, 1931

Astounding Stories, February, 1931 Futuria Fantasia, Spring 1940

Futuria Fantasia, Spring 1940 The King's Daughter and Other Stories for Girls

The King's Daughter and Other Stories for Girls Uncanny Tales

Uncanny Tales Masters of Noir: Volume Two

Masters of Noir: Volume Two Witty Pieces by Witty People

Witty Pieces by Witty People Sylvaneth

Sylvaneth Space Wolves

Space Wolves Hammerhal & Other Stories

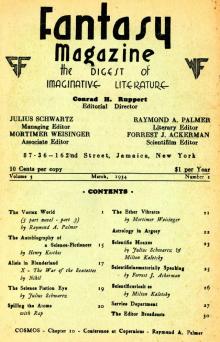

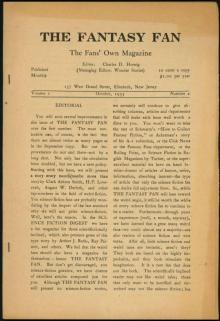

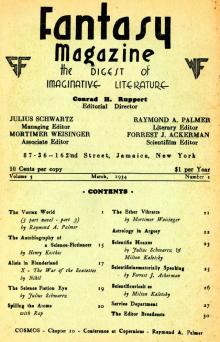

Hammerhal & Other Stories The Fantasy Fan, March, 1934

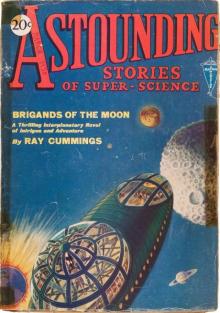

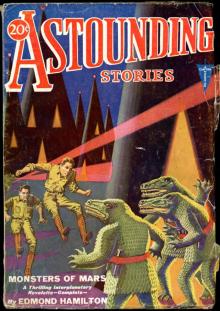

The Fantasy Fan, March, 1934 Astounding Stories of Super-Science, August 1930

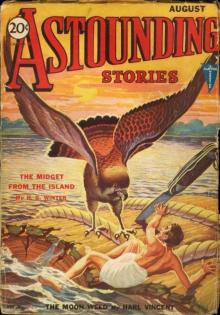

Astounding Stories of Super-Science, August 1930 Astounding Stories, August, 1931

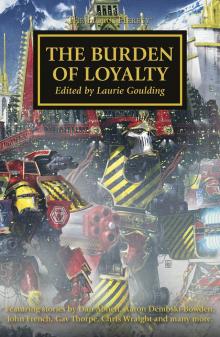

Astounding Stories, August, 1931 The Burden of Loyalty

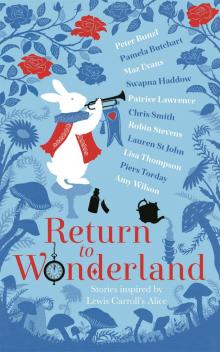

The Burden of Loyalty Return to Wonderland

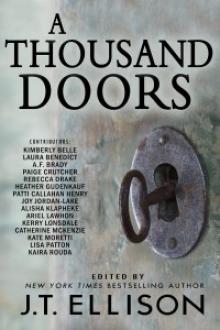

Return to Wonderland Anthology - A Thousand Doors

Anthology - A Thousand Doors The Fantasy Fan, October 1933

The Fantasy Fan, October 1933 Astounding Stories, June, 1931

Astounding Stories, June, 1931 Southern Stories

Southern Stories Astounding Stories of Super-Science, May, 1930

Astounding Stories of Super-Science, May, 1930 The Fantasy Fan December 1933

The Fantasy Fan December 1933 Adventures in Many Lands

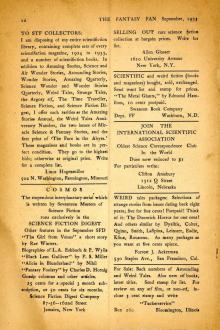

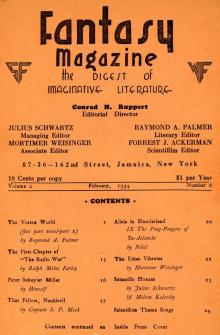

Adventures in Many Lands The Fantasy Fan February 1934

The Fantasy Fan February 1934 The Fantasy Fan November 1933

The Fantasy Fan November 1933 Astounding Stories, April, 1931

Astounding Stories, April, 1931 Fame and Fortune Weekly, No. 801, February 4, 1921

Fame and Fortune Weekly, No. 801, February 4, 1921 Astounding Stories of Super-Science, November, 1930

Astounding Stories of Super-Science, November, 1930 Astounding Stories of Super-Science January 1931

Astounding Stories of Super-Science January 1931 A Monk of Fife

A Monk of Fife Astounding Stories of Super-Science September 1930

Astounding Stories of Super-Science September 1930 Astounding Stories of Super-Science July 1930

Astounding Stories of Super-Science July 1930 Astounding Stories of Super-Science, June, 1930

Astounding Stories of Super-Science, June, 1930 Astounding Stories of Super-Science, October, 1930

Astounding Stories of Super-Science, October, 1930 Astounding Stories of Super-Science, March 1930

Astounding Stories of Super-Science, March 1930 The Fantasy Fan January 1934

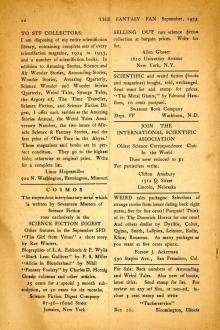

The Fantasy Fan January 1934 The Fantasy Fan September 1933

The Fantasy Fan September 1933 Astounding Stories of Super-Science February 1930

Astounding Stories of Super-Science February 1930 Astounding Stories, May, 1931

Astounding Stories, May, 1931 Strange Stories of Colonial Days

Strange Stories of Colonial Days Golden Age of Science Fiction Vol IX

Golden Age of Science Fiction Vol IX Astounding Stories of Super-Science, December 1930

Astounding Stories of Super-Science, December 1930 Evolutions: Essential Tales of the Halo Universe

Evolutions: Essential Tales of the Halo Universe Good Stories Reprinted from the Ladies' Home Journal of Philadelphia

Good Stories Reprinted from the Ladies' Home Journal of Philadelphia Dragons!

Dragons! Murder Takes a Holiday

Murder Takes a Holiday Legacies of Betrayal

Legacies of Betrayal STAR WARS: TALES FROM THE CLONE WARS

STAR WARS: TALES FROM THE CLONE WARS Strange New Worlds 2016

Strange New Worlds 2016 Lippincott's Magazine, August, 1885

Lippincott's Magazine, August, 1885 Golden Age of Science Fiction Vol X

Golden Age of Science Fiction Vol X Hot Stuff

Hot Stuff Santa Wore Spurs

Santa Wore Spurs Paranormal Erotica

Paranormal Erotica Tangled Hearts: A Menage Collection

Tangled Hearts: A Menage Collection Sweet Tea and Jesus Shoes

Sweet Tea and Jesus Shoes The Journey Prize Stories 25

The Journey Prize Stories 25 Wild Western Tales 2: 101 Classic Western Stories Vol. 2 (Civitas Library Classics)

Wild Western Tales 2: 101 Classic Western Stories Vol. 2 (Civitas Library Classics) (5/15) The Golden Age of Science Fiction Volume V: An Anthology of 50 Short Stories

(5/15) The Golden Age of Science Fiction Volume V: An Anthology of 50 Short Stories (4/15) The Golden Age of Science Fiction Volume IV: An Anthology of 50 Short Stories

(4/15) The Golden Age of Science Fiction Volume IV: An Anthology of 50 Short Stories Ten Journeys

Ten Journeys The Boss

The Boss The Penguin Book of French Poetry

The Penguin Book of French Poetry Golden Age of Science Fiction Vol VIII

Golden Age of Science Fiction Vol VIII His Cinderella Housekeeper 3-in-1

His Cinderella Housekeeper 3-in-1 The Magazine of Fantasy & Science Fiction - July/August 2016

The Magazine of Fantasy & Science Fiction - July/August 2016 PYRATE CTHULHU - Tales of the Cthulhu Mythos (vol.2)

PYRATE CTHULHU - Tales of the Cthulhu Mythos (vol.2) Tales from a Master's Notebook

Tales from a Master's Notebook April 1930

April 1930 New Erotica 6

New Erotica 6 Damocles

Damocles The Longest Night Vol. 1

The Longest Night Vol. 1 The Golden Age of Science Fiction Volume VI: An Anthology of 50 Short Stories

The Golden Age of Science Fiction Volume VI: An Anthology of 50 Short Stories (1/15) The Golden Age of Science Fiction: An Anthology of 50 Short Stories

(1/15) The Golden Age of Science Fiction: An Anthology of 50 Short Stories Eye of Terra

Eye of Terra ONCE UPON A REGENCY CHRISTMAS

ONCE UPON A REGENCY CHRISTMAS Nexus Confessions

Nexus Confessions Passionate Kisses

Passionate Kisses War Without End

War Without End Doctor Who: Time Lord Fairy Tales

Doctor Who: Time Lord Fairy Tales Gotrek and Felix: The Anthology

Gotrek and Felix: The Anthology WESTERN CHRISTMAS PROPOSALS

WESTERN CHRISTMAS PROPOSALS The Journey Prize Stories 27

The Journey Prize Stories 27 The Silent War

The Silent War Liaisons

Liaisons Ellora's Cavemen: Tales from the Temple IV

Ellora's Cavemen: Tales from the Temple IV Ellora's Cavemen: Tales from the Temple II

Ellora's Cavemen: Tales from the Temple II Some of the Best From Tor.com, 2013 Edition: A Tor.Com Original

Some of the Best From Tor.com, 2013 Edition: A Tor.Com Original Urban Occult

Urban Occult Fractures

Fractures The Stories: Five Years of Original Fiction on Tor.com

The Stories: Five Years of Original Fiction on Tor.com The Penguin Book of Modern British Short Stories

The Penguin Book of Modern British Short Stories Mortarch of Night

Mortarch of Night The Portable Nineteenth-Century African American Women Writers

The Portable Nineteenth-Century African American Women Writers The Golden Age of Science Fiction Volume VII: An Anthology of 50 Short Stories

The Golden Age of Science Fiction Volume VII: An Anthology of 50 Short Stories Holy Bible: King James Version, The

Holy Bible: King James Version, The Eight Rooms

Eight Rooms sanguineangels

sanguineangels DarkNightsWithaBillionaireBundle

DarkNightsWithaBillionaireBundle Casserole Diplomacy and Other Stories

Casserole Diplomacy and Other Stories How I Survived My Summer Vacation

How I Survived My Summer Vacation Alfred Hitchcock Presents: 16 Skeletons From My Closet

Alfred Hitchcock Presents: 16 Skeletons From My Closet Lords, Ladies, Butlers and Maids

Lords, Ladies, Butlers and Maids The B4 Leg

The B4 Leg Ellora's Cavemen: Tales from the Temple I

Ellora's Cavemen: Tales from the Temple I 2014 Campbellian Anthology

2014 Campbellian Anthology There Is Only War

There Is Only War Obsidian Alliances

Obsidian Alliances 12 Gifts for Christmas

12 Gifts for Christmas Scary Holiday Tales to Make You Scream

Scary Holiday Tales to Make You Scream 25 For 25

25 For 25 The Plagues of Orath

The Plagues of Orath And Then He Kissed Me

And Then He Kissed Me Star Trek - Gateways 7 - WHAT LAY BEYOND

Star Trek - Gateways 7 - WHAT LAY BEYOND Laugh Your Head Off Again and Again

Laugh Your Head Off Again and Again The Balfour Legacy

The Balfour Legacy Golden Age of Science Fiction Vol XI

Golden Age of Science Fiction Vol XI (3/15) The Golden Age of Science Fiction Volume III: An Anthology of 50 Short Stories

(3/15) The Golden Age of Science Fiction Volume III: An Anthology of 50 Short Stories Shas'o

Shas'o Astounding Science Fiction Stories: An Anthology of 350 Scifi Stories Volume 2 (Halcyon Classics)

Astounding Science Fiction Stories: An Anthology of 350 Scifi Stories Volume 2 (Halcyon Classics) Twists in Time

Twists in Time Meduson

Meduson The Magazine of Fantasy & Science Fiction - August 1980

The Magazine of Fantasy & Science Fiction - August 1980 The Journey Prize Stories 22

The Journey Prize Stories 22 The Book that Made Me

The Book that Made Me Angels of Death Anthology

Angels of Death Anthology Ask the Bones

Ask the Bones Emergence

Emergence Beware the Little White Rabbit

Beware the Little White Rabbit Xcite Delights Book 1

Xcite Delights Book 1 Where flap the tatters of the King

Where flap the tatters of the King The Journey Prize Stories 21

The Journey Prize Stories 21 Tales of the Slayer, Volume II

Tales of the Slayer, Volume II Glass Empires

Glass Empires Golden Age of Science Fiction Vol XII

Golden Age of Science Fiction Vol XII (2/15) The Golden Age of Science Fiction Volume II: An Anthology of 50 Short Stories

(2/15) The Golden Age of Science Fiction Volume II: An Anthology of 50 Short Stories Fairytale Collection

Fairytale Collection Angels!

Angels! Golden Age of Science Fiction Vol XIII

Golden Age of Science Fiction Vol XIII