The Journey Prize Stories 27 Read online

Page 12

In the fridge I found a casserole dish of rigatoni in tomato sauce—“noodles,” my father called it—that one of the PSWs had likely made the day before. I heated it up in the microwave and we ate that along with the chicken and coleslaw I’d brought. “Y’know,” my father said when we sat at the kitchen table, “she says she’s looking forward to meeting me.” Like the other day, he sounded proud, the way he reported this bit of information, as though no one had ever said that to him before, and when I think about it and the solitary life my father had always led, I wouldn’t be surprised if that were true. And then he said this odd thing: “The way she talks, she sounds like she’s always crying.” I could tell he found this trait both attractive and reminiscent of my mother. A lachrymose woman, my mother wept not only at sad movies but also, somewhat disturbingly, whenever she saw scenes on the news of natural disasters, war, or violent crime.

“You see,” my father said, waving a forkful of rigatoni, “you got a partner, so why shouldn’t I have a partner?”

I didn’t entirely follow my father’s logic (what if I had a disease?); I also didn’t tell him about the breakup. Although he’d met Michael many times over the years, my father and I weren’t close and I hardly ever told him anything related to my personal life. I also offer this as an example of the recent changes in my father’s diction. I’d never heard him use the word partner before; usually, he only ever said friend (as in, “Your friend there, does he have to come to the funeral?”), as if the word were something unpalatable he was forced to chew.

Shortly after three I heard the crunch of tires on gravel. We were both watching TV, my father and I, and when I went to the window I caught a brief glimpse of a young woman behind the wheel of a silver SUV and the shadowy figure of an old woman beside her.

“Company’s here,” my father said, clicking off the TV, and together we stepped out onto the porch. “Hello, hello,” he called out, waving happily, as he went round to the passenger side of the vehicle.

“Hi, I’m Lisa,” said the young woman when she slid out of the driver’s seat. “I’m in on Tuesdays and Thursdays for your dad.”

Since my mother died, I’d met several of these personal support workers. I’d met Courtney and Brittany (ridiculous pop-star names) and Stephanie, but it was the first time I was meeting Lisa.

“Isn’t it exciting?” she said, leaning in conspiratorially. “I told Barbara all about your dad. Y’know, I just thought they’re both around the same age, they’ve both lost a spouse, they’re both lonely. So I figure, why not?”

“Yes,” I said, smiling politely, observing up close that this woman was probably half my age, a kid of maybe twenty-two or twenty-three, a recent grad in social work no doubt. “Yes, why not.”

“So I said to Barbara, ‘There’s someone you just got to meet,’ and she told me she was so excited after they talked on the phone. ‘He sounds like a real sweetheart,’ she kept saying on the car ride over. Look at her, here she comes, all dolled up.”

And there she was, being led by the elbow by my smiling father, not at all the thin, wiry widow I’d expected, but a plump, regal-looking woman, like a dowager of some distinction. She was dressed in a white skirt and a matching white jacket over top of a white blouse flecked with tiny blue polka dots. A string of pearls hung from her neck and a pillar of tightly curled white hair crowned her head. “Hello, luv,” she said, extending her hand. “I’m Barbara.” And I heard what it was that made my father think she sounded like she was crying: it was the warble in her voice. She was English.

“Well, I’m off. Barbara—” Lisa called. “I’ll be back at five, okay?” She turned to me and whispered, “Let’s hope it works out,” and made a fingers-crossed gesture as she climbed back into her tank-like Ford Explorer.

“What a lovely home you have,” Barbara said when we entered the living room.

“My wife and I built it,” my father said, aiming her in the direction of the couch as he took his usual place in the armchair. “Have a seat.”

“So …” I said, clapping my hands together. “Coffee?”

“Tea, dear,” she said. “I’d love a cup of tea—with milk and sugar.”

“The usual for me,” my father said, referring to the thick, syrupy black coffee he consumed throughout the day.

As I poured water into the kettle and got the coffee maker going, I felt compelled to make as much noise as is possible when preparing coffee and boiling water so that I didn’t have to listen to their small talk. Perhaps it was because it embarrassed me that my father was on a date, and because I found the whole thing sad and symptomatic of the many changes he was undergoing. For the first time I wondered what my mother would make of all this, but just as quickly I saw her dismissively wave away the whole thing and tell my father, “Ach! Do what you want.” Although whether she meant that, I couldn’t be sure. I also realized I was in the uncomfortable and unnatural position of being my father’s chaperone, and I did not look forward to the conversation that would follow once Barbara left, the talk my father and I would have about her suitability as his bride and what she could bring to the marriage table, and the fierce quarrel that would inevitably ensue.

They were both laughing at something when I came back into the living room, and for a moment I caught the glimmer of something in their eyes, like a look of recognition—or relief: something that said, So glad to meet you. At last. “Did you put in sugar, luv?” Barbara said as I set a tray bearing two cups of coffee and one of tea onto the coffee table. She smiled at my father. “I have a weakness for sugar, you should know. And cream. And wine. Yet I’m as healthy as a horse, I’m told.”

“Me, I love my coffee,” my father said, raising his own cup as if making a toast.

In a way she did look like a bird, I thought, as I settled into the armchair opposite my father. A large, flightless bird, like a turkey, the way her neck was stooped and the thready skin beneath her chin flapped. She also had a long, beaky nose and small dark eyes, and I wondered if she’d been pretty when she was younger.

“So you’re from England,” I said, after a moment’s silence. She was sipping her tea and without turning her head she swivelled those avian eyes in my direction and smirked, as if what I’d said was the kind of banal observation she’d heard countless times and might have hoped I was above making. “How long you been in Canada?” I said, flustered, not knowing what else to say.

“Very good tea, dear, thank you.” She set her cup on its saucer. “More than forty years, to answer your question.”

“Really,” I said reflexively, and glanced up at the little clock on the wood-panelled hi-fi. The play would be well under way by now, I thought, and I wondered whom Michael had gone with, not that I knew any of the contingent of men in his life now; they were all just a slew of names to me, interchangeable.

“And before that we were in South Africa, Robert and I.” Barbara turned to my father. “You remember Robert?” she said. “I told you about him. On the phone?”

“Your husband you’re talking about,” my father said, midway between a statement and a question.

“We were there for several years,” Barbara said, fixing her gaze back onto me. “He was a banker, you see. But you can imagine it. The political situation … the strife …” She shook her head disdainfully. “So when a similar position opened up in Toronto, naturally he seized it.” She picked up her tea again, but instead of drinking from it, she cupped it in her palm and gazed at the picture window as if she were staring at a photo from long ago. “Nineteen sixty-eight it was when we came here.”

“That was the year me and my wife built this house,” my father said. “Nineteen sixty-eight.”

“And it certainly is a lovely home,” she said again, gazing disapprovingly about the room as though mentally disposing of the old curtains and wallpaper and putting up everything new. “But I had no idea how far out in the country you are. I said to Lisa, ‘Where are you taking me?’ That’s certainly going to ma

ke it difficult for this to work out since neither of us drives anymore.”

For this to work out. The words echoed in my head and, like a stalled truck, sat there.

“But why did you give up your licence, Bert?”

“I get disorientated,” my father said. “One time I was coming home from”—he gestured vaguely to the corner of the room—“what’s it called now? The mall over here? And I ended up way the heck over by Highway 20. I said to myself, ‘What the hell am I doing here?’ And that’s not the first time it happened either. I was supposed to go in to write the test, but I just figured, ach, forget it.”

“So you’re at home all the time now,” Barbara said.

I saw then what Lisa must have meant by “dolled up”: the subtle application of a faint but sparkly blue eyeshadow, nails that were painted a dazzling red; even her toenails were painted. The complete opposite of my mother, I thought. She was never one for cosmetics of any sort, my mother; occasionally she’d apply a clear polish to her nails, but that was the extent of it. Farm work was ill-suited for such extravagances. Barbara’s well-pedicured toes reminded me of my mother as she lay dying in the hospital, comatose from all the morphine they kept pumping into her: when the nurse pulled away the blanket to point out the mottling that had started in my mother’s bloated feet and legs—the sign that death wouldn’t be long in coming—I saw her long and filthy toenails, chipped and uncared for, and a strange and inexplicable combination of shame and sadness welled up within me.

“I’m stuck here,” my father said, throwing his hands up in the air.

Barbara shook her head. “You must get so lonely,” she said, as though she’d stumbled upon the thing that linked them together and that, hand in hand, they could conquer.

“Oh, I got the girls coming by every day,” my father said, downplaying any suggestion of loneliness. “They bring me my groceries and do the cooking and the cleaning. And I keep busy. There’s always grass to cut, and I do a little gardening in the greenhouse.”

“Oh, I know all about loneliness,” Barbara insisted. “I suppose this young man doesn’t know anything about that”—she smiled wistfully in my direction—“but thank goodness for my Lisa is all I’ve got to say. I just wouldn’t be able to manage without her. She’s a wonderful darling. Bathes me in the morning, makes me something to eat. Makes me my tea.” She sighed a little, as if the occasion called for it. “I’d die if it weren’t for her.”

—

Somehow we got onto the subject of church. Barbara said she belonged to an Anglican one in town, that it was walking distance from her house, and she wondered if we belonged to a church as well (we did, a Lutheran one, but we never went). She talked about her daughter, a woman who lived in Calgary with her second husband but seldom called home. “You’re lucky to have this young man living nearby,” Barbara said, once again smiling in my direction. “Angie wouldn’t care if I were dead or alive.” And then she sipped her tea, no longer delicately like before, but greedily, hungrily.

“The cake!” I said suddenly. “I forgot the coffee cake. Would you like some? Cinnamon apple, I think it is.”

“Just a small slice for me, luv,” Barbara said.

I was glad to get out of the room for a few minutes. My smile and false cheeriness had become an enormous strain and, like a diver at last reaching the water’s surface, I felt I could finally let go and breathe.

“Tell me, Bert,” I heard her say as I clattered about in the kitchen, looking for clean plates and forks, “have you ever been on a cruise?” I suspected my absence from the room offered an illusion of privacy necessary to pose this question. “I’m looking for someone to go on a cruise with,” she said.

“A cruise!” my father said. “I haven’t been on a boat since I came to Canada in ’57.”

“Here we are,” I said, smiling again as I returned to the living room. “Three coffee cakes.”

“Thank you, dear, looks lovely,” Barbara said. She turned to my father. “Oh, I love cruising. Robert and I used to go all the time. He took me to Barbados and Panama, the Italian coast and—where else did we go?—oh yes, and Alaska.”

“For how long?” my father asked.

“A week,” she said, lifting a forkful of cake to her mouth. She smiled wolfishly. “But two is better.”

“Hey, this cake is good,” my father said. “How much you pay for this?”

“Yes, very moist,” Barbara said. “Excellent choice.”

“It was on sale,” I said. “Zehrs.”

When a quiet moment had passed, Barbara said, “So, what do you think of my proposition?” She added enticingly, “The sun … the sea … lovely company …”

I could see my father turning it over in his head, trying to picture it the way one might catch the first glimpse of sun as it rises above the ocean.

“Y’know,” my father said, reaching for his coffee cup on the end table. He looked at me and smiled. “I always said one day I’d like to travel the world.”

I’d never heard my father say such a thing before, and I wondered if he meant it. Could he see himself in a bathing suit and sunglasses, lying on a deck chair next to this woman in similar attire? Could he see himself having cocktails in the evening, dressed in a dinner jacket and tie, mingling with other passengers? Could he see himself and Barbara dancing hand in hand on the dance floor? What would they have to talk about? What would he have in common with these people, the kind of people who take cruises?

“What more could you want, Bert?” Barbara said. “Nothing to worry about … Everything all-inclusive …”

I couldn’t picture it. The images wouldn’t come to me—or rather, they did, but they seemed comic somehow, like it wasn’t really my father but a stand-in, an actor. What came to me more easily was the image of my father in his usual flannel shirt and grubby blue jeans, the old well-worn slippers he plodded around in both inside and out, and the slow dawning of disappointment both he and Barbara would feel in each other as the two of them sat on the bed in their cabin, turning away from each other, realizing too late the mistake they had made in going on this trip together. My father had rarely, if ever, spent a night away from the farm, and I knew—even if he didn’t—that the world beyond the property lines frightened and intimidated him; it contained people who were cruel and judgmental, and this world could best be viewed from the safety of his armchair as it played itself out on television. Ordinarily, my father would have laughed off such an outrageous suggestion—A cruise! You think I’m some kind of big shot?—but my father had changed, I no longer knew him, and I needed to protect him.

“How much is a cruise?” I said, hoping the answer would quickly deflate any notion of embarking on such a doomed voyage.

“Three thousand,” Barbara said, then sheepishly added, “Maybe closer to four.”

“Four thousand!” My father clanked his dessert plate onto the end table. “Oh, no,” he said. “And who’s going to look after the house?”

Barbara seemed stunned by the question. “Well …” she said. “You have neighbours, don’t you? They could look in on the house once in a while. No?”

“Yeah, well …” my father replied, and the rest of the sentence fell away.

An awkward silence settled over the room as the three of us focused on the cake in our laps. When I at last set my empty plate back on the coffee table, I turned to gaze out the picture window at the leaves on the trees, shimmering in the sunny outdoors, and again thought of Michael and whomever he was with, the two of them laughing no doubt at the goings-on onstage, perhaps a hand suddenly reaching out for the other in the dark.

“That was lovely, dear,” Barbara said, laying her empty plate on the coffee table. She brought her hand to her mouth, covering a deep but barely audible rumble of a belch. “Very kind of you. Thank you so much.”

“Is there tennis on TV?” Barbara said, when the silence had stretched into minutes.

“You like tennis?” My father reached for the remot

e and began flicking through the channels.

“Oh, I adore it, dear. We used to play it all the time in the summers, Patrick and I.”

Patrick? Was that her husband’s name? I was certain she had called him Robert. Maybe Patrick was her son. But something about the sound of my voice and its present falseness prevented me from breaking up the silence that had once again enveloped the room. Anyway, what did I care? This woman meant nothing to me and I couldn’t wait for her to go home.

“And you, Bert?” she said. “You like tennis?”

“Ach!” My father waved away the idea. “I don’t care much for sports. I like gardening. And TV. I like the old shows. The Waltons. Little House on the Prairie. Those were the best.”

“Doesn’t look like there’s any tennis on, does it, darling?” she said to me.

“Oh, I like this,” my father said, pausing the clicker on an old western from the eighties.

“And what do you like to do on a Sunday afternoon?” Barbara asked, turning to me suddenly.

“Oh, he’s always got his nose in a book,” my father said, upping the volume on the TV.

Barbara, still gazing at me, smiled. “Patrick was the president of the literary society in town,” she said, seeming to recall a distant memory. “He was a big reader too.”

By this point my father had taken on the trancelike blankness of one absorbed in a movie. I looked up at the clock and tried to think of something to say, and when nothing came to mind I also turned to the TV, as if this were a final and irrevocable act, one I wouldn’t be able to undo once committed. On the screen were two men—one in a bowler, another in a cowboy hat—and a woman in a frilly pink dress typical of the period, the three of them riding in a stagecoach that was under attack by Indians on horseback. With a shower of poison-tipped arrows, the Indians killed the stagecoach driver, leaving the horses to run wild and the stagecoach to go out of control.

“That’s not Roger Moore, is it, darling?” Barbara said. Without turning around I said it wasn’t, though I couldn’t remember the actor’s real name. “I adore Roger Moore,” she said. “Such a handsome man.”

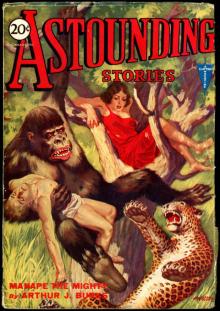

Astounding Stories, March, 1931

Astounding Stories, March, 1931 Astounding Stories, February, 1931

Astounding Stories, February, 1931 Futuria Fantasia, Spring 1940

Futuria Fantasia, Spring 1940 The King's Daughter and Other Stories for Girls

The King's Daughter and Other Stories for Girls Uncanny Tales

Uncanny Tales Masters of Noir: Volume Two

Masters of Noir: Volume Two Witty Pieces by Witty People

Witty Pieces by Witty People Sylvaneth

Sylvaneth Space Wolves

Space Wolves Hammerhal & Other Stories

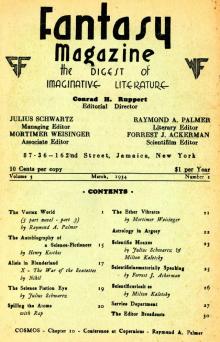

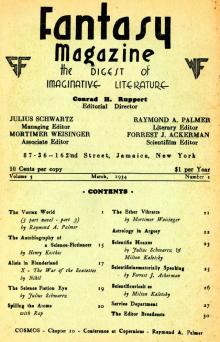

Hammerhal & Other Stories The Fantasy Fan, March, 1934

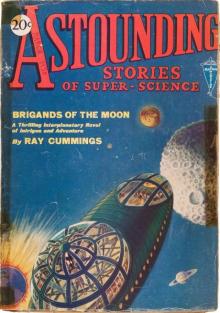

The Fantasy Fan, March, 1934 Astounding Stories of Super-Science, August 1930

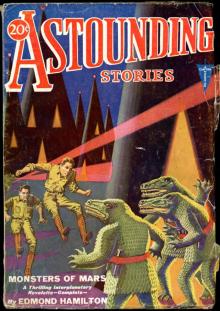

Astounding Stories of Super-Science, August 1930 Astounding Stories, August, 1931

Astounding Stories, August, 1931 The Burden of Loyalty

The Burden of Loyalty Return to Wonderland

Return to Wonderland Anthology - A Thousand Doors

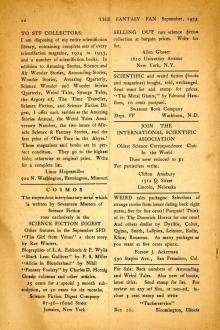

Anthology - A Thousand Doors The Fantasy Fan, October 1933

The Fantasy Fan, October 1933 Astounding Stories, June, 1931

Astounding Stories, June, 1931 Southern Stories

Southern Stories Astounding Stories of Super-Science, May, 1930

Astounding Stories of Super-Science, May, 1930 The Fantasy Fan December 1933

The Fantasy Fan December 1933 Adventures in Many Lands

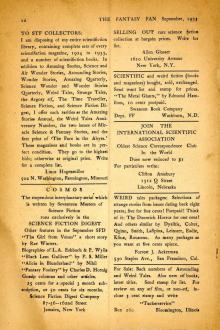

Adventures in Many Lands The Fantasy Fan February 1934

The Fantasy Fan February 1934 The Fantasy Fan November 1933

The Fantasy Fan November 1933 Astounding Stories, April, 1931

Astounding Stories, April, 1931 Fame and Fortune Weekly, No. 801, February 4, 1921

Fame and Fortune Weekly, No. 801, February 4, 1921 Astounding Stories of Super-Science, November, 1930

Astounding Stories of Super-Science, November, 1930 Astounding Stories of Super-Science January 1931

Astounding Stories of Super-Science January 1931 A Monk of Fife

A Monk of Fife Astounding Stories of Super-Science September 1930

Astounding Stories of Super-Science September 1930 Astounding Stories of Super-Science July 1930

Astounding Stories of Super-Science July 1930 Astounding Stories of Super-Science, June, 1930

Astounding Stories of Super-Science, June, 1930 Astounding Stories of Super-Science, October, 1930

Astounding Stories of Super-Science, October, 1930 Astounding Stories of Super-Science, March 1930

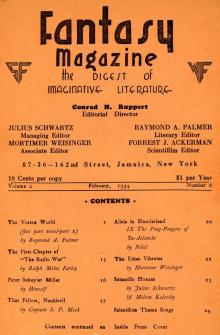

Astounding Stories of Super-Science, March 1930 The Fantasy Fan January 1934

The Fantasy Fan January 1934 The Fantasy Fan September 1933

The Fantasy Fan September 1933 Astounding Stories of Super-Science February 1930

Astounding Stories of Super-Science February 1930 Astounding Stories, May, 1931

Astounding Stories, May, 1931 Strange Stories of Colonial Days

Strange Stories of Colonial Days Golden Age of Science Fiction Vol IX

Golden Age of Science Fiction Vol IX Astounding Stories of Super-Science, December 1930

Astounding Stories of Super-Science, December 1930 Evolutions: Essential Tales of the Halo Universe

Evolutions: Essential Tales of the Halo Universe Good Stories Reprinted from the Ladies' Home Journal of Philadelphia

Good Stories Reprinted from the Ladies' Home Journal of Philadelphia Dragons!

Dragons! Murder Takes a Holiday

Murder Takes a Holiday Legacies of Betrayal

Legacies of Betrayal STAR WARS: TALES FROM THE CLONE WARS

STAR WARS: TALES FROM THE CLONE WARS Strange New Worlds 2016

Strange New Worlds 2016 Lippincott's Magazine, August, 1885

Lippincott's Magazine, August, 1885 Golden Age of Science Fiction Vol X

Golden Age of Science Fiction Vol X Hot Stuff

Hot Stuff Santa Wore Spurs

Santa Wore Spurs Paranormal Erotica

Paranormal Erotica Tangled Hearts: A Menage Collection

Tangled Hearts: A Menage Collection Sweet Tea and Jesus Shoes

Sweet Tea and Jesus Shoes The Journey Prize Stories 25

The Journey Prize Stories 25 Wild Western Tales 2: 101 Classic Western Stories Vol. 2 (Civitas Library Classics)

Wild Western Tales 2: 101 Classic Western Stories Vol. 2 (Civitas Library Classics) (5/15) The Golden Age of Science Fiction Volume V: An Anthology of 50 Short Stories

(5/15) The Golden Age of Science Fiction Volume V: An Anthology of 50 Short Stories (4/15) The Golden Age of Science Fiction Volume IV: An Anthology of 50 Short Stories

(4/15) The Golden Age of Science Fiction Volume IV: An Anthology of 50 Short Stories Ten Journeys

Ten Journeys The Boss

The Boss The Penguin Book of French Poetry

The Penguin Book of French Poetry Golden Age of Science Fiction Vol VIII

Golden Age of Science Fiction Vol VIII His Cinderella Housekeeper 3-in-1

His Cinderella Housekeeper 3-in-1 The Magazine of Fantasy & Science Fiction - July/August 2016

The Magazine of Fantasy & Science Fiction - July/August 2016 PYRATE CTHULHU - Tales of the Cthulhu Mythos (vol.2)

PYRATE CTHULHU - Tales of the Cthulhu Mythos (vol.2) Tales from a Master's Notebook

Tales from a Master's Notebook April 1930

April 1930 New Erotica 6

New Erotica 6 Damocles

Damocles The Longest Night Vol. 1

The Longest Night Vol. 1 The Golden Age of Science Fiction Volume VI: An Anthology of 50 Short Stories

The Golden Age of Science Fiction Volume VI: An Anthology of 50 Short Stories (1/15) The Golden Age of Science Fiction: An Anthology of 50 Short Stories

(1/15) The Golden Age of Science Fiction: An Anthology of 50 Short Stories Eye of Terra

Eye of Terra ONCE UPON A REGENCY CHRISTMAS

ONCE UPON A REGENCY CHRISTMAS Nexus Confessions

Nexus Confessions Passionate Kisses

Passionate Kisses War Without End

War Without End Doctor Who: Time Lord Fairy Tales

Doctor Who: Time Lord Fairy Tales Gotrek and Felix: The Anthology

Gotrek and Felix: The Anthology WESTERN CHRISTMAS PROPOSALS

WESTERN CHRISTMAS PROPOSALS The Journey Prize Stories 27

The Journey Prize Stories 27 The Silent War

The Silent War Liaisons

Liaisons Ellora's Cavemen: Tales from the Temple IV

Ellora's Cavemen: Tales from the Temple IV Ellora's Cavemen: Tales from the Temple II

Ellora's Cavemen: Tales from the Temple II Some of the Best From Tor.com, 2013 Edition: A Tor.Com Original

Some of the Best From Tor.com, 2013 Edition: A Tor.Com Original Urban Occult

Urban Occult Fractures

Fractures The Stories: Five Years of Original Fiction on Tor.com

The Stories: Five Years of Original Fiction on Tor.com The Penguin Book of Modern British Short Stories

The Penguin Book of Modern British Short Stories Mortarch of Night

Mortarch of Night The Portable Nineteenth-Century African American Women Writers

The Portable Nineteenth-Century African American Women Writers The Golden Age of Science Fiction Volume VII: An Anthology of 50 Short Stories

The Golden Age of Science Fiction Volume VII: An Anthology of 50 Short Stories Holy Bible: King James Version, The

Holy Bible: King James Version, The Eight Rooms

Eight Rooms sanguineangels

sanguineangels DarkNightsWithaBillionaireBundle

DarkNightsWithaBillionaireBundle Casserole Diplomacy and Other Stories

Casserole Diplomacy and Other Stories How I Survived My Summer Vacation

How I Survived My Summer Vacation Alfred Hitchcock Presents: 16 Skeletons From My Closet

Alfred Hitchcock Presents: 16 Skeletons From My Closet Lords, Ladies, Butlers and Maids

Lords, Ladies, Butlers and Maids The B4 Leg

The B4 Leg Ellora's Cavemen: Tales from the Temple I

Ellora's Cavemen: Tales from the Temple I 2014 Campbellian Anthology

2014 Campbellian Anthology There Is Only War

There Is Only War Obsidian Alliances

Obsidian Alliances 12 Gifts for Christmas

12 Gifts for Christmas Scary Holiday Tales to Make You Scream

Scary Holiday Tales to Make You Scream 25 For 25

25 For 25 The Plagues of Orath

The Plagues of Orath And Then He Kissed Me

And Then He Kissed Me Star Trek - Gateways 7 - WHAT LAY BEYOND

Star Trek - Gateways 7 - WHAT LAY BEYOND Laugh Your Head Off Again and Again

Laugh Your Head Off Again and Again The Balfour Legacy

The Balfour Legacy Golden Age of Science Fiction Vol XI

Golden Age of Science Fiction Vol XI (3/15) The Golden Age of Science Fiction Volume III: An Anthology of 50 Short Stories

(3/15) The Golden Age of Science Fiction Volume III: An Anthology of 50 Short Stories Shas'o

Shas'o Astounding Science Fiction Stories: An Anthology of 350 Scifi Stories Volume 2 (Halcyon Classics)

Astounding Science Fiction Stories: An Anthology of 350 Scifi Stories Volume 2 (Halcyon Classics) Twists in Time

Twists in Time Meduson

Meduson The Magazine of Fantasy & Science Fiction - August 1980

The Magazine of Fantasy & Science Fiction - August 1980 The Journey Prize Stories 22

The Journey Prize Stories 22 The Book that Made Me

The Book that Made Me Angels of Death Anthology

Angels of Death Anthology Ask the Bones

Ask the Bones Emergence

Emergence Beware the Little White Rabbit

Beware the Little White Rabbit Xcite Delights Book 1

Xcite Delights Book 1 Where flap the tatters of the King

Where flap the tatters of the King The Journey Prize Stories 21

The Journey Prize Stories 21 Tales of the Slayer, Volume II

Tales of the Slayer, Volume II Glass Empires

Glass Empires Golden Age of Science Fiction Vol XII

Golden Age of Science Fiction Vol XII (2/15) The Golden Age of Science Fiction Volume II: An Anthology of 50 Short Stories

(2/15) The Golden Age of Science Fiction Volume II: An Anthology of 50 Short Stories Fairytale Collection

Fairytale Collection Angels!

Angels! Golden Age of Science Fiction Vol XIII

Golden Age of Science Fiction Vol XIII