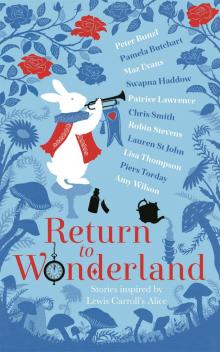

Return to Wonderland Read online

Contents

Acorns, Biscuits and Treacle

by Peter Bunzl

The Queen of Hearts and the Unwritten Written Rule

by Pamela Butchart

The Sensible Hatter

by Maz Evans

The Missing Book

by Swapna Haddow

Roll of Honour

by Patrice Lawrence

The Tweedle Twins and the Case of the Colossal Crow

by Chris Smith

Ina Out of Wonderland

by Robin Stevens

Plum Cakes at Dawn

by Lauren St John

The Knave of Hearts

by Lisa Thompson

How the Cheshire Cat Got His Smile

by Piers Torday

The Caterpillar and the Moth Rumour

by Amy Wilson

About the Authors

Copyright

Acorns, Biscuits and Treacle

by Peter Bunzl

Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland was among my favourite books as a kid. It influenced one of my first stories, written aged ten, about a boy stranded on a desert island who, like Alice, encounters multiple magical creatures before he’s finally able to find his way home. My dad kept that early effort for years. When he returned it to me recently, I realised it contained similar themes to this tale: a shape-shifting hero, a dollop of magic and a handful of Lewis Carroll’s characters, repurposed for a new adventure. My ten-year-old self would be so proud to see my forty-three-year-old self’s short Wonderland story in print. I hope you enjoy ‘Acorns, Biscuits and Treacle’ as much as we do!

Peter Bunzl

One morning, Pig woke to discover he had been turned into a real boy.

Of course, it wasn’t obvious at first to Pig that he’d become a real boy because, in many ways, pigs and boys are quite similar. His body was still the same shade of pink it had always been, and he was still splattered in the same brown splotches of mud he rolled in every day to keep the hot sun from crackling his skin.

It was only when he tried to stand from where he’d laid his head, in a patch of shade beneath an old fig tree, that Pig first noticed something was amiss. For he found he could not get up on all fours in the usual way, as each of his joints had moved about on his body, and where his trotters used to be were two flat hands with long thin fingers that looked like – and Pig hated to use this word – sausages.

For a moment, Pig wondered if he was still dreaming.

In his last dream, he’d been sniffing around in his favourite oak grove, beneath a crescent moon as wide as the grinning Cheshire Cat, searching for acorns. Instead, he’d found an open tin of twelve delicious-looking iced biscuits, each with pink writing on that Pig couldn’t read.

Naturally he’d snuffled the whole box.

Pig flexed his knuckles and found that his new fingers were quite sensitive and moved easily. He could feel every lump and bump on the ground with them.

He put a hand up to his face and felt about to see if that had changed too.

It had.

His ears had got smaller and now stuck out from the sides of his head, and where they had previously been, on the very top of his bald patch, he now had a thick thatch of hair, scruffy as a hay stack.

Curiouser and curiouser.

Where his large flat nose had formerly sat, taking up all his view, he now found a meagre round blob. Though when he felt that new nose, it turned out to be as snub as the old one. Pig picked at the holes in it with a finger, and that felt good.

Pig looked down at his hind legs. They had grown longer and thicker and now ended in big flat rectangular lumps – feet with toes that wiggled when he concentrated on them. He found having toes a pleasant change from trotters. Somewhere, in a far-off memory, Pig had heard a children’s nursery rhyme that called fingers and toes ‘piggies’. It seemed an odd name for them.

Gradually he was acclimatizing to his new body. So much so that he thought he would try standing up.

He climbed slowly on to his two long legs and pushed himself off from the ground.

For a few seconds, he wobbled like a newborn runt; then his knees buckled under him, and his legs gave way, and he fell over backwards.

It hurt quite badly, and Pig decided that walking on two legs was going to be more difficult than he had imagined. As far as he could tell, standing up like a human just meant you had further to fall.

He tried again. This time, things went better as he remembered he had arms and threw them out to balance himself, placing one palm on the rough bark of the tree to keep upright.

Then he discovered he could hold on to a branch with his new grasp-y fingers, and that helped him stay on his feet even longer.

Pig looked at the ground far below and felt pretty pleased with himself. Now he was standing like a real human boy, he thought he might perhaps give walking a go.

He picked up one of his big flat feet, tipped himself forward, and promptly fell over again. Flat on his face.

It took Pig a good part of the morning to learn how to walk upright on his hind legs – or his only legs, really, since the other two were arms now. He didn’t know if his progress was quick or not, but it felt an immensely long time to him. Walking like this, Pig began to feel more human. Now that he was human, he wondered if he should change his name.

The trouble was he liked the name Pig. A kindly sow had given it to him when she’d adopted him. Not that it was unique; it was what the herd called everyone. Everyone except the littlest hogs, whom they christened Piglet, Runt or Oinker.

Names hadn’t mattered to Pig back then, but one day he’d wandered off and got separated from the herd and hadn’t known how to call them back.

Perhaps he should refer to himself as Boy, now that he was one. Maybe he could combine both names, and put the second one after the first, like humans did: Pig Boy.

Yes. That sounded good.

In the back of Pig’s mind, he vaguely recalled being human once before, a long time ago. A smaller, tiny human. That’s where the nursery-rhyme memory had come from. He’d had a mother who’d sung it to him, roughly. She might even have called him Pig – he had a hazy remembrance of that too.

Pig thought these things as he walked along, and the wind blew around his skin, giving him goose bumps and making him shiver with cold. This, he surmised, was probably the reason – or was the word raisin? – that humans wore clothes. He’d need an outfit anyway if he were to venture forth from the woods and not make everyone he encountered run away in shock at his muddy nakedness.

Pig wondered where he could possibly find clothes to fit him, since he lived deep in the wilds, far from any human settlements. But surely, he thought, if he just kept walking, chances were he’d eventually stumble across something that was good enough to wear.

Some time later, after Pig had been meandering aimlessly for a good few hours without a plan, he came upon a clearing in the woods.

In the centre of the clearing was a stone well. Beside it, Pig noticed a few items of clothing strewn about: a woollen shawl, a long coat, a dainty pair of shoes and a big floppy straw hat.

Next to these was a bucket on a rope fixed to a winch above the well.

Pig approached the bucket and was surprised to find it full of an unctuous amber-coloured liquid. He dipped a finger in and tasted it. Delicious! Sticky, sweet and syrupy, like . . . treacle.

Pig was so hungry by this point that he scooped up big handfuls of the treacle and ate it as fast as he could. Then, since he couldn’t see anyone around to whom the clothes might belong, he crouched down beside them and began putting them on.

First, he tied the shawl around his waist like a skirt; next, he climbed into the long coat. It took him a while to fi

gure out which way up it went and whether the long skinny bits were for arms or legs, but when he finally got it on right, he buttoned it closed over his chest.

Last, he put the straw hat on top of his head, over his straw-like hair. It turned out its floppy edges excelled at shading his new side-ears from the sun.

Pig considered trying on the shoes too, even though they looked a bit on the small side and were so black and shiny, they would probably make his feet look like trotters again. He was about to attempt to push his feet into them when he heard a shout.

‘HELP!’ three voices yelled, reverberating around him.

Pig realized they were coming from down the well.

He peered cautiously over its edge, and there – on a ledge in the half-light, near the bottom of the well – were three well-dressed young ladies.

‘Help us, please!’ they cried again in unison.

For some reason, Pig understood them perfectly well. He opened his mouth to reply, but since he had never spoken words before only grunts came out.

‘HGGOR GNRR,’ he said, and wasn’t even sure himself what that meant.

‘Throw down the bucket,’ the tallest of the three girls said. ‘So we can climb out.’

‘HHOORRHGGH,’ Pig said, and he threw the bucket into the well, winching it down on the rope to the three girls below.

The girls argued for some time about who should be rescued first. Finally, it was decided that the lightest and smallest of them should go.

So the littlest girl, who looked about ten years old, got into the bucket and tugged twice on the rope, and Pig wound the winch handle and pulled her up.

‘Thank heavens!’ she cried when she finally reached the top. ‘You saved our bacon!’

She climbed over the parapet and fell against the wall’s sticky stone buttress. Pig thought she looked jolly odd up close, for she was covered from head to toe in treacle. It must, he concluded, be a treacle well.

‘Ugh,’ said the smallest girl with a shiver. ‘I feel quite ill.’

She took a few deep breaths, and then, when she was fully recovered, looked seriously at Pig.

‘You’re wearing our clothes.’

‘I found them on the ground,’ Pig replied. ‘They fit rather well.’

He put his hand to his mouth in shock for the words had come unbidden. He hadn’t intended to answer the girl in her own language, just like that.

‘So you do speak,’ the smallest girl said. ‘My name’s Tillie. What’s yours?’

‘Pig,’ said Pig, shortly. He left off the Boy part as he hadn’t quite decided on that yet.

Tillie eyed him suspiciously. ‘Pig’s a queer sort of name, especially for a boy wearing girls’ clothes.’

‘And Tillie’s a curious sort of name for a girl covered in treacle who lives down the bottom of a well,’ Pig replied indignantly.

Tillie tried to wipe the offending treacle from the arms of her dress, but it only smeared into the material and made things worse. ‘It’s very uncivil to comment on another person’s appearance,’ she said. ‘And, anyway, I think you may have misconstrued our situation. We do not live down the bottom of a well. We fell down it. We live, in fact, in a house on the edge of the woods. We were merely sent here by our mother to get some treacle for the treacle tarts she wanted to make for the Queen of Hearts’s annual croquet party—’

Here she was interrupted by the other two girls, whom Pig had entirely forgotten about, and who were still waiting to be rescued from the well themselves.

‘I say, up there – throw down the rope!’ they demanded.

Tillie’s eyes went wide with shock. ‘Good heavens!’ she exclaimed. ‘My sisters! They slipped my mind! I do tend to be a tad loquacious when I get going.’

She stood up, and she and Pig lowered the bucket again, and together they hauled up the middle-sized sister.

The middle-sized sister turned out to be called Elsie.

Then the three of them hauled up the biggest sister, whose name was revealed to be Lacie.

All three sisters stood in a line in order of size and tried to brush the treacle off one another, but this only made them stickier. Pig saw that Elsie was missing her shawl, Lacie her hat, and Tillie her coat, and realized that he was sporting an item belonging to each of them.

When they finally noticed he was wearing their clothes, the two other sisters looked taken aback. Nonetheless, they didn’t ask for their things back.

Tillie picked up her shoes and tried to put them on, but immediately treacle began seeping out of their sides, so she tied the laces together and hung them round her neck.

She would walk barefoot through the forest like Pig, she decided.

‘We should be off home,’ said Lacie. ‘Our mother will be wondering what’s kept us.’

The three of them untied the treacle bucket from the rope and set off with it out of the clearing. As they walked, they took turns to carefully carry the bucket so no treacle slopped over the sides. Lacie did most of the carrying because she was the eldest, and because the other two proclaimed themselves thoroughly sick of treacle.

Pig went along with them since he had nowhere else in particular he had to be.

‘Who is your mother?’ he asked, following the three treacle-dripping girls along a narrow path through the woods that they were navigating with some familiarity.

‘Why, she is the cook to the Duchess, of course,’ said Tillie. ‘The whole of Wonderland knows that.’

‘The Duchess?’ said Pig, for that name sounded familiar.

‘Yes,’ said Elsie. ‘Three-hundred-and-sixty-six days ago, the Duchess told our mother to bake some tarts for the Queen of Hearts so she could take them to her annual game of croquet.’

‘So Mummy sent us out to get the treacle from the well,’ Lacie continued, ‘only . . . well, the three of us ate so much of it when we arrived that we got a touch overexcited and decided to have a Caucus race.’

‘What’s a Caucus Race?’ Pig asked. He’d been gathering acorns from the side of the path and snuffling at them with his nose while they spoke. Even though he was a boy now, he couldn’t help himself, for there were so many tasty-looking ones strewn about.

‘A Caucus race is a race in a circle,’ Elsie explained. ‘In this case, round the well. It starts when you want to begin and finishes when you want to stop.’

‘And while we were doing that,’ Tillie added, continuing with the story, ‘we each of us slipped on a separate patch of treacle and fell down the well.’

‘We were hoping it might be the gateway to somewhere,’ Elsie said. ‘To another world that was a trifle less curious than this one. But, no – it just turned out to be a plain old treacle well.’

‘So we were stuck down there for a year and a day, living on treacle, which is no better than trifle, really,’ Lacie said. ‘And with no one to rescue us. Until you came along.’

Pig gave a grunt of sympathy. ‘I’m sorry to hear that,’ he said.

‘Where do you come from, exactly?’ Elsie asked.

‘And why do you act so funny?’ Tillie added.

‘I’m not entirely sure,’ Pig replied. ‘Last night, when I went to sleep beneath my favourite fig tree, I was a wild pig. I dreamed of eating a tin of biscuits in an oak grove . . . and this morning, when I woke, I had turned into a real boy. The funny thing is, now that I am a real boy, I recall being one before – a boy who was a lot . . . smaller. A tiny baby, in fact. As for why I act so funny, well . . . I’m trying my best to do boyish things, but the truth is I’m still slightly piggy inside.’

Pig told this whole tale quite fluently, and was mystified to find he had no trouble getting so many human words out. Once he had finished, he looked up to find that the four of them had arrived at the edge of the woods.

There, beyond the last few trees, behind a low picket fence, stood a cosy-looking cottage that looked awfully familiar, with ivy and roses winding round the door, and a thatched roof that was barely higher than he was.

On the cottage doorstep sat a Frog-Footman in a powdered periwig and a dress coat. He had his hands over his face and was sobbing profusely. ‘Tillie, Lacie, Elsie!’ he called out in surprise when he looked up and saw the three girls approaching. ‘Do my sore eyes deceive me? How terribly late you are back for your supper! Tragically late!’

‘Why?’ Tillie asked. ‘What’s happened, Froggy, dear?’

‘Countless awful things!’ The Frog-Footman wiped his cheeks with a corner of his wig. ‘Three days after you vanished, the Duchess gave her son – her baby boy – to a strange girl called Alice who was passing through, and he turned into a piglet right there in her arms, wiggled free and ran off into the woods! Afterwards, the Duchess declared she didn’t care for such naughty babies. And the cook said she didn’t either, not for the lost child, nor for the girl called Alice, nor for you, her own three missing daughters. Then the pair of them put on their glad rags and went off together to play croquet with the Queen of Hearts. The tournament went on for a week, and when they beat the Queen at her own game she shouted, “Off with their heads!” and it was done. I’ve been sitting here crying about it ever since.’

‘How awful!’ exclaimed Elsie.

Pig didn’t know if she was referring to the fact that her mother and the Duchess had gone off gaily to play croquet despite their missing children, or the news that the pair of them had had their heads cut off, or the revelation that the Frog-Footman had been sitting on the front step crying for nearly a year and day.

‘She was a terrible mother,’ Elsie said.

‘And a terrible cook,’ Tillie added.

‘She spoke most roughly to us and scolded us when we sneezed,’ Lacie said. ‘Which was relatively often, on account of the pepper she used on everything, even the laundry.’

‘The Duchess was quite unpleasant too,’ Elsie said. ‘Remember the curses she threw at her baby. And the plates?’

‘And what kind of woman gives her infant away to the first wandering stranger who passes through?’ Tillie said.

‘And to call her son Pig in the first place,’ Lacie added. ‘If that’s not enough to set wild magic in motion, I don’t know what is! No wonder he turned into a piglet!’

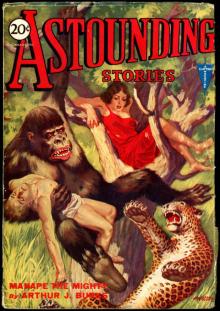

Astounding Stories, March, 1931

Astounding Stories, March, 1931 Astounding Stories, February, 1931

Astounding Stories, February, 1931 Futuria Fantasia, Spring 1940

Futuria Fantasia, Spring 1940 The King's Daughter and Other Stories for Girls

The King's Daughter and Other Stories for Girls Uncanny Tales

Uncanny Tales Masters of Noir: Volume Two

Masters of Noir: Volume Two Witty Pieces by Witty People

Witty Pieces by Witty People Sylvaneth

Sylvaneth Space Wolves

Space Wolves Hammerhal & Other Stories

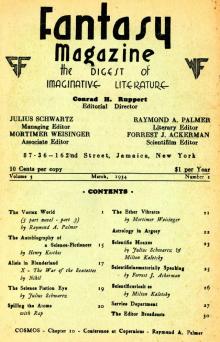

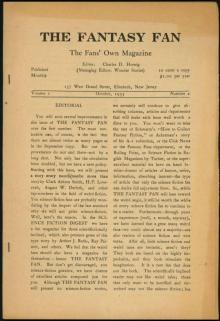

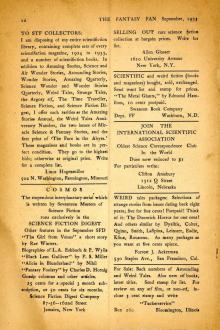

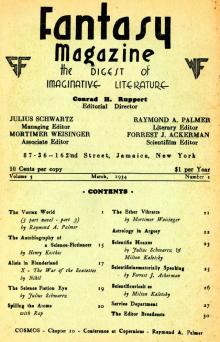

Hammerhal & Other Stories The Fantasy Fan, March, 1934

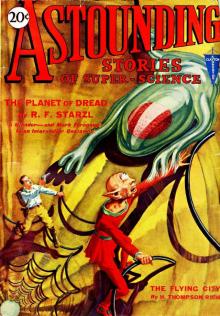

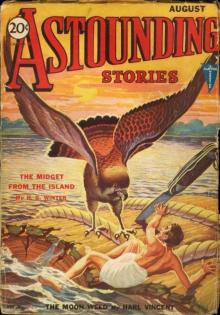

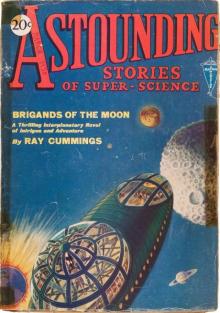

The Fantasy Fan, March, 1934 Astounding Stories of Super-Science, August 1930

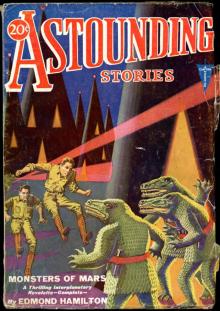

Astounding Stories of Super-Science, August 1930 Astounding Stories, August, 1931

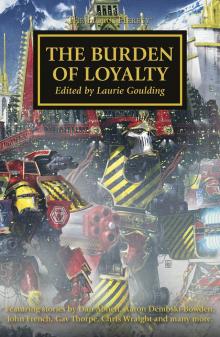

Astounding Stories, August, 1931 The Burden of Loyalty

The Burden of Loyalty Return to Wonderland

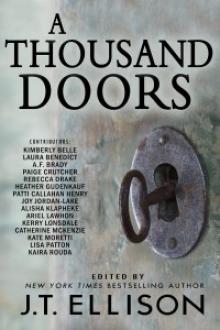

Return to Wonderland Anthology - A Thousand Doors

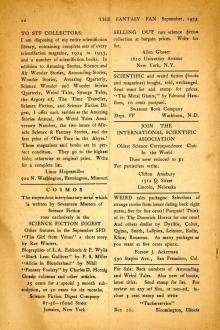

Anthology - A Thousand Doors The Fantasy Fan, October 1933

The Fantasy Fan, October 1933 Astounding Stories, June, 1931

Astounding Stories, June, 1931 Southern Stories

Southern Stories Astounding Stories of Super-Science, May, 1930

Astounding Stories of Super-Science, May, 1930 The Fantasy Fan December 1933

The Fantasy Fan December 1933 Adventures in Many Lands

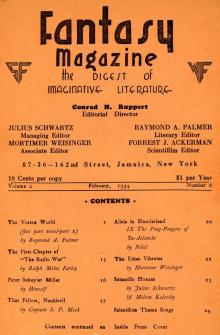

Adventures in Many Lands The Fantasy Fan February 1934

The Fantasy Fan February 1934 The Fantasy Fan November 1933

The Fantasy Fan November 1933 Astounding Stories, April, 1931

Astounding Stories, April, 1931 Fame and Fortune Weekly, No. 801, February 4, 1921

Fame and Fortune Weekly, No. 801, February 4, 1921 Astounding Stories of Super-Science, November, 1930

Astounding Stories of Super-Science, November, 1930 Astounding Stories of Super-Science January 1931

Astounding Stories of Super-Science January 1931 A Monk of Fife

A Monk of Fife Astounding Stories of Super-Science September 1930

Astounding Stories of Super-Science September 1930 Astounding Stories of Super-Science July 1930

Astounding Stories of Super-Science July 1930 Astounding Stories of Super-Science, June, 1930

Astounding Stories of Super-Science, June, 1930 Astounding Stories of Super-Science, October, 1930

Astounding Stories of Super-Science, October, 1930 Astounding Stories of Super-Science, March 1930

Astounding Stories of Super-Science, March 1930 The Fantasy Fan January 1934

The Fantasy Fan January 1934 The Fantasy Fan September 1933

The Fantasy Fan September 1933 Astounding Stories of Super-Science February 1930

Astounding Stories of Super-Science February 1930 Astounding Stories, May, 1931

Astounding Stories, May, 1931 Strange Stories of Colonial Days

Strange Stories of Colonial Days Golden Age of Science Fiction Vol IX

Golden Age of Science Fiction Vol IX Astounding Stories of Super-Science, December 1930

Astounding Stories of Super-Science, December 1930 Evolutions: Essential Tales of the Halo Universe

Evolutions: Essential Tales of the Halo Universe Good Stories Reprinted from the Ladies' Home Journal of Philadelphia

Good Stories Reprinted from the Ladies' Home Journal of Philadelphia Dragons!

Dragons! Murder Takes a Holiday

Murder Takes a Holiday Legacies of Betrayal

Legacies of Betrayal STAR WARS: TALES FROM THE CLONE WARS

STAR WARS: TALES FROM THE CLONE WARS Strange New Worlds 2016

Strange New Worlds 2016 Lippincott's Magazine, August, 1885

Lippincott's Magazine, August, 1885 Golden Age of Science Fiction Vol X

Golden Age of Science Fiction Vol X Hot Stuff

Hot Stuff Santa Wore Spurs

Santa Wore Spurs Paranormal Erotica

Paranormal Erotica Tangled Hearts: A Menage Collection

Tangled Hearts: A Menage Collection Sweet Tea and Jesus Shoes

Sweet Tea and Jesus Shoes The Journey Prize Stories 25

The Journey Prize Stories 25 Wild Western Tales 2: 101 Classic Western Stories Vol. 2 (Civitas Library Classics)

Wild Western Tales 2: 101 Classic Western Stories Vol. 2 (Civitas Library Classics) (5/15) The Golden Age of Science Fiction Volume V: An Anthology of 50 Short Stories

(5/15) The Golden Age of Science Fiction Volume V: An Anthology of 50 Short Stories (4/15) The Golden Age of Science Fiction Volume IV: An Anthology of 50 Short Stories

(4/15) The Golden Age of Science Fiction Volume IV: An Anthology of 50 Short Stories Ten Journeys

Ten Journeys The Boss

The Boss The Penguin Book of French Poetry

The Penguin Book of French Poetry Golden Age of Science Fiction Vol VIII

Golden Age of Science Fiction Vol VIII His Cinderella Housekeeper 3-in-1

His Cinderella Housekeeper 3-in-1 The Magazine of Fantasy & Science Fiction - July/August 2016

The Magazine of Fantasy & Science Fiction - July/August 2016 PYRATE CTHULHU - Tales of the Cthulhu Mythos (vol.2)

PYRATE CTHULHU - Tales of the Cthulhu Mythos (vol.2) Tales from a Master's Notebook

Tales from a Master's Notebook April 1930

April 1930 New Erotica 6

New Erotica 6 Damocles

Damocles The Longest Night Vol. 1

The Longest Night Vol. 1 The Golden Age of Science Fiction Volume VI: An Anthology of 50 Short Stories

The Golden Age of Science Fiction Volume VI: An Anthology of 50 Short Stories (1/15) The Golden Age of Science Fiction: An Anthology of 50 Short Stories

(1/15) The Golden Age of Science Fiction: An Anthology of 50 Short Stories Eye of Terra

Eye of Terra ONCE UPON A REGENCY CHRISTMAS

ONCE UPON A REGENCY CHRISTMAS Nexus Confessions

Nexus Confessions Passionate Kisses

Passionate Kisses War Without End

War Without End Doctor Who: Time Lord Fairy Tales

Doctor Who: Time Lord Fairy Tales Gotrek and Felix: The Anthology

Gotrek and Felix: The Anthology WESTERN CHRISTMAS PROPOSALS

WESTERN CHRISTMAS PROPOSALS The Journey Prize Stories 27

The Journey Prize Stories 27 The Silent War

The Silent War Liaisons

Liaisons Ellora's Cavemen: Tales from the Temple IV

Ellora's Cavemen: Tales from the Temple IV Ellora's Cavemen: Tales from the Temple II

Ellora's Cavemen: Tales from the Temple II Some of the Best From Tor.com, 2013 Edition: A Tor.Com Original

Some of the Best From Tor.com, 2013 Edition: A Tor.Com Original Urban Occult

Urban Occult Fractures

Fractures The Stories: Five Years of Original Fiction on Tor.com

The Stories: Five Years of Original Fiction on Tor.com The Penguin Book of Modern British Short Stories

The Penguin Book of Modern British Short Stories Mortarch of Night

Mortarch of Night The Portable Nineteenth-Century African American Women Writers

The Portable Nineteenth-Century African American Women Writers The Golden Age of Science Fiction Volume VII: An Anthology of 50 Short Stories

The Golden Age of Science Fiction Volume VII: An Anthology of 50 Short Stories Holy Bible: King James Version, The

Holy Bible: King James Version, The Eight Rooms

Eight Rooms sanguineangels

sanguineangels DarkNightsWithaBillionaireBundle

DarkNightsWithaBillionaireBundle Casserole Diplomacy and Other Stories

Casserole Diplomacy and Other Stories How I Survived My Summer Vacation

How I Survived My Summer Vacation Alfred Hitchcock Presents: 16 Skeletons From My Closet

Alfred Hitchcock Presents: 16 Skeletons From My Closet Lords, Ladies, Butlers and Maids

Lords, Ladies, Butlers and Maids The B4 Leg

The B4 Leg Ellora's Cavemen: Tales from the Temple I

Ellora's Cavemen: Tales from the Temple I 2014 Campbellian Anthology

2014 Campbellian Anthology There Is Only War

There Is Only War Obsidian Alliances

Obsidian Alliances 12 Gifts for Christmas

12 Gifts for Christmas Scary Holiday Tales to Make You Scream

Scary Holiday Tales to Make You Scream 25 For 25

25 For 25 The Plagues of Orath

The Plagues of Orath And Then He Kissed Me

And Then He Kissed Me Star Trek - Gateways 7 - WHAT LAY BEYOND

Star Trek - Gateways 7 - WHAT LAY BEYOND Laugh Your Head Off Again and Again

Laugh Your Head Off Again and Again The Balfour Legacy

The Balfour Legacy Golden Age of Science Fiction Vol XI

Golden Age of Science Fiction Vol XI (3/15) The Golden Age of Science Fiction Volume III: An Anthology of 50 Short Stories

(3/15) The Golden Age of Science Fiction Volume III: An Anthology of 50 Short Stories Shas'o

Shas'o Astounding Science Fiction Stories: An Anthology of 350 Scifi Stories Volume 2 (Halcyon Classics)

Astounding Science Fiction Stories: An Anthology of 350 Scifi Stories Volume 2 (Halcyon Classics) Twists in Time

Twists in Time Meduson

Meduson The Magazine of Fantasy & Science Fiction - August 1980

The Magazine of Fantasy & Science Fiction - August 1980 The Journey Prize Stories 22

The Journey Prize Stories 22 The Book that Made Me

The Book that Made Me Angels of Death Anthology

Angels of Death Anthology Ask the Bones

Ask the Bones Emergence

Emergence Beware the Little White Rabbit

Beware the Little White Rabbit Xcite Delights Book 1

Xcite Delights Book 1 Where flap the tatters of the King

Where flap the tatters of the King The Journey Prize Stories 21

The Journey Prize Stories 21 Tales of the Slayer, Volume II

Tales of the Slayer, Volume II Glass Empires

Glass Empires Golden Age of Science Fiction Vol XII

Golden Age of Science Fiction Vol XII (2/15) The Golden Age of Science Fiction Volume II: An Anthology of 50 Short Stories

(2/15) The Golden Age of Science Fiction Volume II: An Anthology of 50 Short Stories Fairytale Collection

Fairytale Collection Angels!

Angels! Golden Age of Science Fiction Vol XIII

Golden Age of Science Fiction Vol XIII