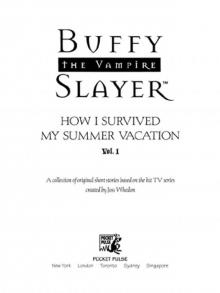

How I Survived My Summer Vacation Read online

Page 2

She opened her arms and swept her daughter into a hug —

And her daughter stiffened and paled, overwhelmed by the sudden smell of antiseptic cleaners that couldn’t quite mask the scent of less pleasant things. She stood at the foot of a hospital bed that had been decorated superficially — different sheets, a nonstandard bedspread — to look as if it were anything else. In that bed, head in the center of a pillow, was a withered old woman. It took a second.

Mom . . .

Her mother. Her lips were sunken over a jawline that clearly had no teeth; her eyes were closed. She was struggling for breath; failing to catch it.

Not a pretty sight, is it? But that’s mortality’s ugly little secret. You might be lucky enough to be spared, Slayer. I believe it’s unusual for someone in your vocation to survive their first quarter century.

I know I’ve done my best to give you a death you deserve. And isn’t any death better than this one?

She turned slowly, her eyes wide in that unblinking stare that was halfway between disbelief and fear.

In the light through the door, a shadow lay, long and thin against the ground. The familiar voice accompanied a familiar shadow. But nothing seemed to cast it, and when she turned back to the bed, she was alone with her mother’s death.

And the fear of the Master.

Rigor mortis would have left Buffy more flexible than the shock of her mother’s death. She had never thought of her mother as particularly young. But she couldn’t see how the woman in front of her could somehow disintegrate into whatever it was that had been left in that bed.

“Buffy?”

She had never really thought about her mother’s death before. Her mother was the single constant in a life that suddenly didn’t seem all that long. She wanted to shout, or to cry, or to fight something, but there was nothing at all she could do: age was age. It wasn’t a vampire, a demon, or a man-eating insect. It was a . . . fate.

God, she hated that word.

“Buffy, are you all right?”

No.

“I’m . . . I’m fine. I just remembered that I . . . I forgot to . . . to pack something I need. Dad’ll be here any minute.” She didn’t push her mother away because she’d been taught, over and over again, that Slayer strength against normal person could lead to permanent injury, but the desire to shove and escape was visceral. Desperate.

She escaped, fleeing up the familiar stairs, ducking into the familiar room, and closing the door behind her. Then she stopped. Leaned into it, palms against the pale surface of painted wood. Wondered if she had been — no, would be — one of those daughters who said, “I can’t visit my mom in the nursing home because I want to remember her as she was,” thereby forgetting everything that she ultimately had shared with her mother: company, time, even arguments.

The doorbell rang.

“Buffy!” Her mother’s voice, muffled by the door, was clear and strong. “Your father’s here!”

She came down the stairs quietly, a jacket that she hadn’t packed — and probably wouldn’t wear — slung over folded arms.

“Buffy!” Hank Summers opened his arms in that prelude to bearhug that was so familiar.

She stopped at the foot of the stairs. The distance between the last step and her father was about fifteen feet, and she made no move to lessen it. “Hi, Dad.”

She knew what was coming, and she did not want to see it. She wanted to see her dad like this, like a whole person, like someone young and vital and aware of her.

His smile went from open and natural to frozen and stiff in the amount of time it would have taken her to walk that stretch of space. He lowered his arms. Empty arms.

“Buffy.” Her mother’s voice dropped slightly at the end of the first syllable. “Is something wrong?”

“No. No, nothing’s wrong.”

The man and the woman whose only common bond now was the young woman at the foot of the stairs watched her a little too carefully. The man looked away.

“Dad . . . I’m fine, it’s just . . . I —”

He bent down and picked up her suitcases. “I’ll see you in the car.”

The car was about as comfortable as a car could be when occupied by two people and a large, awkward silence. After the first three attempts to point out interesting trees, a billboard, and the weather, father and daughter settled into an unspoken agreement: Buffy’s half of the car was the passenger side; her father’s was the driver’s. The parking break in the center was the great divide.

It was a two hour drive that might as well have lasted two weeks. And in between one of them, Hank Summers said to his daughter, his brows drawn in, his teeth slightly clenched, “Did Joyce — did your mother tell you anything recently?”

“How to pack enough underwear for a decade of clean living?”

He chuckled in a way that made his smile seem natural. “Did she tell you anything about me?”

“That she wanted us to get off on the right foot, which I guess we haven’t.” She closed her eyes, then opened them, and caught her father’s eyes in the mirror as if that were the only safe way to look at them. Which, given that he was driving, was probably true. “Look, Dad — I’m sorry I was so distant. I haven’t —”

“Because I told her about Wendy in strict confidence, and I asked her to let me break it to you in my own way. I guess she didn’t think my own way would be gentle enough.”

“— been myself lately. I really had to . . . Wendy?”

“Wendy.”

“We don’t even have Dave Thomas commercials in Sunnydale. Are you telling me something in your life besides a fast-food franchise is using that name?”

He was silent for a long time, driving quickly absorbing his attention the way paper towels in cheesy commercials absorb spills. “It looks like I owe your mother an apology.”

“And me an explanation?”

“And you an explanation. I’ve —” He chuckled again. Buffy had heard fingernails and blackboards that sounded more pleasant. “I’ve recently started seeing someone.”

“Seeing someone.”

“A woman I met at the office. A client of a friend.”

“A client. Of a friend.”

“Buffy —”

“When exactly is recently?”

“In the last couple of weeks. She’s a great person, Buffy. I think you’ll both get along really well.”

“Are we going to be seeing a lot of each other?”

The smile cracked. “We haven’t finalized any plans yet,” he said quietly, “but if things work out in the next month or two, Wendy and I will probably be moving in together.”

“Oh.” Buffy leaned forward and hit the automatic button on the armrest that dragged the window from the top of the frame to the bottom. The air that rushed past her face was smoggy and full of car exhaust — but it was loud. Familiar.

When L.A. had proved a little too hot for comfort — the distinct aftermath of burning down a school — the Summers’ marriage began the process of being consigned to paper, along with the house that Buffy had called home in the simple years before some lunatic with a death wish had found her on the steps of her old high school.

She wasn’t particularly fond of guilt, and she didn’t indulge in it often, but she wondered from time to time if her parents could have fixed what was wrong with their marriage if they hadn’t had to deal with what was wrong with their daughter’s life.

How much of her parents’ marital problems had been Slayer problems? How often had they argued about the hours she kept when she’d had a later-than-midnight rendezvous she couldn’t avoid making if she didn’t want the city to wind up as a mobile blood bank for vampires?

And when exactly had her father been planning on telling her about the new girlfriend?

“Buffy?” Hank Summers, bent by the weight of a summer’s worth of his daughter’s clothing, stopped at the foot of his property line. “Do you like it?”

“Wow, Dad. I knew you never liked yard wo

rk, but this is a big change.” There it was again, that “change” word.

No house greeted her; the grounds that stretched out from one end of the block to the other fronted a stretch of apartments. One of which was her father’s.

“I know it’s not . . . not home.”

She nodded. It wasn’t home. She hadn’t thought it would bother her. And it hadn’t — until she looked at this building, at this building that she might be happy to live in one day, on her own, and realized that she could not go home. Not to the home she had had before she had been discovered as the Slayer. Not to the time when her biggest tragedy was who the best friend of the day was.

“I kept your room. I mean, I have a room here that’s just for you.”

She smiled, and if the smile was a bit stiff, it was genuine. She didn’t even ask him who decorated it. But as she walked toward the building’s entrance, other thoughts intruded. The girl on vacation with her father moved over and the Slayer stepped in. She knew just how far she could jump, how thick a window she could expect to break with her fist, foot or elbow, and how much of a midair recovery she could make if she didn’t have a chance to slow her momentum when she was going out the window. These were the things she looked for in a place these days. She followed her father, absently, looking at glass, at light — at how much light — streaming through the uncurtained windows.

“These are yours,” he said quietly.

“Hmmm? Oh. Keys.” She took them carefully, trying not to touch him. Trying not to show how hard she was trying.

“I thought I’d let you try them out.”

“Here?”

“Here. This is home in L.A. from now on.”

“Dad?”

He stopped.

“I can carry one of those.” Buffy held out a slender hand.

“I’m fine.” Which was true, if one counted struggling with suitcases that weighed maybe a little too much to be fine.

“But I —”

“You haven’t changed much, have you?” She froze.

“You haven’t wanted my help since you turned thirteen.”

“Thirteen?”

“Give or take a few months. You got so independent so quickly. It seems like I took a business trip one month and came back to a whole new girl.”

“I think I was older than thirteen.” She let him carry the suitcase. She even made it down the hall to the door he seemed to be aiming at before she finally turned to see him struggling slightly. “When were you planning on telling me about Wendy?” She put her hand on the door; it was solid; thick. The knob was standard brass.

On the other hand, maybe it was cheap aluminium with a brass enamel. Real brass doorknobs didn’t usually bend when someone gripped them a little too hard.

“Does it matter? I didn’t mean to hide it. I’m not ashamed of Wendy. I just thought you’d rather hear about it in person than over a phone line.”

“But you could tell Mom.”

“Buffy —”

“You couldn’t live with her, but you could tell her.”

There wasn’t much he could say.

The room was large.

The window was half the size of the west wall with curtains that matched the bed. The bed itself . . . was a canopy bed. She had loved canopy beds as a child, and although it had been years since anyone had called her a child, some echo of excitement remained.

“I know I should have let you choose your own things,” her father said, watching her expression. “I’m sorry. But I —”

“No, Dad, it’s perfect. It’s like my old room. I mean, my old room. It’s . . . it looks like it’s even the same bed.”

“It is the same bed.”

“But you said —”

“I said I was going to get rid of it because you said you never wanted to see it again. But I remembered going to buy it for you. I remembered how happy you were when it arrived. I wanted to hold on to that. And I just . . . I put it into storage.”

“You kept it?”

“I kept it.” He exhaled, a big man who seemed inches shorter than the last time she’d really looked at him. “Buffy . . . I don’t know what we did wrong as parents. You should have been that happy for all of your life. That’s all we wanted for you. But — God, you’re so much better with words than I am.”

He’d put the suitcases down.

And she wasn’t thinking clearly.

When he opened his arms, she walked right into them. It was like coming home.

If home was a morgue.

The carpet was bright. Her father had been lying against it, thrashing, ten years older than he was at this moment, but heavier. No obvious signs of violence, there. Heart attack, maybe. And against the body in motion, a shadow in stillness.

You haven’t really escaped me, you know. You were meant to die, and you can’t cheat death without consequences.

“I didn’t cheat death. I have friends.”

True. And look at how they end up. In fact, you will look at how they end their pathetic lives for the rest of your life.

“You’re dead.”

I am. But that didn’t stop you, and you’re just a little girl with delusions of grandeur.

“Well, at least I’m not ugly.”

True. But you will be. Just think about your mother. Or your father, for that matter. There’s only one way to stay young and beautiful forever.

She would have told him to go to hell, but it occurred to her that she’d already sent him there once.

She had watched her father die in silence because she hadn’t been about to share her pain in front of witnesses. Especially this one.

“Buffy?”

“I’m . . . I’m fine.”

“Buffy, if you’re angry at me, could you just come out and say it?”

“If I was angry at you, I’d tell you. I just . . . have car sickness. I’m still car sick.”

“Car sick?” He hadn’t mustered much in the way of belief.

“It’s a new thing. I get car sick a lot. Put me in a car for longer than five minutes, and — you don’t want to hear the messy details. I just need a half an hour to lie down.”

“Fine.” He walked toward the door.

“Dad?”

Stopped.

“I . . . I’m really glad that you kept the bed.”

“Buffy, the Master is dead.”

Her hands were shaking. The bed was shaking. “Giles — every time I touch somebody, I see them die.” She gripped the phone a little harder.

“You died yourself, Buffy. It’s just possible that you may have . . . issues . . . that need to be dealt with.”

“It’s not a matter of issues —”

“You’ve come face to face with mortality in a way that very few people your age ever have to. It’s not pleasant. It’s not gradual. You haven’t had a chance to grow ‘into’ it the way the rest of us have. But there’s nothing about the deaths that you’ve witnessed that suggest absolute truth.”

“Angel’s death.”

The voice on the other end of the phone was quiet for a while. “Are you so certain? You know that Darla sired him. You know that she was in love with him, that at some time he must have returned that love, in a demonic fashion. You know how old Angel is . . . you could easily have filled in those details.”

“With my grades in history this year?”

“Good point. But still . . . Buffy, I don’t mean to trivialize your experiences, and I am worried, but not about the supernatural in this case.”

“And the Master?”

“If you hadn’t seen or heard the Master, I’d consider this more threatening. I will do research — I am doing it — but the Master is dead, Buffy. Put your mind at rest. He’s gone.”

“Buffy,” Her father’s voice came out of the wall — or rather, the intercom speaker imbedded in it. Buffy jumped and walked over to the wall to look at the buttons. The panel was flat and devoid of any useful instructions, like “press here to answer.”

/>

“There’s a message on the answering machine for you.”

She pressed a button. “And the answering machine is where?” He didn’t answer. She pressed the next button. Then the next. That one worked.

“It’s an answering service. The code is beside the phone. You have your own voicemail box, if you want to use it.”

“Thanks, Dad. I didn’t expect to get much in the way of calls here.”

“It’s one of your old high school friends,” he said, sounding slightly surprised that she still had any. Which was a lot less surprised than Buffy was.

“It’s been months,” Amber Theirsen said. “I mean, months and months. You wouldn’t believe what’s happened since you’ve been gone. Well, I mean, after the renovations to the school. Anyway, what was I saying? Oh, right. Claudia? She’s going out with Jeff Thompson now. He dumped Laurie and she’s on the warpath. She’s done this thing with her hair that has to be seen to be believed. You’re gonna be with your dad for the summer, right? I stay with my dad for the summer, but at least both my parents still live in L.A. I mean, isn’t Sunnydale a one-street town?”

“Two. Well, one and a half.”

“So it’ll be a relief to be back where things are happening, right? I thought we could get together and maybe go shopping or something. My dad’s — I don’t mind staying here, but it’s so boring. You can come out, right?”

“I’d really like that. It’s been way too long.”

“Well, great! Because it has been so dead here, you know what I mean?”

“I think I have a pretty good idea of what dead means.”

“So come and save me from boredom. When did you want to do the see-me-in-person thing?”

“Well, I have —”

“Tonight is good.”

“I’m not sure tonight is great for me but —”

“Good. Got a pencil? I don’t think you’ve been to my dad’s place before. Let me give you the address.”

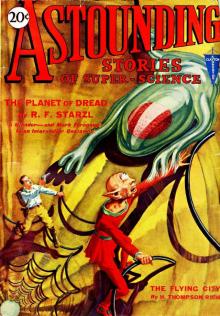

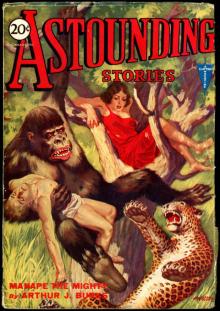

Astounding Stories, March, 1931

Astounding Stories, March, 1931 Astounding Stories, February, 1931

Astounding Stories, February, 1931 Futuria Fantasia, Spring 1940

Futuria Fantasia, Spring 1940 The King's Daughter and Other Stories for Girls

The King's Daughter and Other Stories for Girls Uncanny Tales

Uncanny Tales Masters of Noir: Volume Two

Masters of Noir: Volume Two Witty Pieces by Witty People

Witty Pieces by Witty People Sylvaneth

Sylvaneth Space Wolves

Space Wolves Hammerhal & Other Stories

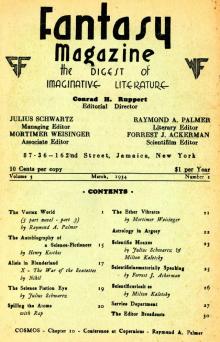

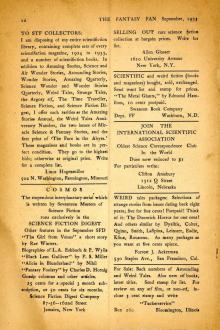

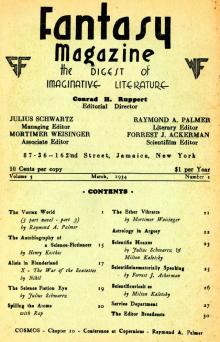

Hammerhal & Other Stories The Fantasy Fan, March, 1934

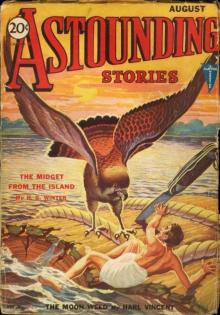

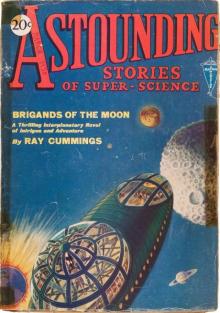

The Fantasy Fan, March, 1934 Astounding Stories of Super-Science, August 1930

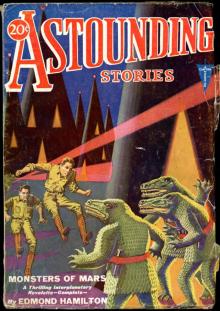

Astounding Stories of Super-Science, August 1930 Astounding Stories, August, 1931

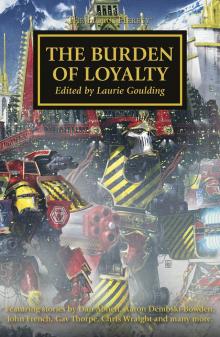

Astounding Stories, August, 1931 The Burden of Loyalty

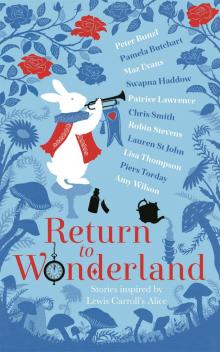

The Burden of Loyalty Return to Wonderland

Return to Wonderland Anthology - A Thousand Doors

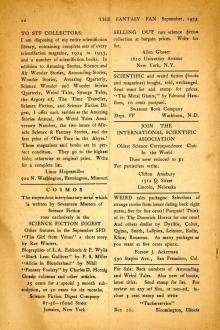

Anthology - A Thousand Doors The Fantasy Fan, October 1933

The Fantasy Fan, October 1933 Astounding Stories, June, 1931

Astounding Stories, June, 1931 Southern Stories

Southern Stories Astounding Stories of Super-Science, May, 1930

Astounding Stories of Super-Science, May, 1930 The Fantasy Fan December 1933

The Fantasy Fan December 1933 Adventures in Many Lands

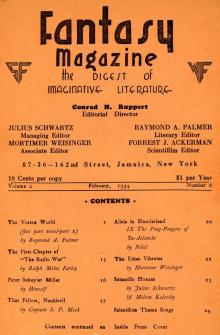

Adventures in Many Lands The Fantasy Fan February 1934

The Fantasy Fan February 1934 The Fantasy Fan November 1933

The Fantasy Fan November 1933 Astounding Stories, April, 1931

Astounding Stories, April, 1931 Fame and Fortune Weekly, No. 801, February 4, 1921

Fame and Fortune Weekly, No. 801, February 4, 1921 Astounding Stories of Super-Science, November, 1930

Astounding Stories of Super-Science, November, 1930 Astounding Stories of Super-Science January 1931

Astounding Stories of Super-Science January 1931 A Monk of Fife

A Monk of Fife Astounding Stories of Super-Science September 1930

Astounding Stories of Super-Science September 1930 Astounding Stories of Super-Science July 1930

Astounding Stories of Super-Science July 1930 Astounding Stories of Super-Science, June, 1930

Astounding Stories of Super-Science, June, 1930 Astounding Stories of Super-Science, October, 1930

Astounding Stories of Super-Science, October, 1930 Astounding Stories of Super-Science, March 1930

Astounding Stories of Super-Science, March 1930 The Fantasy Fan January 1934

The Fantasy Fan January 1934 The Fantasy Fan September 1933

The Fantasy Fan September 1933 Astounding Stories of Super-Science February 1930

Astounding Stories of Super-Science February 1930 Astounding Stories, May, 1931

Astounding Stories, May, 1931 Strange Stories of Colonial Days

Strange Stories of Colonial Days Golden Age of Science Fiction Vol IX

Golden Age of Science Fiction Vol IX Astounding Stories of Super-Science, December 1930

Astounding Stories of Super-Science, December 1930 Evolutions: Essential Tales of the Halo Universe

Evolutions: Essential Tales of the Halo Universe Good Stories Reprinted from the Ladies' Home Journal of Philadelphia

Good Stories Reprinted from the Ladies' Home Journal of Philadelphia Dragons!

Dragons! Murder Takes a Holiday

Murder Takes a Holiday Legacies of Betrayal

Legacies of Betrayal STAR WARS: TALES FROM THE CLONE WARS

STAR WARS: TALES FROM THE CLONE WARS Strange New Worlds 2016

Strange New Worlds 2016 Lippincott's Magazine, August, 1885

Lippincott's Magazine, August, 1885 Golden Age of Science Fiction Vol X

Golden Age of Science Fiction Vol X Hot Stuff

Hot Stuff Santa Wore Spurs

Santa Wore Spurs Paranormal Erotica

Paranormal Erotica Tangled Hearts: A Menage Collection

Tangled Hearts: A Menage Collection Sweet Tea and Jesus Shoes

Sweet Tea and Jesus Shoes The Journey Prize Stories 25

The Journey Prize Stories 25 Wild Western Tales 2: 101 Classic Western Stories Vol. 2 (Civitas Library Classics)

Wild Western Tales 2: 101 Classic Western Stories Vol. 2 (Civitas Library Classics) (5/15) The Golden Age of Science Fiction Volume V: An Anthology of 50 Short Stories

(5/15) The Golden Age of Science Fiction Volume V: An Anthology of 50 Short Stories (4/15) The Golden Age of Science Fiction Volume IV: An Anthology of 50 Short Stories

(4/15) The Golden Age of Science Fiction Volume IV: An Anthology of 50 Short Stories Ten Journeys

Ten Journeys The Boss

The Boss The Penguin Book of French Poetry

The Penguin Book of French Poetry Golden Age of Science Fiction Vol VIII

Golden Age of Science Fiction Vol VIII His Cinderella Housekeeper 3-in-1

His Cinderella Housekeeper 3-in-1 The Magazine of Fantasy & Science Fiction - July/August 2016

The Magazine of Fantasy & Science Fiction - July/August 2016 PYRATE CTHULHU - Tales of the Cthulhu Mythos (vol.2)

PYRATE CTHULHU - Tales of the Cthulhu Mythos (vol.2) Tales from a Master's Notebook

Tales from a Master's Notebook April 1930

April 1930 New Erotica 6

New Erotica 6 Damocles

Damocles The Longest Night Vol. 1

The Longest Night Vol. 1 The Golden Age of Science Fiction Volume VI: An Anthology of 50 Short Stories

The Golden Age of Science Fiction Volume VI: An Anthology of 50 Short Stories (1/15) The Golden Age of Science Fiction: An Anthology of 50 Short Stories

(1/15) The Golden Age of Science Fiction: An Anthology of 50 Short Stories Eye of Terra

Eye of Terra ONCE UPON A REGENCY CHRISTMAS

ONCE UPON A REGENCY CHRISTMAS Nexus Confessions

Nexus Confessions Passionate Kisses

Passionate Kisses War Without End

War Without End Doctor Who: Time Lord Fairy Tales

Doctor Who: Time Lord Fairy Tales Gotrek and Felix: The Anthology

Gotrek and Felix: The Anthology WESTERN CHRISTMAS PROPOSALS

WESTERN CHRISTMAS PROPOSALS The Journey Prize Stories 27

The Journey Prize Stories 27 The Silent War

The Silent War Liaisons

Liaisons Ellora's Cavemen: Tales from the Temple IV

Ellora's Cavemen: Tales from the Temple IV Ellora's Cavemen: Tales from the Temple II

Ellora's Cavemen: Tales from the Temple II Some of the Best From Tor.com, 2013 Edition: A Tor.Com Original

Some of the Best From Tor.com, 2013 Edition: A Tor.Com Original Urban Occult

Urban Occult Fractures

Fractures The Stories: Five Years of Original Fiction on Tor.com

The Stories: Five Years of Original Fiction on Tor.com The Penguin Book of Modern British Short Stories

The Penguin Book of Modern British Short Stories Mortarch of Night

Mortarch of Night The Portable Nineteenth-Century African American Women Writers

The Portable Nineteenth-Century African American Women Writers The Golden Age of Science Fiction Volume VII: An Anthology of 50 Short Stories

The Golden Age of Science Fiction Volume VII: An Anthology of 50 Short Stories Holy Bible: King James Version, The

Holy Bible: King James Version, The Eight Rooms

Eight Rooms sanguineangels

sanguineangels DarkNightsWithaBillionaireBundle

DarkNightsWithaBillionaireBundle Casserole Diplomacy and Other Stories

Casserole Diplomacy and Other Stories How I Survived My Summer Vacation

How I Survived My Summer Vacation Alfred Hitchcock Presents: 16 Skeletons From My Closet

Alfred Hitchcock Presents: 16 Skeletons From My Closet Lords, Ladies, Butlers and Maids

Lords, Ladies, Butlers and Maids The B4 Leg

The B4 Leg Ellora's Cavemen: Tales from the Temple I

Ellora's Cavemen: Tales from the Temple I 2014 Campbellian Anthology

2014 Campbellian Anthology There Is Only War

There Is Only War Obsidian Alliances

Obsidian Alliances 12 Gifts for Christmas

12 Gifts for Christmas Scary Holiday Tales to Make You Scream

Scary Holiday Tales to Make You Scream 25 For 25

25 For 25 The Plagues of Orath

The Plagues of Orath And Then He Kissed Me

And Then He Kissed Me Star Trek - Gateways 7 - WHAT LAY BEYOND

Star Trek - Gateways 7 - WHAT LAY BEYOND Laugh Your Head Off Again and Again

Laugh Your Head Off Again and Again The Balfour Legacy

The Balfour Legacy Golden Age of Science Fiction Vol XI

Golden Age of Science Fiction Vol XI (3/15) The Golden Age of Science Fiction Volume III: An Anthology of 50 Short Stories

(3/15) The Golden Age of Science Fiction Volume III: An Anthology of 50 Short Stories Shas'o

Shas'o Astounding Science Fiction Stories: An Anthology of 350 Scifi Stories Volume 2 (Halcyon Classics)

Astounding Science Fiction Stories: An Anthology of 350 Scifi Stories Volume 2 (Halcyon Classics) Twists in Time

Twists in Time Meduson

Meduson The Magazine of Fantasy & Science Fiction - August 1980

The Magazine of Fantasy & Science Fiction - August 1980 The Journey Prize Stories 22

The Journey Prize Stories 22 The Book that Made Me

The Book that Made Me Angels of Death Anthology

Angels of Death Anthology Ask the Bones

Ask the Bones Emergence

Emergence Beware the Little White Rabbit

Beware the Little White Rabbit Xcite Delights Book 1

Xcite Delights Book 1 Where flap the tatters of the King

Where flap the tatters of the King The Journey Prize Stories 21

The Journey Prize Stories 21 Tales of the Slayer, Volume II

Tales of the Slayer, Volume II Glass Empires

Glass Empires Golden Age of Science Fiction Vol XII

Golden Age of Science Fiction Vol XII (2/15) The Golden Age of Science Fiction Volume II: An Anthology of 50 Short Stories

(2/15) The Golden Age of Science Fiction Volume II: An Anthology of 50 Short Stories Fairytale Collection

Fairytale Collection Angels!

Angels! Golden Age of Science Fiction Vol XIII

Golden Age of Science Fiction Vol XIII