PYRATE CTHULHU - Tales of the Cthulhu Mythos (vol.2) Read online

Page 16

“Why on Earth would you want to go to a god-forsaken place like this Henderson?” his wealthy friends had asked him once he’d explained what and where it was. “Why not go to Maui, or the Bahamas? You say there’s nothing on Henderson but birds, and you’re not a birder.”

That much was true. Chase Rontgern did not collect bird sightings. Nor was he an especially avid scuba diver. What he did collect was money, and at that he was very good.

For more than two years he had been researching the history of ships that had gone missing in Henderson’s vicinity. Ships that had been blown off course, or had become lost due to navigational error, or had simply foundered in storms. Vessels that disappeared in this part of the Pacific well and truly vanished. No ship that encountered trouble in the azure wasteland could expect help.

Since leaving Mangareva they had seen exactly one other vessel; a big container ship heading for Cape Horn. Most commercial traffic bound from the South Pacific for the Atlantic took the easier, much faster route north to the Panama Canal. As for fishing boats, there were no long-liners here, no purse seiners, because as Captain Santos had pointed out, there were no fish. There were no fish because there was nothing for them to eat. Concerning bottom trawlers—the bottom was three or four kilometers down and unknown. Too deep to trawl safely for too little potential reward for a big dragliner to take the risk.

When Henderson itself finally hove into view days later its appearance was something of an anticlimax. Rontgern was not disillusioned. The reality matched the few pictures he had been able to find of the place. Unlike Bora Bora or Rarotonga, Pacific islands that boasted dramatic central peaks and gleaming turquoise lagoons, Henderson was a makatea island. Several others were scattered around the Pacific; huge blocks of limestone and coral that had been uplifted and exposed to the air when the sea levels had fallen during the last ice age. Not only were they usually devoid of beaches, a visitor could not even walk very easily on a makatea. Rain eroded the limestone into razor-sharp, boot-slicing, flesh-shearing blades and pinnacles of solid rock.

As opposed to animals and humans, certain well-adapted birds and vegetation thrived in the otherwise hostile makatea environment. Shearwaters and noddys, petrels and four species of endemics made their home on Henderson. Its only regular human visitors were Pitcairners who came once or twice a year to collect valuable hardwood like miro for the carvings that constituted a substantial part of their income. Other than that, Henderson had been left to the birds, the crabs, a few lizards, and the ubiquitous Polynesian rat. Except for one rumored spring visible only on the single narrow beach at low tide there was not even any fresh water to be had. Not a good place, Rontgern reflected, on which to be marooned.

But then, he was not interested in spending time on Henderson, however wildly attractive the place might be to the rare visiting scientist.

It was a photograph that had finally brought him to this, one of the most isolated tropical islands on Earth. It was the same photograph that had led him to charter the Repera and its somewhat taciturn but efficient crew. His cultivated friends in New York had been right about one thing: no one anywhere much wanted to go to Henderson. It had taken him months, a lot of searching on the net, and an extensive exchange of querulous emails before he found a captain with a ship willing to travel so far from the bounds of civilization, to waters where no help could be expected in the event of trouble, no passing ship could be hailed for assistance, and there was nothing to see and no one to visit. Happily, in the course of their exchange of emails Salvatore Santos had not pressed his prospective employer for a trip rationale. All that had been necessary was to agree on a price.

Henderson slid past astern, its stark white thirty-meter high cliffs gleaming like chalk in the sun, its population of seabirds forming a flat, hazy gray cloud above the trees as they cherished the one bit of dry land for hundreds of kilometers in every direction. The island was still in view astern when Rontgern checked his GPS one more time, turned to the Captain, and declared with confidence, "This is the place.”

Looking up from the wheel and his bridge instruments, the unshaven Portuguese-Tahitian squinted at his employer. “Here?” He waved a sun-cured hand at the surrounding sea, which obligingly had subsided almost to a flat calm. “You want to drop anchor here?"

Rontgern smirked. He knew something the Captain didn’t know. If his two years of painstaking research was right, he knew something nobody else knew. With the possible exception of the bored astronaut on board the space shuttle who had taken the photograph that the energetic Rontgern had scanned in more detail than anyone at NOAA or NASA.

“Check your depth finder.”

Santos had not bothered to look at that particular readout since leaving Pitcairn. The ocean out here was benthonic, and even this close to Henderson it dropped off sharply into the abyss. Under the circumstances, the Captain showed remarkable aplomb as he checked the relevant monitor and reported.

“What do you know? There is an uneven but largely flat surface thirty meters directly below us. I am assuming it is a seamount. It is very small and at a depth that renders it harmless to passing ships, of which there are not any around here anyway. So it not surprising it is absent from the charts.”

“It’s not all that small.” Having looked forward for so long to springing this knowledge on someone else, Rontgern found that he was enjoying himself immensely. “Not just a seamount.”

Santos eyed him uncertainly. Out of the corner of an eye Rontgern could see several members of the half-dozen strong crew watching the two men from the deck. The Captain finally smiled.

“Ah, I understand now. You are a crazy man. I knew that when you hired me and my boat to bring you all this way. But that didn’t bother me. A man can be as crazy as he like, so long as his money is sane.”

Kneeling, Rontgern opened the small watertight Pelican case that occupied a compartment on the bridge near his feet. It contained none of the expensive camera gear it was designed to coddle and protect. Instead, it was full of envelopes, flash drives, and a laptop computer. Selecting and unsealing one of the envelopes, he removed several glossy 8x10 prints and handed the top one to Santos.

“Have a look at this.”

The Captain examined the photo with fresh interest. “Henderson,” he observed immediately. “Taken from space. View slightly from the south. Even with the clouds, you can’t mistake the shape.”

“Very good.” Rontgern handed him the next picture.

Studying it, Santos frowned. “Henderson again, much closer view.” He tapped the picture with a forefinger. “Here; the water is so clear, you can see a suggestion of the seamount we are over right now.”

Rontgern repressed a knowing smirk as he passed over the third and last picture. “That last one was a blowup, multiple magnification. Here’s a much better one, with the resolution computer and radar-enhanced and corrected for depth, shadow, atmospheric distortion, and other obscuring factors I needn’t go into in detail.”

Santos studied the picture. Looked at it for a long time. Then he handed it back to its owner. “I still think it is nothing but a seamount.”

“Seamounts have broken crowns. Or they’re conical in shape. Or capped with solidified lava, or they sport a sunken lagoon.” He gestured with the photo. “This one is as flat on top as a Los Angeles parking lot. Except for the bumps. Bumps with very distinctive shapes.”

A corner of the Captain’s mouth twitched slightly upward. “You think it is a parking lot?”

Rontgern had to laugh. “I’m not crazy, Salvatore, despite what you might think. Those ‘bumps’ are ships that have gone down here. At least four, maybe as many as ten. Maybe more than that, once we get down there. Two of the four are definitely pre-nineteenth century. You know what that means? Maybe treasure galleons that were sailing back to Spain from the Philippines. Trying to sneak around the Horn instead of sailing to Peru or Panama along routes that were haunted by English privateers like Drake. Before they could rea

ch the Horn they got lost, or slammed into Henderson’s rocks. Most went down to the depths. But a few,” and again he tapped the photo, “a few fetched up here. At a depth reachable with nothing more elaborate than conventional sport diving equipment.” He stared hard as he slipped the pictures back into the envelope. “Put down the anchor.”

Santos hesitated a moment longer. Then he shrugged. “Its your money, Mr Rontgern. You may be right. There may be a ship or two down there. But I no think there any treasure. And even if there is, anything we might find belongs to the British government. Henderson is part of the Pitcairn British Overseas Territory.”

“That’s absolutely correct.” With slow deliberation, Rontgern returned the envelope to the watertight case. “And you can see for yourself how well this part of that territory is policed. Should we find anything we’ll declare it immediately when we return to Mangareva. I’m sure you will be the first to go out of your way to inform the British consul in Papeete about any discoveries we may make.” The Captain pursed his lips. To Rontgern they almost seemed to be moving slowly in and out, in and out, in concert with the Captain’s thoughts. Finally Santos smiled; a broad, wide smile.

Rontgern nodded curtly. He had gambled on just such a reaction. As soon as he had met Santos, he knew it was not much of a gamble. “We understand each other, I think.”

“Perfectly, Mr Rontgern. I will tell Bartolomeo to start readying the scuba gear.”

The water was not just clear: in the absence of microscopic pelagic life and located thousands of kilometers from the nearest source of pollutants, it was virtually transparent. As soon as he hit the water and started down, Rontgern felt as if he were diving in air. The only sound following his entry was the regularity of his respiration and the sporadic mutter of bubbles from the regulator.

As for the questions that had brought him to this isolated corner of the planet, they were answered as soon as he entered the water.

Just by looking down and without the aid of any special equipment he could see the outlines of sunken ships resting atop the seamount thirty meters below. Not only could he see the ships, the water was so clear that he could identify each vessel’s type, condition, approximate age, and a host of other informative factors. Twisting as he slowly descended fins first, he located Santos and gave him the thumbs-up sign. His hair drifting lazily behind him like black seaweed, the Captain nodded and responded in kind.

Inclining his head and body downward, an excited Rontgern accelerated his descent.

Inner exploration of the various shipwrecks and the actual search for treasure and other valuables would take place on future dives, with additional equipment. A thirty-meter descent would require a proper surface interval before the next dive. No matter. Now that his research had been confirmed, he found that he was not impatient. After all, it was not as if they were likely to be interrupted by other divers in the course of their salvage work during the next couple of weeks.

They would remove the most valuable items first, hide them in the Repera’s ballast lockers and elsewhere on the ketch, unload the prizes at night onto the private plane he would charter at Mangareva, and then return here for more. He was not worried about parceling out shares. There should be sufficient booty for all, and he would see to it that enough went to the crew of the ketch so that any notion of, say, tossing him overboard and keeping it all for themselves did not have any reason to get a grip on their thoughts. Besides, he knew more about this place than did any of them. He might know more than they could see. Unless they were utterly stupid, they would want to keep him alive in order to make use of that knowledge.

He was elated to see that there were not two but three galleons— and one ship that despite its state of advanced decrepitude looked decidedly Chinese. A load of Ming porcelain—now that would be a treasure indeed! As for the other, more recent shipwrecks, they could hold all manner of lucrative cargo. But it was the prospect of finding older vessels that had drawn him here, and it was those antique craft that understandably now captured the greater part of his interest.

One galleon in particular seemed to be in much better shape than the others. Unfortunately, it teetered on the steep-sided edge of the seamount. Even at this depth there was the danger that a particularly strong storm surge might send it toppling over into unreachable depths. He reassured himself that since it had laid thus for hundreds of years he was probably worrying unnecessarily. Signaling to Santos and to the other diver who was accompanying them, he finned off in the direction of the precariously balanced vessel.

It would be all right, he saw as he began to circle it. Its position was more stable than he had first surmised. Though lying at a sharp angle on its port side, the keel was jammed firmly against a long, narrow ridge of rock that protruded from the top of the seamount. Swimming parallel to the bottom, he swam from the bow toward the stern. Off to his right the ocean dropped away to cold, dark depths unknown.

Strange rock formation, he decided. It almost looked as if it could have been carved. That was impossible, of course. It was simply a natural limestone or lava ridge that had eroded away to form an unusually straight bulwark atop the rest of the underlying rock. He remained convinced of that until he reached the stern of the galleon. Hovering there, he was able to read the name below the great cabin: Santa Isabella de Castillo. Researching that name once he was back on dry land would likely tell him the ship’s history and the cargo she had been carrying on her last, ill-fated voyage.

Something else at the stern caught his eye. More rock, mounded up to form a V-shaped fissure. The stern of the galleon had been wedged directly into this crevice.

How could that have happened, he wondered? It seemed too perfect, too unnaturally precise a fit to be a consequence of the unruly action of wind and wave and current. Still, it was not an impossible coincidence. Storm-driven sub-surface currents could certainly have slammed the ship hard into such a pocket of waiting rock.

It was when he saw the second galleon, and soon afterward the first steamship, jammed stern-first into exactly identical crevices that his thoughts began wandering to places that had nothing to do with treasure salvage, archeology, or the conventional history of South Pacific exploration.

Spinning around in the water, he saw that Santos had come up very close behind him. Gesturing at the third wedged ship, Rontgern formed a vee-shape with his hands, gestured at the vessel, and pushed his chin toward the vee. Santos nodded to show that he immediately grasped what the other man was striving to convey. By way of further response he gestured downward, over the side of the seamount, and indicated that Rontgern should follow. Thoughts churning, the bemused entrepreneur started to comply, but a check of his air dissuaded him. They had been exploring at depth for a substantial period of time. He had just enough air left in his tank to manage a proper slow, safe ascent coupled with a conservative safety stop at five meters.

Hovering over the side of the seamount, however, Santos kept gesturing for Rontgern to follow him downward. Rontgern shook his head. No doubt a better, more experienced diver than the Manhattan-bound entrepreneur, the Captain would naturally have used less air and would have more remaining, as would the deckhand who accompanied them. A cautious Rontgern saw that the other man was excited. Reluctantly, he kicked away from the stern of the sunken steamship and followed the Portuguese to the edge, wondering what was so important that the Captain felt the need to emphasize it so close to the end of the first of what would be many dives.

Instead of pausing to wait for him, Captain and crewman promptly lowered their heads—and started to swim straight down.

Rontgern immediately held back. What was wrong with them? Were they suffering from a combination of exhilaration and nitrogen narcosis? Had they lost their bearings, control of their senses? He hovered in open water at the edge of the seamount as the two divers continued their rapid and inexplicable descent. If they went much deeper they would find themselves in real danger no matter how much air they had left.

&n

bsp; That was when Rontgern saw that something was coming up out of the abyss.

At first he thought his eyes were playing tricks on him. It was no stretch of the imagination to envision something like that occurring at this depth, even in absolutely clear water. Weaving and working its way downward, unobstructed sunlight wove lazily intertwining patterns in the open water column. As Rontgern stared, wide-eyed, some of the patterns began to darken. Each rising shape slowly became something solid. Each was individually as big as the sunken steamship. Independent of the light that illuminated them, they writhed and twisted and coiled expectantly in the transparent, pellucid liquid. Splotches and dark streaks grew visible on the side of each...

Tentacle.

Expelling bubbles in a violent, explosive stream, Rontgern started kicking for the surface. Santos and his companion were forgotten. If luck held, their presence might be enough to divert the ascending monster away from Rontgern. Architeuthis, he thought wildly as he swam for the surface. Giant squid. Or perhaps the fabled Colossal squid, slithered up from the Antarctic to graze on passing whales. Rontgern kicked as he had never kicked in his life.

He had no choice but to pause at five meters and decompress. If he did not outgas the nitrogen bubbles that had accumulated in his bloodstream, the bends would kill him as surely and as painfully as any sea monster. He forced himself not to look down, not to seek for what even now might be reaching up for him. If it came for him, better that his last conscious view was not one of hooked, flesh-ripping suckers and sharp slicing beak. Taken by the kraken, he thought wildly. What an end for a wily double-dealer from New York.

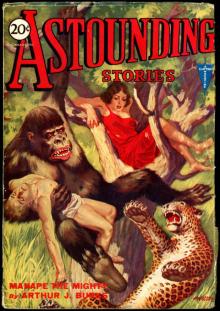

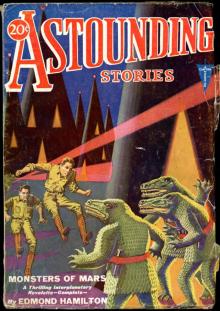

Astounding Stories, March, 1931

Astounding Stories, March, 1931 Astounding Stories, February, 1931

Astounding Stories, February, 1931 Futuria Fantasia, Spring 1940

Futuria Fantasia, Spring 1940 The King's Daughter and Other Stories for Girls

The King's Daughter and Other Stories for Girls Uncanny Tales

Uncanny Tales Masters of Noir: Volume Two

Masters of Noir: Volume Two Witty Pieces by Witty People

Witty Pieces by Witty People Sylvaneth

Sylvaneth Space Wolves

Space Wolves Hammerhal & Other Stories

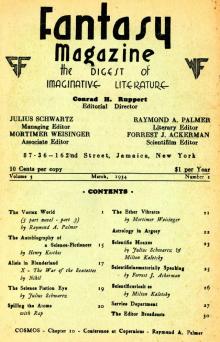

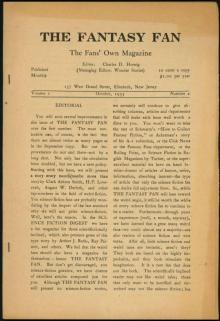

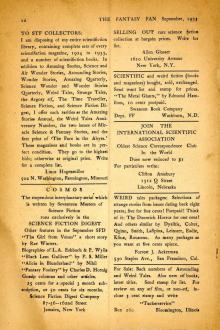

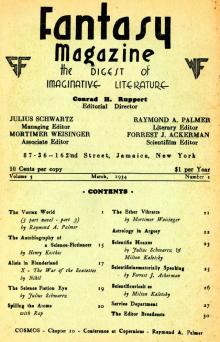

Hammerhal & Other Stories The Fantasy Fan, March, 1934

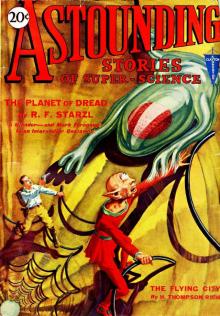

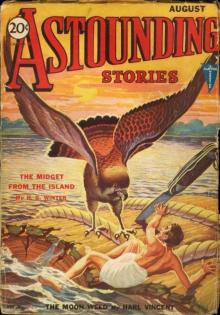

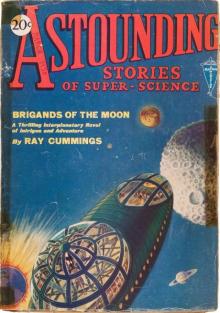

The Fantasy Fan, March, 1934 Astounding Stories of Super-Science, August 1930

Astounding Stories of Super-Science, August 1930 Astounding Stories, August, 1931

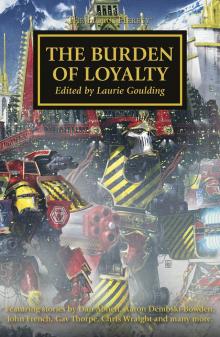

Astounding Stories, August, 1931 The Burden of Loyalty

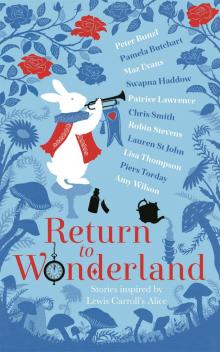

The Burden of Loyalty Return to Wonderland

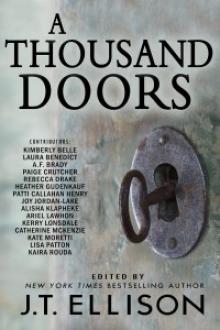

Return to Wonderland Anthology - A Thousand Doors

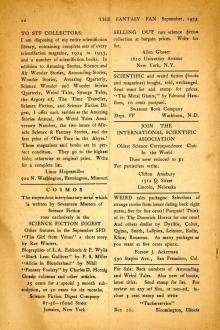

Anthology - A Thousand Doors The Fantasy Fan, October 1933

The Fantasy Fan, October 1933 Astounding Stories, June, 1931

Astounding Stories, June, 1931 Southern Stories

Southern Stories Astounding Stories of Super-Science, May, 1930

Astounding Stories of Super-Science, May, 1930 The Fantasy Fan December 1933

The Fantasy Fan December 1933 Adventures in Many Lands

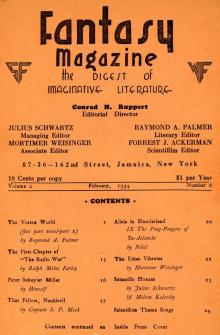

Adventures in Many Lands The Fantasy Fan February 1934

The Fantasy Fan February 1934 The Fantasy Fan November 1933

The Fantasy Fan November 1933 Astounding Stories, April, 1931

Astounding Stories, April, 1931 Fame and Fortune Weekly, No. 801, February 4, 1921

Fame and Fortune Weekly, No. 801, February 4, 1921 Astounding Stories of Super-Science, November, 1930

Astounding Stories of Super-Science, November, 1930 Astounding Stories of Super-Science January 1931

Astounding Stories of Super-Science January 1931 A Monk of Fife

A Monk of Fife Astounding Stories of Super-Science September 1930

Astounding Stories of Super-Science September 1930 Astounding Stories of Super-Science July 1930

Astounding Stories of Super-Science July 1930 Astounding Stories of Super-Science, June, 1930

Astounding Stories of Super-Science, June, 1930 Astounding Stories of Super-Science, October, 1930

Astounding Stories of Super-Science, October, 1930 Astounding Stories of Super-Science, March 1930

Astounding Stories of Super-Science, March 1930 The Fantasy Fan January 1934

The Fantasy Fan January 1934 The Fantasy Fan September 1933

The Fantasy Fan September 1933 Astounding Stories of Super-Science February 1930

Astounding Stories of Super-Science February 1930 Astounding Stories, May, 1931

Astounding Stories, May, 1931 Strange Stories of Colonial Days

Strange Stories of Colonial Days Golden Age of Science Fiction Vol IX

Golden Age of Science Fiction Vol IX Astounding Stories of Super-Science, December 1930

Astounding Stories of Super-Science, December 1930 Evolutions: Essential Tales of the Halo Universe

Evolutions: Essential Tales of the Halo Universe Good Stories Reprinted from the Ladies' Home Journal of Philadelphia

Good Stories Reprinted from the Ladies' Home Journal of Philadelphia Dragons!

Dragons! Murder Takes a Holiday

Murder Takes a Holiday Legacies of Betrayal

Legacies of Betrayal STAR WARS: TALES FROM THE CLONE WARS

STAR WARS: TALES FROM THE CLONE WARS Strange New Worlds 2016

Strange New Worlds 2016 Lippincott's Magazine, August, 1885

Lippincott's Magazine, August, 1885 Golden Age of Science Fiction Vol X

Golden Age of Science Fiction Vol X Hot Stuff

Hot Stuff Santa Wore Spurs

Santa Wore Spurs Paranormal Erotica

Paranormal Erotica Tangled Hearts: A Menage Collection

Tangled Hearts: A Menage Collection Sweet Tea and Jesus Shoes

Sweet Tea and Jesus Shoes The Journey Prize Stories 25

The Journey Prize Stories 25 Wild Western Tales 2: 101 Classic Western Stories Vol. 2 (Civitas Library Classics)

Wild Western Tales 2: 101 Classic Western Stories Vol. 2 (Civitas Library Classics) (5/15) The Golden Age of Science Fiction Volume V: An Anthology of 50 Short Stories

(5/15) The Golden Age of Science Fiction Volume V: An Anthology of 50 Short Stories (4/15) The Golden Age of Science Fiction Volume IV: An Anthology of 50 Short Stories

(4/15) The Golden Age of Science Fiction Volume IV: An Anthology of 50 Short Stories Ten Journeys

Ten Journeys The Boss

The Boss The Penguin Book of French Poetry

The Penguin Book of French Poetry Golden Age of Science Fiction Vol VIII

Golden Age of Science Fiction Vol VIII His Cinderella Housekeeper 3-in-1

His Cinderella Housekeeper 3-in-1 The Magazine of Fantasy & Science Fiction - July/August 2016

The Magazine of Fantasy & Science Fiction - July/August 2016 PYRATE CTHULHU - Tales of the Cthulhu Mythos (vol.2)

PYRATE CTHULHU - Tales of the Cthulhu Mythos (vol.2) Tales from a Master's Notebook

Tales from a Master's Notebook April 1930

April 1930 New Erotica 6

New Erotica 6 Damocles

Damocles The Longest Night Vol. 1

The Longest Night Vol. 1 The Golden Age of Science Fiction Volume VI: An Anthology of 50 Short Stories

The Golden Age of Science Fiction Volume VI: An Anthology of 50 Short Stories (1/15) The Golden Age of Science Fiction: An Anthology of 50 Short Stories

(1/15) The Golden Age of Science Fiction: An Anthology of 50 Short Stories Eye of Terra

Eye of Terra ONCE UPON A REGENCY CHRISTMAS

ONCE UPON A REGENCY CHRISTMAS Nexus Confessions

Nexus Confessions Passionate Kisses

Passionate Kisses War Without End

War Without End Doctor Who: Time Lord Fairy Tales

Doctor Who: Time Lord Fairy Tales Gotrek and Felix: The Anthology

Gotrek and Felix: The Anthology WESTERN CHRISTMAS PROPOSALS

WESTERN CHRISTMAS PROPOSALS The Journey Prize Stories 27

The Journey Prize Stories 27 The Silent War

The Silent War Liaisons

Liaisons Ellora's Cavemen: Tales from the Temple IV

Ellora's Cavemen: Tales from the Temple IV Ellora's Cavemen: Tales from the Temple II

Ellora's Cavemen: Tales from the Temple II Some of the Best From Tor.com, 2013 Edition: A Tor.Com Original

Some of the Best From Tor.com, 2013 Edition: A Tor.Com Original Urban Occult

Urban Occult Fractures

Fractures The Stories: Five Years of Original Fiction on Tor.com

The Stories: Five Years of Original Fiction on Tor.com The Penguin Book of Modern British Short Stories

The Penguin Book of Modern British Short Stories Mortarch of Night

Mortarch of Night The Portable Nineteenth-Century African American Women Writers

The Portable Nineteenth-Century African American Women Writers The Golden Age of Science Fiction Volume VII: An Anthology of 50 Short Stories

The Golden Age of Science Fiction Volume VII: An Anthology of 50 Short Stories Holy Bible: King James Version, The

Holy Bible: King James Version, The Eight Rooms

Eight Rooms sanguineangels

sanguineangels DarkNightsWithaBillionaireBundle

DarkNightsWithaBillionaireBundle Casserole Diplomacy and Other Stories

Casserole Diplomacy and Other Stories How I Survived My Summer Vacation

How I Survived My Summer Vacation Alfred Hitchcock Presents: 16 Skeletons From My Closet

Alfred Hitchcock Presents: 16 Skeletons From My Closet Lords, Ladies, Butlers and Maids

Lords, Ladies, Butlers and Maids The B4 Leg

The B4 Leg Ellora's Cavemen: Tales from the Temple I

Ellora's Cavemen: Tales from the Temple I 2014 Campbellian Anthology

2014 Campbellian Anthology There Is Only War

There Is Only War Obsidian Alliances

Obsidian Alliances 12 Gifts for Christmas

12 Gifts for Christmas Scary Holiday Tales to Make You Scream

Scary Holiday Tales to Make You Scream 25 For 25

25 For 25 The Plagues of Orath

The Plagues of Orath And Then He Kissed Me

And Then He Kissed Me Star Trek - Gateways 7 - WHAT LAY BEYOND

Star Trek - Gateways 7 - WHAT LAY BEYOND Laugh Your Head Off Again and Again

Laugh Your Head Off Again and Again The Balfour Legacy

The Balfour Legacy Golden Age of Science Fiction Vol XI

Golden Age of Science Fiction Vol XI (3/15) The Golden Age of Science Fiction Volume III: An Anthology of 50 Short Stories

(3/15) The Golden Age of Science Fiction Volume III: An Anthology of 50 Short Stories Shas'o

Shas'o Astounding Science Fiction Stories: An Anthology of 350 Scifi Stories Volume 2 (Halcyon Classics)

Astounding Science Fiction Stories: An Anthology of 350 Scifi Stories Volume 2 (Halcyon Classics) Twists in Time

Twists in Time Meduson

Meduson The Magazine of Fantasy & Science Fiction - August 1980

The Magazine of Fantasy & Science Fiction - August 1980 The Journey Prize Stories 22

The Journey Prize Stories 22 The Book that Made Me

The Book that Made Me Angels of Death Anthology

Angels of Death Anthology Ask the Bones

Ask the Bones Emergence

Emergence Beware the Little White Rabbit

Beware the Little White Rabbit Xcite Delights Book 1

Xcite Delights Book 1 Where flap the tatters of the King

Where flap the tatters of the King The Journey Prize Stories 21

The Journey Prize Stories 21 Tales of the Slayer, Volume II

Tales of the Slayer, Volume II Glass Empires

Glass Empires Golden Age of Science Fiction Vol XII

Golden Age of Science Fiction Vol XII (2/15) The Golden Age of Science Fiction Volume II: An Anthology of 50 Short Stories

(2/15) The Golden Age of Science Fiction Volume II: An Anthology of 50 Short Stories Fairytale Collection

Fairytale Collection Angels!

Angels! Golden Age of Science Fiction Vol XIII

Golden Age of Science Fiction Vol XIII