The Portable Nineteenth-Century African American Women Writers Read online

PENGUIN CLASSICS

THE PORTABLE NINETEENTH-CENTURY AFRICAN AMERICAN WOMEN WRITERS

HOLLIS ROBBINS, PH.D., is Director of the Center for Africana Studies at Johns Hopkins University and Chair of the Humanities Department at the Peabody Institute, where she has taught since 2006. Her work focuses on the intersection of nineteenth-century American and African American literature and the discourses of law, bureaucracy, and the press. Robbins has edited or coedited four books on nineteenth-century African American literature, including the Penguin edition of Frances E. W. Harper’s 1892 novel Iola Leroy, or Shadows Uplifted. She is also the coeditor with Henry Louis Gates, Jr., of The Annotated Uncle Tom’s Cabin (2006) and In Search of Hannah Crafts (2004). She is currently completing a monograph, Forms of Contention: The African American Sonnet Tradition.

HENRY LOUIS GATES, JR., is the Alphonse Fletcher University Professor and founding director of the Hutchins Center for African and African American Research at Harvard University. He is editor in chief of the Oxford African American Studies Center and TheRoot.com, and creator of the highly praised PBS documentary The African Americans: Many Rivers to Cross. He is general editor for a Penguin Classics series of African American works.

PENGUIN BOOKS

An imprint of Penguin Random House LLC

375 Hudson Street

New York, New York 10014

penguin.com

Introduction, notes and selection copyright © 2017 by Hollis Robbins and Henry Louis Gates, Jr.

General introduction copyright © 2008 by Henry Louis Gates, Jr.

Penguin supports copyright. Copyright fuels creativity, encourages diverse voices, promotes free speech, and creates a vibrant culture. Thank you for buying an authorized edition of this book and for complying with copyright laws by not reproducing, scanning, or distributing any part of it in any form without permission. You are supporting writers and allowing Penguin to continue to publish books for every reader.

Selections from The Bondwoman’s Narrative by Hannah Crafts, edited by Henry Louis Gates, Jr. Copyright © 2002, 2003 by Henry Louis Gates, Jr. Reprinted with permission of Grand Central Publishing.

Ebook ISBN: 9780143130673

LIBRARY OF CONGRESS CATALOGING-IN-PUBLICATION DATA

Names: Robbins, Hollis, 1963– editor. | Gates, Henry Louis, Jr., editor.

Title: The portable nineteenth-century African American women writers / edited with an introduction by Hollis Robbins and Henry Louis Gates, Jr. ; general editor, Henry Louis Gates, Jr.

Description: New York : Penguin Books, 2017. | Series: Penguin Classics

Identifiers: LCCN 2017004173 | ISBN 9780143105992 (paperback)

Subjects: LCSH: American literature—African American authors. | American literature—Women authors. | American literature—19th century. | African American women—Literary collections. | BISAC: FICTION / African American / General. | FICTION / Anthologies (multiple authors).

Classification: LCC PS508.N3 P596 2017 | DDC 810.8/0928708996073—dc23

LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2017004173

Cover photograph: Women’s League, Newport, R.I., Courtesy of the Library of Congress, LC-USZ62-51555.

Version_2

Contents

About the Editors

Title Page

Copyright

What Is an African American Classic? by HENRY LOUIS GATES, JR.

Introduction by HOLLIS ROBBINS and HENRY LOUIS GATES, JR.

Suggestions for Further Reading

THE PORTABLE NINETEENTH-CENTURY AFRICAN AMERICAN WOMEN WRITERS

PERSONAL ACCOUNTS OF ABOLITION AND FREEDOM

1. Anonymous (no date)

“Address to the Female Literary Association of Philadelphia, on Their First Anniversary: By a Member” (1832)

2. Sojourner Truth (ca. 1797–1883)

“Speech Delivered to Women’s Rights Convention in Akron Ohio” (1851)

Anti-Slavery Bugle Version (1851)

Frances D. Gage Version (1863)

Selections on Western Settlement from Narrative of Sojourner Truth (1875)

Petition to Congress.

“Truths from Sojourner Truth”

From The N.Y. Tribune. Sojourner Truth at Work.

3. Mary Prince (ca. 1788–after 1833)

Excerpt from The History of Mary Prince, a West Indian Slave (1831)

4. Nancy Prince (1799–after 1856)

From A Narrative of the Life and Travels of Mrs. Nancy Prince (1850)

5. Maria W. Stewart (ca. 1803–1879)

“An Address Delivered at the African Masonic Hall” (1833)

6. Sarah Mapps Douglass (Zillah) (1806–1882)

“A Mother’s Love” (1832)

7. Harriet Jacobs (1813–1897)

“The Loophole of Retreat” from Incidents in the Life of a Slave Girl (1861)

8. Elizabeth Keckley (1818–1907)

“The Secret History of Mrs. Lincoln’s Wardrobe in New York,” from Behind the Scenes, or, Thirty Years a Slave and Four Years in the White House (1868)

9. Eliza Potter (1820–after 1861)

“New Orleans,” from A Hairdresser’s Experience in High Life (1859)

10. Harriet Wilson (1825–1900)

Selections from Our Nig (1859)

Preface

Chapter I: Mag Smith, My Mother.

Chapter XII: The Winding Up of the Matter.

11. Hannah Crafts/Bond (1826–after 1859)

Selections from The Bondwoman’s Narrative (ca. 1858)

Chapter 1: In Childhood

Chapter 13: A Turn of the Wheel

12. Sarah Parker Remond (1826–1894)

“The Negroes in the United States of America” (1862)

13. Louisa Picquet (ca. 1829–1896)

“The Family Sold at Auction—Louisa Bought by a ‘New Orleans Gentleman,’ and What Came of it,” from The Octoroon (1861)

FUGITIVES AND EMIGRANTS: MOVING WEST AND NORTH

14. Mrs. John Little (no date)

“Mrs. John Little,” from The Refugee: Narratives of Fugitive Slaves in Canada (1856)

15. Mary Ann Shadd Cary (1823–1893)

Selections from A Plea for Emigration, or, Notes of Canada West (1852)

Settlements,—Dawn,—Elgin,—Institution,—Fugitive Home

Political Rights—Election Law—Oath—Currency.

16. Jennie Carter (Semper Fidelis) (ca. 1830–1881)

“Letter from Nevada County: Mud Hill, September 2, 1868” (1868)

“Letter from Nevada County: Mud Hill, September 12, 1868” (1868)

17. Abby Fisher (ca. 1832–after 1881)

Selections from What Mrs. Fisher Knows About Old Southern Cooking, Soups, Pickles, Preserves, Etc. (1881)

Preface and Apology

Jumberlie—A Creole Dish

Oyster Gumbo Soup

Tonic Bitters—A Southern Remedy for Invalids

Sweet Cucumber Pickles

Pap for Infant Diet

NORTHERN WOMEN AND THE POST-WAR SOUTH

18. Charlotte Forten Grimké (1837–1914)

“Life on the Sea Islands” (1864)

“Charles Sumner, On Seeing Some Pictures of the Interior of His House” (1874)

“The Gathering of the Grand Army” (1890)

19. Josephine St. Pierre Ruffin (1842–1924)

“Address to the First National Conference of Colored Women” (1895)

“An Open Letter to the Educational League of Georgia” (1889)

20. Edmonia Goodelle Highgate (1844–1870)

“A Spring Day Up the James” (1865)

“Rainy-Day Ink Drops” (1865)

“Neglected Opportunities” (1866)

“On Horse Back—Saddle Dash, No. 1” (1866)

MEMOIRS: LOOKING BACK

21. Julia A. J. Foote (1823–1900)

Selections from A Brand Plucked from the Fire (1879)

Chapter I: Birth and Parentage

Chapter IV: My Teacher Hung for Crime

Chapter XIX: Public Effort—Excommunication

Chapter XXII: A Visit to My Parents—Further Labors

22. Jarena Lee (1783–1855)

Selection from Religious Experience and Journal of Mrs. Jarena Lee, Giving an Account of Her Call to Preach the Gospel (1849)

My Call to Preach the Gospel.

23. Zilpha Elaw (1790–after 1845)

Selection from Memoirs of the Life, Religious Experience, Ministerial Travels and Labours of Mrs. Zilpha Elaw, an American Female of Colour (1846)

24. Lucy Delaney (ca. 1830–after 1891)

Selections from From Darkness Cometh the Light (1891)

Chapter IV.

Chapter V.

25. Ella Sheppard (1851–1914)

“Historical Sketch of the Jubilee Singers” (1911)

POETRY, DRAMA, AND FICTION

26. Sarah Forten Purvis (Magawisca) (1814–1884)

“The Slave Girl’s Address to Her Mother” (1831)

“The Abuse of Liberty” (1831)

“Lines” (1838)

27. Ann Plato (ca. 1820–after 1841)

“Education” (1841)

“The Natives of America” (1841)

28. Julia Collins (unknown–1865)

Selections from The Curse of Caste; or The Slave Bride (1865)

Chapter VI.

Chapter VIII: The Flower Fadeth.

Chapter X: Richard in New Orleans.

Chapter XXVII: Mrs. Butterworth’s Revelation.

Chapter XXIX: Convalescent.

29. Frances Ellen Watkins Harper (1825–1911)

“Enlightened Motherhood: An Address Before the Brooklyn Literary Society, November 15, 1892”

Newfound Poems from Forest Leaves (ca. 1840)

“Haman and Mordecai”

“A Dream”

“The Felon’s Dream”

Later Poems

“Eliza Harris”

“The Slave Auction”

“Lines”

“Bible Defence of Slavery”

“The Drunkard’s Child”

“The Revel”

“Ethiopia”

“To Mrs. Harriet Beecher Stowe”

“The Fugitive’s Wife”

“An Appeal to My Countrywomen”

30. Pauline Hopkins (1859–1930)

Selections from Peculiar Sam, or, the Underground Railroad, a Musical Drama in Four Acts (1879)

Act III

Act IV

“Talma Gordon” (1900)

31. Katherine Davis Chapman Tillman (Kate D. Chapman) (1870–after 1922)

“A Question of To-day” (1889)

“Lines to Ida B. Wells” (1894)

“A Tribute to Negro Regiments” (1898)

32. Amelia E. Johnson (ca. 1858–1922)

Selections from Clarence and Corinne, or God’s Way (1890)

Chapter I: Discouraged.

Chapter IV: Provided For.

33. Mary E. Ashe Lee (1850–1932)

“Afmerica” (1885)

34. H. Cordelia Ray (1849–1916)

“Lincoln” (1876)

“To My Father” (1893)

“Shakespeare” (1893)

“In Memoriam (Frederick Douglass)” (1897)

“William Lloyd Garrison” (1905)

35. Sarah E. Farro (1859–after 1937)

Chapter 1 from True Love: A Story of English Domestic Life (1891)

36. Alice Ruth Moore Dunbar-Nelson (1875–1935)

“The Woman” (1895)

“Amid the Roses” (1895)

“I Sit and Sew” (1918)

“Sonnet” (1919)

“To the Negro Farmers of the United States” (1920)

“To Madame Curie” (1921)

WOMEN ADDRESSING WOMEN: ADDRESSES AND ESSAYS

37. Sarah J. Early (1825–1907)

“The Organized Efforts of the Colored Women of the South to Improve Their Condition” (1894)

38. Lucy Craft Laney (1854–1933)

“The Burden of the Educated Colored Woman” (1899)

39. Fannie Barrier Williams (1855–1944)

“The Intellectual Progress of the Colored Woman of the United States since the Emancipation Proclamation” (1893)

40. Virginia W. Broughton (1856–1934)

“Woman’s Work” (1894)

41. Anna Julia Cooper (1860–1964)

“Womanhood a Vital Element in the Regeneration and Progress of a Race” (1886)

“Paper by Mrs. Anna J. Cooper” (1894)

42. Mary Church Terrell (1863–1954)

“The Progress of Colored Women” (1898)

“The Convict Lease System and the Chain Gangs” (1907)

43. Mary V. Cook (1863–1945)

“Women’s Place in the Work of the Denomination” (1887)

EDUCATION AND SOCIAL REFORM

44. Julia Caldwell-Frazier (1863–1929)

“The Decisions of Time” (1889)

45. Fanny M. Jackson Coppin (1837–1913)

“Commencement Address” (1876)

A Race’s Progress.

“Christmas Eve Story” (1880)

“A Plea for the Mission School” (1891)

“A Plea for Industrial Opportunity” (1879)

46. Victoria Earle Matthews (1861–1907)

“The Value of Race Literature” (1895)

47. Gertrude Bustill Mossell (1855–1948)

“Baby Bertha’s Temperance Lesson” (1885)

“Will the Negro Share the Glory That Awaits Africa?” (1893)

48. Amelia L. Tilghman (1856–1931)

“Dedicated to Her Gracious Majesty, Queen Victoria, of England” (1892)

49. Josephine J. Turpin Washington (1861–1949)

“A Great Danger” (1884)

Annie Porter Excoriated.

“The Province of Poetry” (1889)

“Needs of Our Newspapers: Some Reasons for Their Existence” (1889)

“Anglo Saxon Supremacy” (1890)

50. Ida B. Wells-Barnett (1862–1931)

“Our Women” (1887)

“The Requirements of Southern Journalism” (1893)

“Lynch Law and the Color Line” (1893)

“Our Country’s Lynching Record” (1913)

“The Ordeal of the ‘Solitary’: Mrs. Barnett Protests Against It” (1915)

WOMEN MEMORIALIZING WOMEN

51. S. Elizabeth Frazier (1864–1924)

“Some Afro-American Women of Mark” (1892)

52. Lucy Wilmot Smith (1861–1890)

“Women as Journalists: Portraits and Sketches of a Few of the Women Journalists of the Race” (1889)

Acknowledgments

What Is an African American Classic?

I have long nurtured a deep and abiding affection for the Penguin Classics, at least since I was an undergraduate at Yale. I used to imagine that my attraction for these books—grouped together, as a set, in some indepen

dent bookstores when I was a student, and perhaps even in some today—stemmed from the fact that my first-grade classmates, for some reason that I can’t recall, were required to dress as penguins in our annual all-school pageant, and perform a collective side-to-side motion that our misguided teacher thought she could choreograph into something meant to pass for a “dance.” Piedmont, West Virginia, in 1956, was a very long way from Penguin Nation, wherever that was supposed to be! But penguins we were determined to be, and we did our level best to avoid wounding each other with our orange-colored cardboard beaks while stomping out of rhythm in our matching orange, veined webbed feet. The whole scene was madness, one never to be repeated at the Davis Free School. But I never stopped loving penguins. And I have never stopped loving the very audacity of the idea of the Penguin Classics, an affordable, accessible library of the most important and compelling texts in the history of civilization, their black-and-white spines and covers and uniform type giving each text a comfortable, familiar feel, as if we have encountered it, or its cousins, before. I think of the Penguin Classics as the very best and most compelling in human thought, an Alexandrian library in paperback, enclosed in black and white.

I still gravitate to the Penguin Classics when killing time in an airport bookstore, deferring the slow torture of the security lines. Sometimes I even purchase two or three, fantasizing that I can speed-read one of the shorter titles, then make a dent in the longer one, vainly attempting to fill the holes in the liberal arts education that our degrees suggest we have, over the course of a plane ride! Mark Twain once quipped that a classic is “something that everybody wants to have read and nobody wants to read,” and perhaps that applies to my airport purchasing habits. For my generation, these titles in the Penguin Classics form the canon—the canon of the texts that a truly well-educated person should have read, and read carefully and closely, at least once. For years I rued the absence of texts by black authors in this series, and longed to be able to make even a small contribution to the diversification of this astonishingly universal list. I watched with great pleasure as titles by African American and African authors began to appear, some two dozen over the past several years. So when Elda Rotor approached me about editing a series of African American classics and collections for Penguin’s Portable Series, I eagerly accepted.

Thinking about the titles appropriate for inclusion in these series led me, inevitably, to think about what, for me, constitutes a “classic.” And thinking about this led me, in turn, to the wealth of reflections on what defines a work of literature or philosophy somehow speaking to the human condition beyond time and place, a work somehow endlessly compelling, generation upon generation, a work whose author we don’t have to look like to identify with, to feel at one with, as we find ourselves transported through the magic of a textual time machine; a work that refracts the image of ourselves that we project onto it, regardless of our ethnicity, our gender, our time, our place. This is what centuries of scholars and writers have meant when they use the word classic, and—despite all that we know about the complex intersubjectivity of the production of meaning in the wondrous exchange between a reader and a text—it remains true that classic texts, even in the most conventional, conservative sense of the word classic, do exist, and these books will continue to be read long after the generation the text reflects and defines, the generation of readers contemporary with the text’s author, is dead and gone. Classic texts speak from their authors’ graves, in their names, in their voices. As Italo Calvino once remarked, “A classic is a book that has never finished saying what it has to say.”

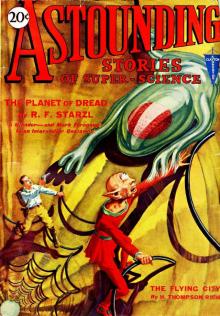

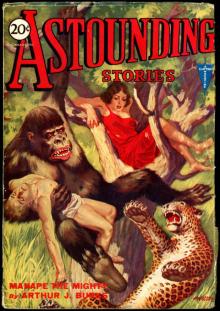

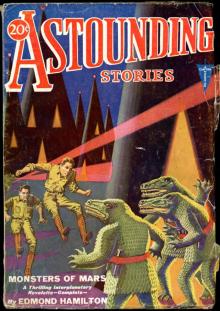

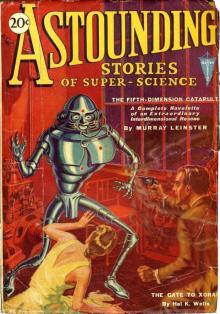

Astounding Stories, March, 1931

Astounding Stories, March, 1931 Astounding Stories, February, 1931

Astounding Stories, February, 1931 Futuria Fantasia, Spring 1940

Futuria Fantasia, Spring 1940 The King's Daughter and Other Stories for Girls

The King's Daughter and Other Stories for Girls Uncanny Tales

Uncanny Tales Masters of Noir: Volume Two

Masters of Noir: Volume Two Witty Pieces by Witty People

Witty Pieces by Witty People Sylvaneth

Sylvaneth Space Wolves

Space Wolves Hammerhal & Other Stories

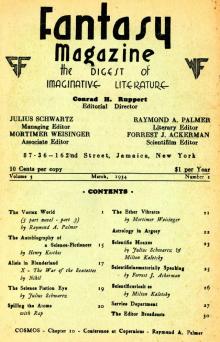

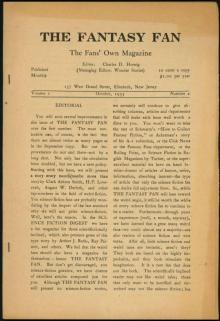

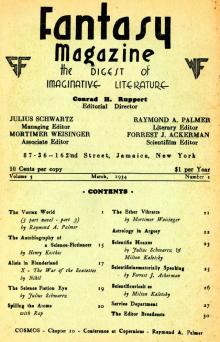

Hammerhal & Other Stories The Fantasy Fan, March, 1934

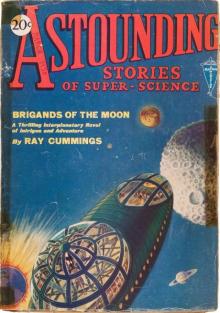

The Fantasy Fan, March, 1934 Astounding Stories of Super-Science, August 1930

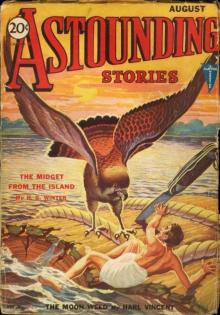

Astounding Stories of Super-Science, August 1930 Astounding Stories, August, 1931

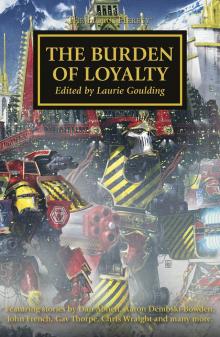

Astounding Stories, August, 1931 The Burden of Loyalty

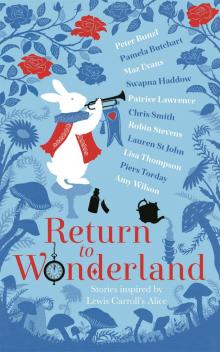

The Burden of Loyalty Return to Wonderland

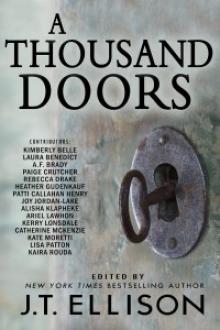

Return to Wonderland Anthology - A Thousand Doors

Anthology - A Thousand Doors The Fantasy Fan, October 1933

The Fantasy Fan, October 1933 Astounding Stories, June, 1931

Astounding Stories, June, 1931 Southern Stories

Southern Stories Astounding Stories of Super-Science, May, 1930

Astounding Stories of Super-Science, May, 1930 The Fantasy Fan December 1933

The Fantasy Fan December 1933 Adventures in Many Lands

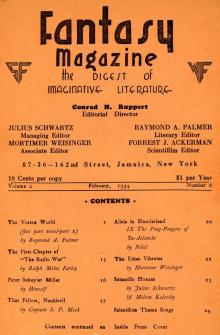

Adventures in Many Lands The Fantasy Fan February 1934

The Fantasy Fan February 1934 The Fantasy Fan November 1933

The Fantasy Fan November 1933 Astounding Stories, April, 1931

Astounding Stories, April, 1931 Fame and Fortune Weekly, No. 801, February 4, 1921

Fame and Fortune Weekly, No. 801, February 4, 1921 Astounding Stories of Super-Science, November, 1930

Astounding Stories of Super-Science, November, 1930 Astounding Stories of Super-Science January 1931

Astounding Stories of Super-Science January 1931 A Monk of Fife

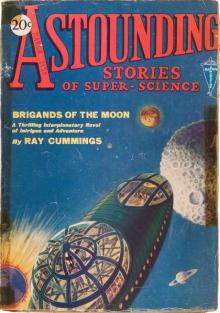

A Monk of Fife Astounding Stories of Super-Science September 1930

Astounding Stories of Super-Science September 1930 Astounding Stories of Super-Science July 1930

Astounding Stories of Super-Science July 1930 Astounding Stories of Super-Science, June, 1930

Astounding Stories of Super-Science, June, 1930 Astounding Stories of Super-Science, October, 1930

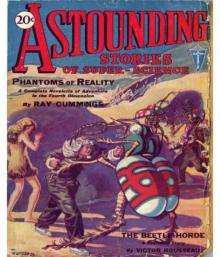

Astounding Stories of Super-Science, October, 1930 Astounding Stories of Super-Science, March 1930

Astounding Stories of Super-Science, March 1930 The Fantasy Fan January 1934

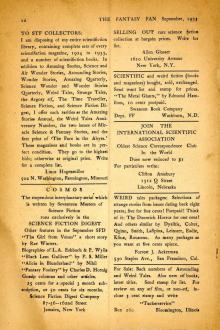

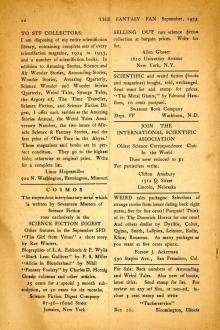

The Fantasy Fan January 1934 The Fantasy Fan September 1933

The Fantasy Fan September 1933 Astounding Stories of Super-Science February 1930

Astounding Stories of Super-Science February 1930 Astounding Stories, May, 1931

Astounding Stories, May, 1931 Strange Stories of Colonial Days

Strange Stories of Colonial Days Golden Age of Science Fiction Vol IX

Golden Age of Science Fiction Vol IX Astounding Stories of Super-Science, December 1930

Astounding Stories of Super-Science, December 1930 Evolutions: Essential Tales of the Halo Universe

Evolutions: Essential Tales of the Halo Universe Good Stories Reprinted from the Ladies' Home Journal of Philadelphia

Good Stories Reprinted from the Ladies' Home Journal of Philadelphia Dragons!

Dragons! Murder Takes a Holiday

Murder Takes a Holiday Legacies of Betrayal

Legacies of Betrayal STAR WARS: TALES FROM THE CLONE WARS

STAR WARS: TALES FROM THE CLONE WARS Strange New Worlds 2016

Strange New Worlds 2016 Lippincott's Magazine, August, 1885

Lippincott's Magazine, August, 1885 Golden Age of Science Fiction Vol X

Golden Age of Science Fiction Vol X Hot Stuff

Hot Stuff Santa Wore Spurs

Santa Wore Spurs Paranormal Erotica

Paranormal Erotica Tangled Hearts: A Menage Collection

Tangled Hearts: A Menage Collection Sweet Tea and Jesus Shoes

Sweet Tea and Jesus Shoes The Journey Prize Stories 25

The Journey Prize Stories 25 Wild Western Tales 2: 101 Classic Western Stories Vol. 2 (Civitas Library Classics)

Wild Western Tales 2: 101 Classic Western Stories Vol. 2 (Civitas Library Classics) (5/15) The Golden Age of Science Fiction Volume V: An Anthology of 50 Short Stories

(5/15) The Golden Age of Science Fiction Volume V: An Anthology of 50 Short Stories (4/15) The Golden Age of Science Fiction Volume IV: An Anthology of 50 Short Stories

(4/15) The Golden Age of Science Fiction Volume IV: An Anthology of 50 Short Stories Ten Journeys

Ten Journeys The Boss

The Boss The Penguin Book of French Poetry

The Penguin Book of French Poetry Golden Age of Science Fiction Vol VIII

Golden Age of Science Fiction Vol VIII His Cinderella Housekeeper 3-in-1

His Cinderella Housekeeper 3-in-1 The Magazine of Fantasy & Science Fiction - July/August 2016

The Magazine of Fantasy & Science Fiction - July/August 2016 PYRATE CTHULHU - Tales of the Cthulhu Mythos (vol.2)

PYRATE CTHULHU - Tales of the Cthulhu Mythos (vol.2) Tales from a Master's Notebook

Tales from a Master's Notebook April 1930

April 1930 New Erotica 6

New Erotica 6 Damocles

Damocles The Longest Night Vol. 1

The Longest Night Vol. 1 The Golden Age of Science Fiction Volume VI: An Anthology of 50 Short Stories

The Golden Age of Science Fiction Volume VI: An Anthology of 50 Short Stories (1/15) The Golden Age of Science Fiction: An Anthology of 50 Short Stories

(1/15) The Golden Age of Science Fiction: An Anthology of 50 Short Stories Eye of Terra

Eye of Terra ONCE UPON A REGENCY CHRISTMAS

ONCE UPON A REGENCY CHRISTMAS Nexus Confessions

Nexus Confessions Passionate Kisses

Passionate Kisses War Without End

War Without End Doctor Who: Time Lord Fairy Tales

Doctor Who: Time Lord Fairy Tales Gotrek and Felix: The Anthology

Gotrek and Felix: The Anthology WESTERN CHRISTMAS PROPOSALS

WESTERN CHRISTMAS PROPOSALS The Journey Prize Stories 27

The Journey Prize Stories 27 The Silent War

The Silent War Liaisons

Liaisons Ellora's Cavemen: Tales from the Temple IV

Ellora's Cavemen: Tales from the Temple IV Ellora's Cavemen: Tales from the Temple II

Ellora's Cavemen: Tales from the Temple II Some of the Best From Tor.com, 2013 Edition: A Tor.Com Original

Some of the Best From Tor.com, 2013 Edition: A Tor.Com Original Urban Occult

Urban Occult Fractures

Fractures The Stories: Five Years of Original Fiction on Tor.com

The Stories: Five Years of Original Fiction on Tor.com The Penguin Book of Modern British Short Stories

The Penguin Book of Modern British Short Stories Mortarch of Night

Mortarch of Night The Portable Nineteenth-Century African American Women Writers

The Portable Nineteenth-Century African American Women Writers The Golden Age of Science Fiction Volume VII: An Anthology of 50 Short Stories

The Golden Age of Science Fiction Volume VII: An Anthology of 50 Short Stories Holy Bible: King James Version, The

Holy Bible: King James Version, The Eight Rooms

Eight Rooms sanguineangels

sanguineangels DarkNightsWithaBillionaireBundle

DarkNightsWithaBillionaireBundle Casserole Diplomacy and Other Stories

Casserole Diplomacy and Other Stories How I Survived My Summer Vacation

How I Survived My Summer Vacation Alfred Hitchcock Presents: 16 Skeletons From My Closet

Alfred Hitchcock Presents: 16 Skeletons From My Closet Lords, Ladies, Butlers and Maids

Lords, Ladies, Butlers and Maids The B4 Leg

The B4 Leg Ellora's Cavemen: Tales from the Temple I

Ellora's Cavemen: Tales from the Temple I 2014 Campbellian Anthology

2014 Campbellian Anthology There Is Only War

There Is Only War Obsidian Alliances

Obsidian Alliances 12 Gifts for Christmas

12 Gifts for Christmas Scary Holiday Tales to Make You Scream

Scary Holiday Tales to Make You Scream 25 For 25

25 For 25 The Plagues of Orath

The Plagues of Orath And Then He Kissed Me

And Then He Kissed Me Star Trek - Gateways 7 - WHAT LAY BEYOND

Star Trek - Gateways 7 - WHAT LAY BEYOND Laugh Your Head Off Again and Again

Laugh Your Head Off Again and Again The Balfour Legacy

The Balfour Legacy Golden Age of Science Fiction Vol XI

Golden Age of Science Fiction Vol XI (3/15) The Golden Age of Science Fiction Volume III: An Anthology of 50 Short Stories

(3/15) The Golden Age of Science Fiction Volume III: An Anthology of 50 Short Stories Shas'o

Shas'o Astounding Science Fiction Stories: An Anthology of 350 Scifi Stories Volume 2 (Halcyon Classics)

Astounding Science Fiction Stories: An Anthology of 350 Scifi Stories Volume 2 (Halcyon Classics) Twists in Time

Twists in Time Meduson

Meduson The Magazine of Fantasy & Science Fiction - August 1980

The Magazine of Fantasy & Science Fiction - August 1980 The Journey Prize Stories 22

The Journey Prize Stories 22 The Book that Made Me

The Book that Made Me Angels of Death Anthology

Angels of Death Anthology Ask the Bones

Ask the Bones Emergence

Emergence Beware the Little White Rabbit

Beware the Little White Rabbit Xcite Delights Book 1

Xcite Delights Book 1 Where flap the tatters of the King

Where flap the tatters of the King The Journey Prize Stories 21

The Journey Prize Stories 21 Tales of the Slayer, Volume II

Tales of the Slayer, Volume II Glass Empires

Glass Empires Golden Age of Science Fiction Vol XII

Golden Age of Science Fiction Vol XII (2/15) The Golden Age of Science Fiction Volume II: An Anthology of 50 Short Stories

(2/15) The Golden Age of Science Fiction Volume II: An Anthology of 50 Short Stories Fairytale Collection

Fairytale Collection Angels!

Angels! Golden Age of Science Fiction Vol XIII

Golden Age of Science Fiction Vol XIII