The Journey Prize Stories 27 Read online

WINNERS OF THE $10,000 JOURNEY PRIZE

1989: Holley Rubinsky for “Rapid Transits”

1990: Cynthia Flood for “My Father Took a Cake to France”

1991: Yann Martel for “The Facts Behind the Helsinki Roccamatios”

1992: Rozena Maart for “No Rosa, No District Six”

1993: Gayla Reid for “Sister Doyle’s Men”

1994: Melissa Hardy for “Long Man the River”

1995: Kathryn Woodward for “Of Marranos and Gilded Angels”

1996: Elyse Gasco for “Can You Wave Bye Bye, Baby?”

1997 (shared): Gabriella Goliger for “Maladies of the Inner Ear” Anne Simpson for “Dreaming Snow”

1998: John Brooke for “The Finer Points of Apples”

1999: Alissa York for “The Back of the Bear’s Mouth”

2000: Timothy Taylor for “Doves of Townsend”

2001: Kevin Armstrong for “The Cane Field”

2002: Jocelyn Brown for “Miss Canada”

2003: Jessica Grant for “My Husband’s Jump”

2004: Devin Krukoff for “The Last Spark”

2005: Matt Shaw for “Matchbook for a Mother’s Hair”

2006: Heather Birrell for “BriannaSusannaAlana”

2007: Craig Boyko for “OZY”

2008: Saleema Nawaz for “My Three Girls”

2009: Yasuko Thanh for “Floating Like the Dead”

2010: Devon Code for “Uncle Oscar”

2011: Miranda Hill for “Petitions to Saint Chronic”

2012: Alex Pugsley for “Crisis on Earth-X”

2013: Naben Ruthnum for “Cinema Rex”

2014: Tyler Keevil for “Sealskin”

Copyright © 2015 by McClelland & Stewart

“Renaude” © Charlotte Bondy; “Last Animal Standing on Gentleman’s Farm” © Emily Bossé; “The Wise Baby” © Deirdre Dore; “Maggie’s Farm” © Charlie Fiset; “Mercy Beatrice Wrestles the Noose” © K’ari Fisher; “Red Egg and Ginger” © Anna Ling Kaye; “The Perfect Man for My Husband” © Andrew MacDonald; “Achilles’ Death” © Madeleine Maillet; “Fingernecklace” © Lori McNulty; “Lovely Company” © Ron Schafrick; “Moonman” © Sarah Meehan Sirk; “Cocoa Divine and the Lightning Police” © Georgia Wilder

All rights reserved. The use of any part of this publication reproduced, transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, or stored in a retrieval system, without the prior written consent of the publisher—or, in case of photocopying or other reprographic copying, a licence from the Canadian Copyright Licensing Agency—is an infringement of the copyright law.

Library and Archives of Canada Cataloguing in Publication is available upon request

The lines quoted and parodied on this page are from the poem “We Real Cool” by Gwendolyn Brooks, from The Bean Eaters by Gwendolyn Brooks.

Published simultaneously in the United States of America by McClelland & Stewart, a division of Random House of Canada Limited

Library of Congress Control Number available upon request

ISBN: 978-0-7710-5061-9

ebook ISBN: 978-0-7710-5062-6

Cover design: Leah Springate

McClelland & Stewart,

a division of Random House of Canada Limited,

a Penguin Random House Company

www.penguinrandomhouse.ca

v3.1

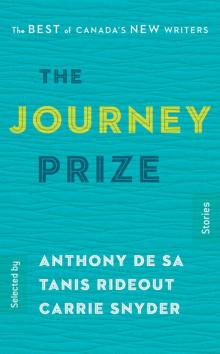

ABOUT THE JOURNEY PRIZE STORIES

The $10,000 Journey Prize is awarded annually to an emerging writer of distinction. This award, now in its twenty-seventh year, and given for the fifteenth time in association with the Writers’ Trust of Canada as the Writers’ Trust of Canada/McClelland & Stewart Journey Prize, is made possible by James A. Michener’s generous donation of his Canadian royalty earnings from his novel Journey, published by McClelland & Stewart in 1988. The Journey Prize itself is the most significant monetary award given in Canada to a developing writer for a short story or excerpt from a fiction work in progress. The winner of this year’s Journey Prize will be selected from among the twelve stories in this book.

The Journey Prize Stories has established itself as the most prestigious annual fiction anthology in the country, introducing readers to the finest new literary writers from coast to coast for more than two decades. It has become a who’s who of up-and-coming writers, and many of the authors who have appeared in the anthology’s pages have gone on to distinguish themselves with short story collections, novels, and literary awards. The anthology comprises a selection from submissions made by the editors of literary journals from across the country, who have chosen what, in their view, is the most exciting writing in English that they have published in the previous year. In recognition of the vital role journals play in fostering literary voices, McClelland & Stewart makes its own award of $2,000 to the journal that originally published and submitted the winning entry.

This year the selection jury comprised three acclaimed writers:

Anthony De Sa is the author of the fiction collection Barnacle Love, a finalist for the Scotiabank Giller Prize and the Toronto Book Award, and the novel Kicking the Sky. He attended the Humber School for Writers and Ryerson University. He lives in Toronto with his wife and three children.

Tanis Rideout is the author of the novel Above All Things and the poetry collection Arguments with the Lake. Her work has been shortlisted for several prizes, including the Bronwen Wallace Memorial Award for Emerging Writers and the CBC Literary Awards. She has an M.F.A. from the University of Guelph. She lives in Toronto, Ontario.

Carrie Snyder is the author of the novel Girl Runner, which was a finalist for the Rogers Writers’ Trust Fiction Prize, as well as two books of short fiction: Hair Hat, a finalist for the Danuta Gleed Award for Short Fiction, and The Juliet Stories, a finalist for the Governor General’s Literary Award. She lives in Waterloo, Ontario.

The jury read a total of ninety-six submissions without knowing the names of the authors or those of the journals in which the stories originally appeared. McClelland & Stewart would like to thank the jury for their efforts in selecting this year’s anthology and, ultimately, the winner of this year’s Journey Prize.

McClelland & Stewart would also like to acknowledge the continuing enthusiastic support of writers, literary journal editors, and the public in the common celebration of new voices in Canadian fiction.

For more information about The Journey Prize Stories, please visit www.facebook.com/TheJourneyPrize.

CONTENTS

Cover

Winners of the $10,000 Journey Prize

Title Page

Copyright

About the Journey Prize Stories

Introduction

Anthony De Sa, Tanis Rideout, and Carrie Snyder

LORI MCNULTY

Fingernecklace

(from PRISM international)

K’ARI FISHER

Mercy Beatrice Wrestles the Noose

(from The Malahat Review)

CHARLOTTE BONDY

Renaude

(from The Impressment Gang)

GEORGIA WILDER

Cocoa Divine and the Lightning Police

(from Descant)

ANDREW MACDONALD

The Perfect Man for My Husband

(from The New Quarterly)

SARAH MEEHAN SIRK

Moonman

(from Taddle Creek)

EMILY BOSSÉ

Last Animal Standing on Gentleman’s Farm

(from The Fiddlehead)

RON SCHAFRICK

Lovely Company

(from Plenitude Magazine)

CHARLIE FISET

Maggie’s Farm

(from The Fiddlehead)<

br />

MADELEINE MAILLET

Achilles’ Death

(from Matrix)

ANNA LING KAYE

Red Egg and Ginger

(from Prairie Fire)

DEIRDRE DORE

The Wise Baby

(from Geist)

About the Contributors

About the Contributing Publications

Previous Contributing Authors

INTRODUCTION

When you’re handed ninety-six short stories—a record number of submissions for the Journey Prize—and given a limited amount of time to read, ponder, and form opinions about them, it’s hard not to feel overwhelmed and underqualified.

So as jury members we each came up with a plan of attack. We made schedules and swore to read two short stories every morning in order to meet the deadline. We sat down with twenty, thirty, forty pages and several cups of coffee and tried to put everything out of our heads: what our fellow jury members would think of a certain story, what they’d think of any one of us for saying we liked it; what should a Canadian short story look like; what are the criteria for good, for better, for best.

We read and we read and we read.

We slipped into the stories themselves and started to think about what themes, what places, what ideas are preoccupying Canadian writers. Sure, there are lakes and cabins, but there’s also the apocalypse and politics with both capital and small P’s. There are strange characters and seemingly ordinary ones. There are wrestlers and ghosts—sometimes together in the same story.

Eventually, even those thoughts went away; once we were sucked into a story, all those questions and concerns simply evaporated. It was when we found ourselves longing to talk about a character, or a moment, or a scene, or thinking about a story or a setting while washing the dishes, that it became clear: we’d found it. We found what makes good, better, best—and we hoped the other jury members did too.

But we knew our individual experiences of a story wouldn’t necessarily be corroborated by another’s experience of the same story. So we were sweating (just a bit) the face-to-face meeting with our fellow jurors, where we’d be obliged to defend our personal favourites. Coming together as a jury forced us to formulate criteria with which to evaluate our choices—forced us, too, to question our assumptions about what ingredients make for a good story. How important, for example, is polish and technical skill? Of course, structural integrity should never be discounted; and yet, and yet. What about the rough stone that knocks a hole in your chest? What about the piece that rambles but pleases the senses?

Does the size of the story matter? Does the depth and ambition of the story matter? Does originality trump a classically elegant construction?

Well.

There’s no telling where emotion comes from, but there were times when we read a story and we just knew: this is really fucking good.

What we were looking for underwent subtle changes during our conversation. If a story had a voice we couldn’t get enough of; if our curiosity was piqued; if we laughed; if an ending gave us chills—maybe the rawness didn’t matter quite so much. How to quantify the mystery, the magic of a smashingly good read?

In the end, we embraced the simple pleasure of discovery.

We wanted, as readers, to encounter stories that were not all the same. Some stories in this anthology challenge, and others charm; some play with language, and others cleave to form; some are raw, some more polished. This collection is proof that a story well-told comes in a variety of shapes, sizes, voices, and forms.

The one thing we wanted most, and that unified us in our discussion, was the element of surprise in discovery. Good fiction should surprise, should be something you cannot turn away from. The twelve stories we’ve selected for this anthology are full of surprises. These writers surprised us with language and structure, they experimented with voice and dazzled us with the unexpected.

Perhaps the greatest surprise can be found in how these stories affected us. Some of the stories grabbed us from the very beginning, while others rippled out like water disturbed by a pebble. Regardless of how they took hold, they all engaged us with their richness—the layered and nuanced telling of that story. The more we discussed their individual merits, the more we appreciated how beautiful or smart or gritty these pieces were.

The stories we’ve chosen are all well-crafted pieces that tantalized us, made us question what we think we know, and provoked us with unfamiliar worlds. The sheer diversity of styles and the breadth and depth of subject matter showed us that literary journals and magazines in this country play an extraordinary role in shaping Canadian literature.

This whole process has confirmed for us that the short story form is flourishing.

Expect pleasure. Expect delight. Expect surprise. Expect these twelve writers to emerge as some of this country’s most interesting voices.

Anthony De Sa

Tanis Rideout

Carrie Snyder

April 2015

LORI MCNULTY

FINGERNECKLACE

Peppermint saliva lips, two numb bums. Lick, stamp, stick around the salvaged oak table in the common room where Joe and Gus compete on Fish Friday. First one to lick and label five hundred envelopes gets his pick of the fresh cod Mrs. B will serve tonight with garlicky roasted red peppers.

“All good, my jumblies?” Mrs. B scans the mail metropolis forming at Gus’s elbows. “Break for fresh air?”

Joe stomps his feet. Gus pinches a perfect three-fold letter, head low. “Suit yourselves.”

Mrs. B has been group home supervisor since her husband accidentally shot himself eight years ago. Now she pitches lifebuoys in a sinking, four-storey heritage house in Greektown that Gus calls the HMS Shitstorm. Tomorrow, when she’s flat-lining on the couch with a migraine, he’ll try to kiss her on the lips.

Joe flicks the long braid that dangles down his back like a fat black squirrel tail. Whenever he squirms, Gus feels the rodent claw up his own spine.

“Don’t steal my Cheerios,” Gus howls, slapping Joe’s hand away from the cereal bowl between them. Gus pulls the mournful face that makes him look like a plumpish fifty-plus, though he’s only thirty-six.

“You chew like an Indian,” Gus shouts.

“You stink like catfish,” Joe replies, stomping his lizard-skin boots. His face is braided with sun and age, soft as kid leather.

Marlee enters, slumps down next to Gus, who is quietly nibbling at the edge of an O. She and Gus grew up on the wrong side of sane so they’re next-door neighbours. Nuthouse Knobs. Crackpot Criminals. The Deranged. Marlee came in off the streets, the thing men fucked behind dumpsters. Now, she’s on low-grade watch at the home. Not that she’d ever go through with it, but one rainy afternoon she swallowed a jar of paint thinner just to wash the stench from her throat. The last time Gus acted out—packed his life in a duffel and hitched the Don Valley to his brother’s place—Donny sent him back on the Greyhound from Peterborough, pronto. That was two summers ago. He’s been good all year.

Mrs. B returns, pointing to her watch. Gus plucks two skinny whites from his silver pillbox. He’ll be slow-mo soon, bleary by dinner.

The rice is one item on the plate. The rice is yellow and smells like buttered bones. The red peppers curl, sodden and sad in their oily, garlic swim. At the dinner table, Gus pokes at his rumpled fish, feeling his organs flip.

“Last time,” Mrs. B says, rising from the table. She fixes Gus a peanut butter sandwich she glues together with clover honey. With a quick flash of her blade, she splits the sandwich four ways. Dropping the plate before Gus, she taps the table.

Gus is squeezing his head. He can see his mother’s ash fingers tap-tap the ashtray. She is butting the stub out, covering her ears. Can’t stop the blue-splitting shrieks.

“Come on, Gus,” Mrs. B taps again. He shakes his head, tries sorting patterns on his mother’s peeling yellow linoleum.

“You need your energy. Donny’s coming tomorrow,” she adds.

/>

Donny’s greasy jeans are tucked into oil-stained work boots in the living room of the care home. He checks his watch, pacing. Crew’s on site. Fuck. Shit. Piss. He’s got the engineer’s change orders. Cost overruns. Goddamn job is killing him. Looking up he sees Gus lumbering down the stairs still wrapped in his white terry cloth robe. Big as a hollowed oak, premature belly spread. Donny shakes a full prescription bottle at him.

“Don’t skip out on me, Gus. You know what happens.”

Donny watches his younger brother’s eyes dart around the room, taking inventory. He sees Gus freeze at the sight of his work boots.

Gus bunches the terry cloth belt in his palms, squeezes, lets the fuzzy ball drop to the floor. He yanks it back up like a fishing line, absently lets it drop. Donny pats the couch cushion, coaxing his brother over.

“Look, Gus, we can’t do our usual pizza run this aft. Got a date with a wrecking ball.”

Gus bunches the belt in his lap, blinks wet, wandering tears. Donny wraps his arms around his big old stump of a baby brother, tries to hold the roots down, keep the disease from spreading. Root rot. Runs in the family.

Gus sobs into his brother’s neck. “I want to come home.”

Donny holds him close, tries to stop twenty years of trembling. Five years, six major episodes, a thousand pills and private dreams between them.

He can see it in his brother’s puffy eyelids, the grey, candle-drip skin. New meds are doing a number. He looks more like her now. Same mess of auburn hair, same staple-sized crease below his lip. Donny pictures his mother seated on the stairs, the dim glow of her after-dinner cigarette, eyes going in all directions. And Gus at nine years old, past the biting and moodiness, withdrawing into his mumble mouth, doing after-dinner dishes in the pyjamas he’s worn all day. While Donny fucks off to his buddy Cheevie’s house for double dessert. Cheevie has Nintendo on the set, a mother who never once tried to pry open their bedroom door with a chef’s knife. Smooth exit, just like the old man.

Donny loosens the belt around his brother’s waist. “Gus, you can’t come home. You know Pinky’s happy as horses with the house all quiet.”

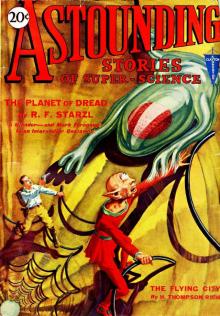

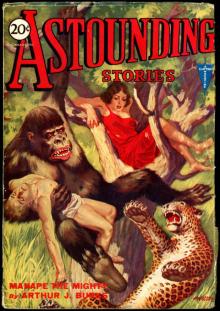

Astounding Stories, March, 1931

Astounding Stories, March, 1931 Astounding Stories, February, 1931

Astounding Stories, February, 1931 Futuria Fantasia, Spring 1940

Futuria Fantasia, Spring 1940 The King's Daughter and Other Stories for Girls

The King's Daughter and Other Stories for Girls Uncanny Tales

Uncanny Tales Masters of Noir: Volume Two

Masters of Noir: Volume Two Witty Pieces by Witty People

Witty Pieces by Witty People Sylvaneth

Sylvaneth Space Wolves

Space Wolves Hammerhal & Other Stories

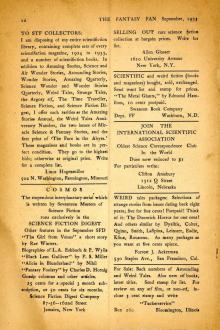

Hammerhal & Other Stories The Fantasy Fan, March, 1934

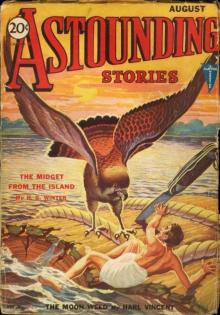

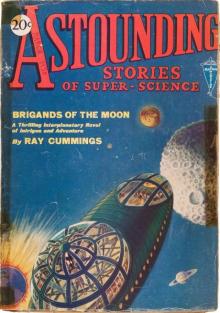

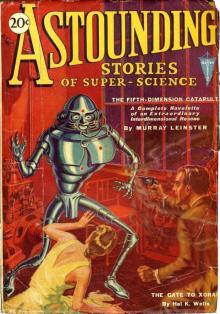

The Fantasy Fan, March, 1934 Astounding Stories of Super-Science, August 1930

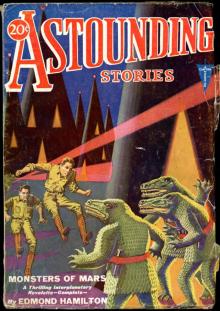

Astounding Stories of Super-Science, August 1930 Astounding Stories, August, 1931

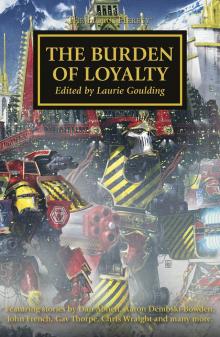

Astounding Stories, August, 1931 The Burden of Loyalty

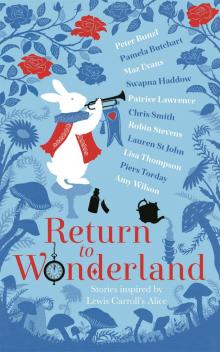

The Burden of Loyalty Return to Wonderland

Return to Wonderland Anthology - A Thousand Doors

Anthology - A Thousand Doors The Fantasy Fan, October 1933

The Fantasy Fan, October 1933 Astounding Stories, June, 1931

Astounding Stories, June, 1931 Southern Stories

Southern Stories Astounding Stories of Super-Science, May, 1930

Astounding Stories of Super-Science, May, 1930 The Fantasy Fan December 1933

The Fantasy Fan December 1933 Adventures in Many Lands

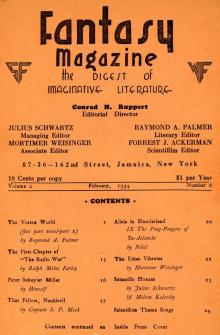

Adventures in Many Lands The Fantasy Fan February 1934

The Fantasy Fan February 1934 The Fantasy Fan November 1933

The Fantasy Fan November 1933 Astounding Stories, April, 1931

Astounding Stories, April, 1931 Fame and Fortune Weekly, No. 801, February 4, 1921

Fame and Fortune Weekly, No. 801, February 4, 1921 Astounding Stories of Super-Science, November, 1930

Astounding Stories of Super-Science, November, 1930 Astounding Stories of Super-Science January 1931

Astounding Stories of Super-Science January 1931 A Monk of Fife

A Monk of Fife Astounding Stories of Super-Science September 1930

Astounding Stories of Super-Science September 1930 Astounding Stories of Super-Science July 1930

Astounding Stories of Super-Science July 1930 Astounding Stories of Super-Science, June, 1930

Astounding Stories of Super-Science, June, 1930 Astounding Stories of Super-Science, October, 1930

Astounding Stories of Super-Science, October, 1930 Astounding Stories of Super-Science, March 1930

Astounding Stories of Super-Science, March 1930 The Fantasy Fan January 1934

The Fantasy Fan January 1934 The Fantasy Fan September 1933

The Fantasy Fan September 1933 Astounding Stories of Super-Science February 1930

Astounding Stories of Super-Science February 1930 Astounding Stories, May, 1931

Astounding Stories, May, 1931 Strange Stories of Colonial Days

Strange Stories of Colonial Days Golden Age of Science Fiction Vol IX

Golden Age of Science Fiction Vol IX Astounding Stories of Super-Science, December 1930

Astounding Stories of Super-Science, December 1930 Evolutions: Essential Tales of the Halo Universe

Evolutions: Essential Tales of the Halo Universe Good Stories Reprinted from the Ladies' Home Journal of Philadelphia

Good Stories Reprinted from the Ladies' Home Journal of Philadelphia Dragons!

Dragons! Murder Takes a Holiday

Murder Takes a Holiday Legacies of Betrayal

Legacies of Betrayal STAR WARS: TALES FROM THE CLONE WARS

STAR WARS: TALES FROM THE CLONE WARS Strange New Worlds 2016

Strange New Worlds 2016 Lippincott's Magazine, August, 1885

Lippincott's Magazine, August, 1885 Golden Age of Science Fiction Vol X

Golden Age of Science Fiction Vol X Hot Stuff

Hot Stuff Santa Wore Spurs

Santa Wore Spurs Paranormal Erotica

Paranormal Erotica Tangled Hearts: A Menage Collection

Tangled Hearts: A Menage Collection Sweet Tea and Jesus Shoes

Sweet Tea and Jesus Shoes The Journey Prize Stories 25

The Journey Prize Stories 25 Wild Western Tales 2: 101 Classic Western Stories Vol. 2 (Civitas Library Classics)

Wild Western Tales 2: 101 Classic Western Stories Vol. 2 (Civitas Library Classics) (5/15) The Golden Age of Science Fiction Volume V: An Anthology of 50 Short Stories

(5/15) The Golden Age of Science Fiction Volume V: An Anthology of 50 Short Stories (4/15) The Golden Age of Science Fiction Volume IV: An Anthology of 50 Short Stories

(4/15) The Golden Age of Science Fiction Volume IV: An Anthology of 50 Short Stories Ten Journeys

Ten Journeys The Boss

The Boss The Penguin Book of French Poetry

The Penguin Book of French Poetry Golden Age of Science Fiction Vol VIII

Golden Age of Science Fiction Vol VIII His Cinderella Housekeeper 3-in-1

His Cinderella Housekeeper 3-in-1 The Magazine of Fantasy & Science Fiction - July/August 2016

The Magazine of Fantasy & Science Fiction - July/August 2016 PYRATE CTHULHU - Tales of the Cthulhu Mythos (vol.2)

PYRATE CTHULHU - Tales of the Cthulhu Mythos (vol.2) Tales from a Master's Notebook

Tales from a Master's Notebook April 1930

April 1930 New Erotica 6

New Erotica 6 Damocles

Damocles The Longest Night Vol. 1

The Longest Night Vol. 1 The Golden Age of Science Fiction Volume VI: An Anthology of 50 Short Stories

The Golden Age of Science Fiction Volume VI: An Anthology of 50 Short Stories (1/15) The Golden Age of Science Fiction: An Anthology of 50 Short Stories

(1/15) The Golden Age of Science Fiction: An Anthology of 50 Short Stories Eye of Terra

Eye of Terra ONCE UPON A REGENCY CHRISTMAS

ONCE UPON A REGENCY CHRISTMAS Nexus Confessions

Nexus Confessions Passionate Kisses

Passionate Kisses War Without End

War Without End Doctor Who: Time Lord Fairy Tales

Doctor Who: Time Lord Fairy Tales Gotrek and Felix: The Anthology

Gotrek and Felix: The Anthology WESTERN CHRISTMAS PROPOSALS

WESTERN CHRISTMAS PROPOSALS The Journey Prize Stories 27

The Journey Prize Stories 27 The Silent War

The Silent War Liaisons

Liaisons Ellora's Cavemen: Tales from the Temple IV

Ellora's Cavemen: Tales from the Temple IV Ellora's Cavemen: Tales from the Temple II

Ellora's Cavemen: Tales from the Temple II Some of the Best From Tor.com, 2013 Edition: A Tor.Com Original

Some of the Best From Tor.com, 2013 Edition: A Tor.Com Original Urban Occult

Urban Occult Fractures

Fractures The Stories: Five Years of Original Fiction on Tor.com

The Stories: Five Years of Original Fiction on Tor.com The Penguin Book of Modern British Short Stories

The Penguin Book of Modern British Short Stories Mortarch of Night

Mortarch of Night The Portable Nineteenth-Century African American Women Writers

The Portable Nineteenth-Century African American Women Writers The Golden Age of Science Fiction Volume VII: An Anthology of 50 Short Stories

The Golden Age of Science Fiction Volume VII: An Anthology of 50 Short Stories Holy Bible: King James Version, The

Holy Bible: King James Version, The Eight Rooms

Eight Rooms sanguineangels

sanguineangels DarkNightsWithaBillionaireBundle

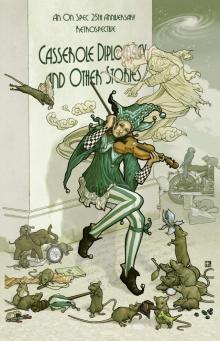

DarkNightsWithaBillionaireBundle Casserole Diplomacy and Other Stories

Casserole Diplomacy and Other Stories How I Survived My Summer Vacation

How I Survived My Summer Vacation Alfred Hitchcock Presents: 16 Skeletons From My Closet

Alfred Hitchcock Presents: 16 Skeletons From My Closet Lords, Ladies, Butlers and Maids

Lords, Ladies, Butlers and Maids The B4 Leg

The B4 Leg Ellora's Cavemen: Tales from the Temple I

Ellora's Cavemen: Tales from the Temple I 2014 Campbellian Anthology

2014 Campbellian Anthology There Is Only War

There Is Only War Obsidian Alliances

Obsidian Alliances 12 Gifts for Christmas

12 Gifts for Christmas Scary Holiday Tales to Make You Scream

Scary Holiday Tales to Make You Scream 25 For 25

25 For 25 The Plagues of Orath

The Plagues of Orath And Then He Kissed Me

And Then He Kissed Me Star Trek - Gateways 7 - WHAT LAY BEYOND

Star Trek - Gateways 7 - WHAT LAY BEYOND Laugh Your Head Off Again and Again

Laugh Your Head Off Again and Again The Balfour Legacy

The Balfour Legacy Golden Age of Science Fiction Vol XI

Golden Age of Science Fiction Vol XI (3/15) The Golden Age of Science Fiction Volume III: An Anthology of 50 Short Stories

(3/15) The Golden Age of Science Fiction Volume III: An Anthology of 50 Short Stories Shas'o

Shas'o Astounding Science Fiction Stories: An Anthology of 350 Scifi Stories Volume 2 (Halcyon Classics)

Astounding Science Fiction Stories: An Anthology of 350 Scifi Stories Volume 2 (Halcyon Classics) Twists in Time

Twists in Time Meduson

Meduson The Magazine of Fantasy & Science Fiction - August 1980

The Magazine of Fantasy & Science Fiction - August 1980 The Journey Prize Stories 22

The Journey Prize Stories 22 The Book that Made Me

The Book that Made Me Angels of Death Anthology

Angels of Death Anthology Ask the Bones

Ask the Bones Emergence

Emergence Beware the Little White Rabbit

Beware the Little White Rabbit Xcite Delights Book 1

Xcite Delights Book 1 Where flap the tatters of the King

Where flap the tatters of the King The Journey Prize Stories 21

The Journey Prize Stories 21 Tales of the Slayer, Volume II

Tales of the Slayer, Volume II Glass Empires

Glass Empires Golden Age of Science Fiction Vol XII

Golden Age of Science Fiction Vol XII (2/15) The Golden Age of Science Fiction Volume II: An Anthology of 50 Short Stories

(2/15) The Golden Age of Science Fiction Volume II: An Anthology of 50 Short Stories Fairytale Collection

Fairytale Collection Angels!

Angels! Golden Age of Science Fiction Vol XIII

Golden Age of Science Fiction Vol XIII