April 1930 Read online

Page 2

"So we made our plans," he went on, pleased with our discomfiture and our despising of him. "Next day some chap came to see me, pretending he was my brother. And I carried out my part of it by cursing him at first and then begging him to give me decent burial. So he went away, and, I suppose, received permission to get me right after I was cut down.

"There was a fence built around the scaffold they had ready for me and the party I was about to fling, and they had some militia there, too. The crowd seemed quiet enough till they led me out. Then their buzzing sounded like a hive of bees getting all stirred up. Then a few loud voices, then shouts. Some rocks came flying at me after that, and it looked to me as though the hanging would not be so gentle a party after all. I tell you I was afraid. I wished it was over.

* * * * *

"The mob pushed against the fence and flattened it out, coming over it like waves over a beach. The soldiers fired into the air, but still they came, and I, I ran--up, onto the scaffold. It was safer!" As he said this he chuckled loudly. "I'll bet," he laughed, "that's the first time a guy ever ran into the noose for the safety of it! The mob came only to the foot of the scaffold though, from where they seemed satisfied to see the law take its course. The sheriff was nervous. So cut up that he only made a fling at tying my ankles, just dropped a rope around my wrists. He was like me, he wanted to get it over, and the crowd on its way. Then he put the rope around my neck, stepped back and shot the trap. Zamm! No time for a prayer--or for me to laugh at the offer!--or a last word or anything.

"I felt the floor give, felt myself shoot through. Smack! My weight on the end of the rope hit me behind the ears like a mallet. Everything went black. Of course it would have been just my luck to get a broken neck out of it and give the scientist no chance to revive me. But after a second or two, or a minute, or it could have been an hour, the blackness went away enough to allow me to know I was hanging on the end of the rope, kicking, fighting, choking to death. My tongue swelled, my face and head and heart and body seemed ready to burst. Slowly I went into a deep mist that I knew then was the mist, then--then--I was off floating in the air over the heads of the crowd, watching my own hanging!

"I saw them give that slowly swinging carcass on the end of its rope time enough to thoroughly die, then, from my aerial, unseen watching place, I saw them cut it--me--down. They tried the pulse of the body that had been mine, they examined my staring eyes. Then I heard them pronounce me dead. The fools! I had known I was dead for a minute or two by that time, else how could my spirit have been gone from the shell and be out floating around over their heads?"

* * * * *

He paused here as he asked his question, his head turning on its dry and creaking neck to include us all in his query. But none of us spoke. We were dreaming it all, of course, or were mad, we thought.

"In just a short while," went on the skeleton, "my 'brother' came driving slowly in for my body. With no special hurry he loaded me onto his little truck and drove easily away. But once clear of the crowd he pushed his foot down on the gas and in five more minutes--with me hovering all the while alongside of him, mind you--floating along as though I had been a bird all my life--we turned into the driveway of a summer home. The scientific guy met him. They carried me into the house, into a fine-fitted laboratory. My dead body was placed on a table, a huge knife ripped my clothes from me.

"Quickly the loads from ten or a dozen hypodermic syringes were shot into different parts of my naked body. Then it was carried across the room to what looked like a large glass bottle, or vase, with an opening in the top. Through this door I was lowered, my body being held upright by straps in there for that purpose. The door to the opening was then placed in position, and by means of an acetylene torch and some easily melting glass, the door was sealed tight.

"So there stood my poor old body. Ready for the experiment to bring it back to life. And as my new self floated around above the scientist and his helper I smiled to myself, for I was sure the experiment would prove a failure, even though I now knew that the sheriff's haste had kept him from placing the rope right at my throat and had saved me a broken neck. I was dead. All that was left of me now was my spirit, or soul. And that was swimming and floating about above their heads with not an inclination in the world to have a thing to do with the husk of the man I could clearly see through the glass of the bell.

* * * * *

"They turned on a huge battery of ultra-violet rays then," continued the hollow droning of the man who had been hanged, "which, as the scientist had explained to me while in prison, acting upon the contents of the syringes, by that time scattered through my whole body, was to renew the spark of life within the dead thing hanging there. Through a tube, and by means of a valve entering the glass vase in the top, the scientist then admitted a dense white gas. So thick was it that in a moment or two my body's transparent coffin appeared to be full of a liquid as white as milk. Electricity then revolved my cage around so that my body was insured a complete and even exposure to the rays of the green and violet lamps. And while all this silly stuff was going on, around and around the laboratory I floated, confident of the complete failure of the whole thing, yet determined to see it through if for no other reason than to see the discomfiture and disappointment that this mere man was bound to experience. You see, I was already looking back upon earthly mortals as being inferior, and now as I waited for this proof I was all the while fighting off a new urge to be going elsewhere. Something was calling me, beckoning me to be coming into the full spirit world. But I wanted to see this wise earth guy fail.

"For a little while conditions stayed the same within that glass. So thick was the liquid gas in there at first that I could see nothing. Then it began to clear, and I saw to my surprise that the milky gas was disappearing because it was being forced in by the rays from the lights in through the pores into the body itself. As though my form was sucking it in like a sponge. The scientist and his helper were tense and taut with excitement. And suddenly my comfortable feeling left me. Until then it had seemed so smooth and velvety and peaceful drifting around over their heads, as though lying on a soft, fleecy cloud. But now I felt a sudden squeezing of my spirit body. Then I was in an agony. Before I knew what I was doing my spirit was clinging to the outside of that twisting glass bell, clawing to get into the body that was coming back to life! The glass now was perfectly clear of the gas, though as yet there was no sign of life in the body inside to hint to the scientist that he was to be successful. But I knew it. For I fought desperately to break in through the glass to get back into my discarded shell of a body again, knowing I must get in or die a worse death than I had before.

"Then my sharper eyes noted a slight shiver passing over the white thing before me, and the scientist must have seen it in the next second, for he sprang forward with a choking cry of delight. Then the lolling head inside lifted a bit. I--still desperately clinging with my spirit hands to the outside, and all the time growing weaker and weaker--I saw the breast of my body rise and fall. The assistant picked up a heavy steel hammer and stood ready to crash open the glass at the right moment. Then my once dead eyes opened in there to look around, while I, clinging and gasping outside, just as I had on the scaffold, went into a deeper, darker blackness than ever. Just before my spirit life died utterly I saw the eyes of my body realize completely what was going on, then--from the inside now--I saw the scientist give the signal that caused the assistant to crash away the glass shell with one blow of his hammer.

"They reached in for me then, and I fainted. When I came back to consciousness I was being carefully, slowly revived, and nursed back to life by oxygen and a pulmotor."

* * * * *

The terrible creature telling us this tale paused again to look around. My knees were weak, my clothes wet with sweat.

"Is that all?" I asked in a piping, strange voice, half sarcastic, half unbelieving, and wholly spellbound.

"Just about," he answered. "But what do you expect? I left my friend

the scientist at once, even though he did hate to see me go. It had been all right while he was so keen on the experiment himself and while he only half believed his ability to bring me back. But now that he'd done it, it kinda worried him to think what sort of a man he was turning loose of the world again. I could see how he was figuring, and because I had no idea of letting him try another experiment on me, p'r'aps of putting me away again, I beat it in a hurry.

"That was five years ago. For five years I've lived with only just part of me here. Whatever it was trying to get back into that glass just before my body came to life--my spirit, I've been calling it--I've been without. It never did get back. You see, the scientist brought me back inside a shell that kept my spirit out. That's why I'm the skeleton you see I am. Something vital is missing."

He stood up cracking and creaking before us, buttoning his loose coat about his angular body. "Well, boys," he asked lightly, "what do you think of that?"

"I think you're a liar! A damn liar!" I cried. "And now, if you don't want me to fill you full of lead, get out of here and get out now! If I have to do it to you, there's no scientist this time to bring you back. When you go out you'll stay out!"

"Don't worry," he grimaced back to me, waving a mass of bones that should have been a hand contemptuously at me, "I'm going. I'm headed for Shelton." He stalked the length of the floor and shut the door behind him. The beast had gone.

"The dirty liar!" I cried. "I wish--yes--I wish I had an excuse to kill him. Just think of that being loose, will you? A brute who would think up such a yarn! Of course it's all absurd. All crazy. All a lie."

"No. It's not a lie."

* * * * *

I turned to see who had spoken. Hammersly's voice was so unfamiliar and now so torn in addition that I could not have thought he had spoken, had he not been looking right at me, his glittering eyes challenging my assertion. Would wonders never cease? I asked myself. First this outrageous yarn, now Hammersly, the "sphinx," expressing an opinion, looking for an argument! Of course it must be that his susceptible and brooding brain had been turned a bit by the evening we had just experienced.

"Why Hammersly! You don't believe it?" I asked.

"I not only believe it, Jerry, but now it's my turn to say, as he did, I know it! Jerry, old friend," he went on, "that devil told the truth. He was hanged. He was brought back to life; and Jerry--I was that scientist!"

Whew! I fell back to a box again. My knees seemed to forsake me. Then I heard Hammersly talking to himself.

"Five years it's been," he muttered. "Five years since I turned him loose again. Five years of agony for me, wondering what new devilish crimes he was perpetrating, wondering when he would return to that little farm to swing his ax again. Five years--five years."

He came over to me, and without a word of explanation or to ask my permission he reached his hand into my pocket and drew out my revolver, and I did not protest.

"He said he was headed for Shelton," went on Hammersly's spoken thoughts. "If I slip across the ice I can intercept him at Black's woods." Buttoning his coat closely, he followed the stranger out into the night.

* * * * *

I was glad the moon had come up for my walk home, glad too when I had the door locked and propped with a chair behind me. I undressed in the dark, not wanting any grisly, sunken-eyed monster to be looking in through the window at me. For maybe, so I thought, maybe he was after all not headed for Shelton, but perhaps planning on another of his ghastly tricks.

But in the morning we knew he had been going toward Shelton. Scientists, doctors, and learned men of all descriptions came out to our village to see the thing the papers said Si Waters had stumbled upon when on his way to the creamery that next morning.

It was a skeleton, they said, only that it had a dry skin all over it. A mummy. Could not have been considered capable of containing life only that the snow around it was lightly blotched with a pale smear that proved to be blood, that had oozed out from the six bullet holes in the horrid chest. They never did solve it.

There were five of us in the store that night. Five of us who know. Hammersly did what we all wanted to do. Of course his name is not really Hammersly, but it has done here as well as another. He is black-whiskered though, and he is still very much of a sphinx, but he'll never have to answer for having killed the man he once brought back to life. Hammersly's secret will go into five other graves besides his own.

Monsters of Moyen

By Arthur J. Burks

"The Western World shall be next!" was the dread ultimatum of the half-monster, half-god Moyen!

Foreword

In 1935 the mighty genius of Moyen gripped the Eastern world like a hand of steel. In a matter of months he had welded the Orient into an unbeatable war-machine. He had, through the sheer magnetism of a strange personality, carried the Eastern world with him on his march to conquest of the earth, and men followed him with blind faith as men in the past have followed the banners of the Thaumaturgists.

A strange name, to the sound of which none could assign nationality. Some said his father was a Russian refugee, his mother a Mongol woman. Some said he was the son of a Caucasian woman lost in the Gobi and rescued by a mad lama of Tibet, who became father of Moyen. Some said that his mother was a goddess, his father a fiend out of hell.

But this all men knew about him: that he combined within himself the courage of a Hannibal, the military genius of a Napoleon, the ideals of a Sun Yat Sen; and that he had sworn to himself he would never rest until the earth was peopled by a single nation, with Moyen himself in the seat of the mighty ruler.

Madagascar was the seat of his government, from which he looked across into United Africa, the first to join his confederacy. The Orient was a dependency, even to that forbidden land of the Goloks, where outlanders sometimes went, but whence they never returned--and to the wild Goloks he was a god whose will was absolute, to render obedience to whom was a privilege accorded only to the Chosen.

* * * * *

In a short year his confederacy had brought under his might the millions of Asia, which he had welded into a mighty machine for further conquest.

And because the Americas saw the handwriting on the wall, they sent out to see the man Moyen, with orders to penetrate to his very side, as a spy, their most trusted Secret Agent--Prester Kleig.

Only the ignorant believed that Moyen was mad. The military and diplomatic geniuses of the world recognized his genius, and resented it.

But Prester Kleig, of the Secret Service of the Americas, one of the few men whose headquarters were in the Secret Room in Washington, had reached Moyen.

Now he was coming home.

He came home to tell his people what Moyen was planning, and to admit that his investigations had been hampered at every turn by the uncanny genius of Moyen. Military plans had been guarded with unbelievable secrecy. War machines he knew to exist, yet had seen only those common to all the armies of the world.

And now, twenty-four hours out of New York City, aboard the S. S. Stellar, Prester Kleig was literally willing the steamer to greater speed--and in far Madagascar the strange man called Moyen had given the ultimatum:

"The Western World shall be next!"

CHAPTER I - The Hand of Moyen.

"Who is that man?" asked a young lady passenger of the steward, with the imperious inflection which tells of riches able to force obedience from menials who labor for hire.

She pointed a bejeweled finger at the slender, soldierly figure which stood in the prow of the liner, like a figurehead, peering into the storm under the vessel's forefoot.

"That gentleman, milady?" repeated the steward obsequiously. "That is Prester Kleig, head of the Secret Agents, Master of the Secret Room, just now returning from Madagascar, via Europe, after a visit to the realm of Moyen."

A gasp of terror burst from the lips of the woman. Her cheeks blanched.

"Moyen!" She almost whispered it. "Moyen! The half-god of Asia, whom men call mad!"

But the young lady was not listening to stewards. Wealthy young ladies did not, save when asked questions dealing with personal service to themselves. Her eyes devoured the slender man who stood in the prow of the Stellar, while her lips shaped, over and over again, the dread name which was on the lips of the people of the world:

"Moyen! Moyen!"

* * * * *

Up in the prow, if Prester Kleig, who carried a dread secret in his breast, knew of the young lady's regard, he gave no sign. There were touches of gray at his temples, though he was still under forty. He had seen more of life, knew more of its terrors, than most men twice his age--because he had lived harshly in service to his country.

He was thinking of Moyen, the genius of the misshapen body, the pale eyes which reflected the fires of a Satanic soul, set deeply in the midst of the face of an angel; and wondering if he would be able to arrive in time, sorry that he had not returned home by airplane.

He had taken the Stellar only because the peacefulness of ocean liner travel would aid his thoughts, and he required time to marshal them. Liner travel was now a luxury, as all save the immensely wealthy traveled by plane across the oceans. Now Prester Kleig was sorry, for any moment, he felt, Moyen might strike.

He turned and looked back along the deck of the Stellar. His eyes played over the trimly gowned figure of the woman who questioned the steward, but did not really see her. And then....

"Great God!" The words were a prayer, and they burst from the lips of Prester Kleig like an explosion. Passengers appeared from the lee of lifeboats. Officers on the bridge whirled to look at the man who shouted. Seamen paused in their labors to stare. Aloft in the crow's-nest the lookout lowered his eyes from scouring the horizon to stare at Prester Kleig--who was pointing.

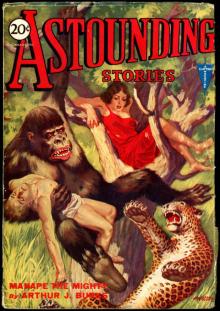

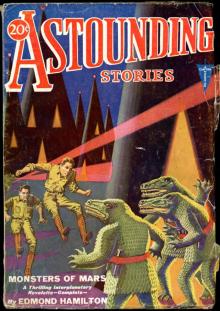

Astounding Stories, March, 1931

Astounding Stories, March, 1931 Astounding Stories, February, 1931

Astounding Stories, February, 1931 Futuria Fantasia, Spring 1940

Futuria Fantasia, Spring 1940 The King's Daughter and Other Stories for Girls

The King's Daughter and Other Stories for Girls Uncanny Tales

Uncanny Tales Masters of Noir: Volume Two

Masters of Noir: Volume Two Witty Pieces by Witty People

Witty Pieces by Witty People Sylvaneth

Sylvaneth Space Wolves

Space Wolves Hammerhal & Other Stories

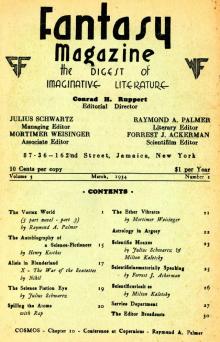

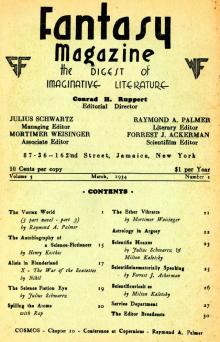

Hammerhal & Other Stories The Fantasy Fan, March, 1934

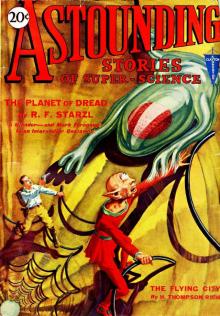

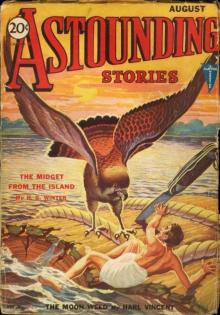

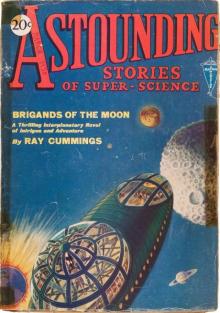

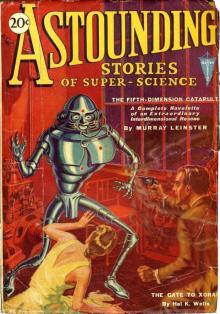

The Fantasy Fan, March, 1934 Astounding Stories of Super-Science, August 1930

Astounding Stories of Super-Science, August 1930 Astounding Stories, August, 1931

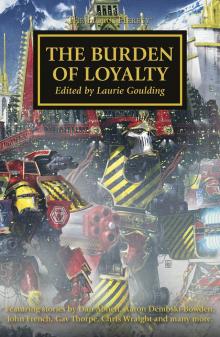

Astounding Stories, August, 1931 The Burden of Loyalty

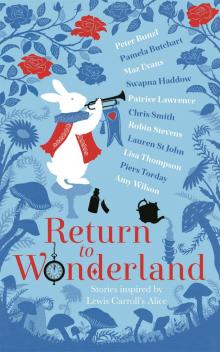

The Burden of Loyalty Return to Wonderland

Return to Wonderland Anthology - A Thousand Doors

Anthology - A Thousand Doors The Fantasy Fan, October 1933

The Fantasy Fan, October 1933 Astounding Stories, June, 1931

Astounding Stories, June, 1931 Southern Stories

Southern Stories Astounding Stories of Super-Science, May, 1930

Astounding Stories of Super-Science, May, 1930 The Fantasy Fan December 1933

The Fantasy Fan December 1933 Adventures in Many Lands

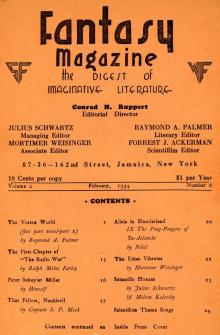

Adventures in Many Lands The Fantasy Fan February 1934

The Fantasy Fan February 1934 The Fantasy Fan November 1933

The Fantasy Fan November 1933 Astounding Stories, April, 1931

Astounding Stories, April, 1931 Fame and Fortune Weekly, No. 801, February 4, 1921

Fame and Fortune Weekly, No. 801, February 4, 1921 Astounding Stories of Super-Science, November, 1930

Astounding Stories of Super-Science, November, 1930 Astounding Stories of Super-Science January 1931

Astounding Stories of Super-Science January 1931 A Monk of Fife

A Monk of Fife Astounding Stories of Super-Science September 1930

Astounding Stories of Super-Science September 1930 Astounding Stories of Super-Science July 1930

Astounding Stories of Super-Science July 1930 Astounding Stories of Super-Science, June, 1930

Astounding Stories of Super-Science, June, 1930 Astounding Stories of Super-Science, October, 1930

Astounding Stories of Super-Science, October, 1930 Astounding Stories of Super-Science, March 1930

Astounding Stories of Super-Science, March 1930 The Fantasy Fan January 1934

The Fantasy Fan January 1934 The Fantasy Fan September 1933

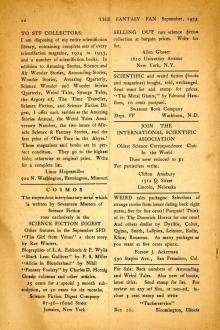

The Fantasy Fan September 1933 Astounding Stories of Super-Science February 1930

Astounding Stories of Super-Science February 1930 Astounding Stories, May, 1931

Astounding Stories, May, 1931 Strange Stories of Colonial Days

Strange Stories of Colonial Days Golden Age of Science Fiction Vol IX

Golden Age of Science Fiction Vol IX Astounding Stories of Super-Science, December 1930

Astounding Stories of Super-Science, December 1930 Evolutions: Essential Tales of the Halo Universe

Evolutions: Essential Tales of the Halo Universe Good Stories Reprinted from the Ladies' Home Journal of Philadelphia

Good Stories Reprinted from the Ladies' Home Journal of Philadelphia Dragons!

Dragons! Murder Takes a Holiday

Murder Takes a Holiday Legacies of Betrayal

Legacies of Betrayal STAR WARS: TALES FROM THE CLONE WARS

STAR WARS: TALES FROM THE CLONE WARS Strange New Worlds 2016

Strange New Worlds 2016 Lippincott's Magazine, August, 1885

Lippincott's Magazine, August, 1885 Golden Age of Science Fiction Vol X

Golden Age of Science Fiction Vol X Hot Stuff

Hot Stuff Santa Wore Spurs

Santa Wore Spurs Paranormal Erotica

Paranormal Erotica Tangled Hearts: A Menage Collection

Tangled Hearts: A Menage Collection Sweet Tea and Jesus Shoes

Sweet Tea and Jesus Shoes The Journey Prize Stories 25

The Journey Prize Stories 25 Wild Western Tales 2: 101 Classic Western Stories Vol. 2 (Civitas Library Classics)

Wild Western Tales 2: 101 Classic Western Stories Vol. 2 (Civitas Library Classics) (5/15) The Golden Age of Science Fiction Volume V: An Anthology of 50 Short Stories

(5/15) The Golden Age of Science Fiction Volume V: An Anthology of 50 Short Stories (4/15) The Golden Age of Science Fiction Volume IV: An Anthology of 50 Short Stories

(4/15) The Golden Age of Science Fiction Volume IV: An Anthology of 50 Short Stories Ten Journeys

Ten Journeys The Boss

The Boss The Penguin Book of French Poetry

The Penguin Book of French Poetry Golden Age of Science Fiction Vol VIII

Golden Age of Science Fiction Vol VIII His Cinderella Housekeeper 3-in-1

His Cinderella Housekeeper 3-in-1 The Magazine of Fantasy & Science Fiction - July/August 2016

The Magazine of Fantasy & Science Fiction - July/August 2016 PYRATE CTHULHU - Tales of the Cthulhu Mythos (vol.2)

PYRATE CTHULHU - Tales of the Cthulhu Mythos (vol.2) Tales from a Master's Notebook

Tales from a Master's Notebook April 1930

April 1930 New Erotica 6

New Erotica 6 Damocles

Damocles The Longest Night Vol. 1

The Longest Night Vol. 1 The Golden Age of Science Fiction Volume VI: An Anthology of 50 Short Stories

The Golden Age of Science Fiction Volume VI: An Anthology of 50 Short Stories (1/15) The Golden Age of Science Fiction: An Anthology of 50 Short Stories

(1/15) The Golden Age of Science Fiction: An Anthology of 50 Short Stories Eye of Terra

Eye of Terra ONCE UPON A REGENCY CHRISTMAS

ONCE UPON A REGENCY CHRISTMAS Nexus Confessions

Nexus Confessions Passionate Kisses

Passionate Kisses War Without End

War Without End Doctor Who: Time Lord Fairy Tales

Doctor Who: Time Lord Fairy Tales Gotrek and Felix: The Anthology

Gotrek and Felix: The Anthology WESTERN CHRISTMAS PROPOSALS

WESTERN CHRISTMAS PROPOSALS The Journey Prize Stories 27

The Journey Prize Stories 27 The Silent War

The Silent War Liaisons

Liaisons Ellora's Cavemen: Tales from the Temple IV

Ellora's Cavemen: Tales from the Temple IV Ellora's Cavemen: Tales from the Temple II

Ellora's Cavemen: Tales from the Temple II Some of the Best From Tor.com, 2013 Edition: A Tor.Com Original

Some of the Best From Tor.com, 2013 Edition: A Tor.Com Original Urban Occult

Urban Occult Fractures

Fractures The Stories: Five Years of Original Fiction on Tor.com

The Stories: Five Years of Original Fiction on Tor.com The Penguin Book of Modern British Short Stories

The Penguin Book of Modern British Short Stories Mortarch of Night

Mortarch of Night The Portable Nineteenth-Century African American Women Writers

The Portable Nineteenth-Century African American Women Writers The Golden Age of Science Fiction Volume VII: An Anthology of 50 Short Stories

The Golden Age of Science Fiction Volume VII: An Anthology of 50 Short Stories Holy Bible: King James Version, The

Holy Bible: King James Version, The Eight Rooms

Eight Rooms sanguineangels

sanguineangels DarkNightsWithaBillionaireBundle

DarkNightsWithaBillionaireBundle Casserole Diplomacy and Other Stories

Casserole Diplomacy and Other Stories How I Survived My Summer Vacation

How I Survived My Summer Vacation Alfred Hitchcock Presents: 16 Skeletons From My Closet

Alfred Hitchcock Presents: 16 Skeletons From My Closet Lords, Ladies, Butlers and Maids

Lords, Ladies, Butlers and Maids The B4 Leg

The B4 Leg Ellora's Cavemen: Tales from the Temple I

Ellora's Cavemen: Tales from the Temple I 2014 Campbellian Anthology

2014 Campbellian Anthology There Is Only War

There Is Only War Obsidian Alliances

Obsidian Alliances 12 Gifts for Christmas

12 Gifts for Christmas Scary Holiday Tales to Make You Scream

Scary Holiday Tales to Make You Scream 25 For 25

25 For 25 The Plagues of Orath

The Plagues of Orath And Then He Kissed Me

And Then He Kissed Me Star Trek - Gateways 7 - WHAT LAY BEYOND

Star Trek - Gateways 7 - WHAT LAY BEYOND Laugh Your Head Off Again and Again

Laugh Your Head Off Again and Again The Balfour Legacy

The Balfour Legacy Golden Age of Science Fiction Vol XI

Golden Age of Science Fiction Vol XI (3/15) The Golden Age of Science Fiction Volume III: An Anthology of 50 Short Stories

(3/15) The Golden Age of Science Fiction Volume III: An Anthology of 50 Short Stories Shas'o

Shas'o Astounding Science Fiction Stories: An Anthology of 350 Scifi Stories Volume 2 (Halcyon Classics)

Astounding Science Fiction Stories: An Anthology of 350 Scifi Stories Volume 2 (Halcyon Classics) Twists in Time

Twists in Time Meduson

Meduson The Magazine of Fantasy & Science Fiction - August 1980

The Magazine of Fantasy & Science Fiction - August 1980 The Journey Prize Stories 22

The Journey Prize Stories 22 The Book that Made Me

The Book that Made Me Angels of Death Anthology

Angels of Death Anthology Ask the Bones

Ask the Bones Emergence

Emergence Beware the Little White Rabbit

Beware the Little White Rabbit Xcite Delights Book 1

Xcite Delights Book 1 Where flap the tatters of the King

Where flap the tatters of the King The Journey Prize Stories 21

The Journey Prize Stories 21 Tales of the Slayer, Volume II

Tales of the Slayer, Volume II Glass Empires

Glass Empires Golden Age of Science Fiction Vol XII

Golden Age of Science Fiction Vol XII (2/15) The Golden Age of Science Fiction Volume II: An Anthology of 50 Short Stories

(2/15) The Golden Age of Science Fiction Volume II: An Anthology of 50 Short Stories Fairytale Collection

Fairytale Collection Angels!

Angels! Golden Age of Science Fiction Vol XIII

Golden Age of Science Fiction Vol XIII