Golden Age of Science Fiction Vol VIII Read online

Page 2

"We could rouse them a few at a time, let them vote, and put them back to sleep," suggested Teresa Zeleny.

"It would take weeks," said Coffin. "You, of all people, should know metabolism isn't lightly stopped, or easily restored."

"If you could see my face," she said, again with a chuckle, "I would grimace amen. I'm so sick of tending inert human flesh that ... well, I'm glad they're only women and girls, because if I also had to massage and inject men I'd take a vow of chastity!"

Coffin blushed, cursed himself for blushing, and hoped she couldn't see it over the telecircuit. He noticed Kivi grin.

* * * * *

Kivi provided the merciful interruption. "Your few-at-a-time proposal is pointless anyhow," he said. "In the course of those weeks, we would pass the critical date."

"What's that?" asked a young girl's voice.

"You don't know?" said Coffin, surprised.

"Let it pass for now," broke in Teresa. Once again, as several times before, Coffin admired her decisiveness. She cut through nonsense with a man's speed and a woman's practicality. "Take our word for it, June, if we don't turn about within two months, we'll do better to go on to Rustum. So, voting is out. We could wake a few sleepers, but those already conscious are really as adequate a statistical sample."

Coffin nodded. She spoke for five women on her ship, who stood a year-watch caring for two hundred ninety-five asleep. The one hundred twenty who would not be restimulated for such duty during the voyage, were children. The proportion on the other nine colonist-laden vessels was similar; the crew totaled one thousand six hundred twenty, with forty-five up and about at all times. Whether the die was cast by less than two per cent, or by four or five per cent, was hardly significant.

"Let's recollect exactly what the message was," said Coffin. "The educational decree which directly threatened your Constitutionalist way of life has been withdrawn. You're no worse off now than formerly--and no better, though there's a hint of further concessions in the future. You're invited home again. That's all. We have not picked up any other transmissions. It seems very little data on which to base so large a decision."

"It's an even bigger one, to continue," said de Smet. He leaned forward, a bulky man, until he filled his little screen. Hardness rang in his tones. "We were able people, economically rather well off. I daresay Earth already misses our services, especially in technological fields. Your own report makes Rustum out a grim place; many of us would die there. Why should we not turn home?"

"Home," whispered someone.

The word filled a sudden quietness, like water filling a cup, until quietness brimmed over with it. Coffin sat listening to the voice of his ship, generators, ventilators, regulators, and he began to hear a beat frequency which was Home, home, home.

Only his home was gone. His father's church was torn down for an Oriental temple, and the woods where October had burned were cleared for another tentacle of city, and the bay was enclosed to make a plankton farm. For him, only a spaceship remained, and the somehow cold hope of heaven.

A very young man said, almost to himself: "I left a girl back there."

"I had a little sub," said another. "I used to poke around the Great Barrier Reef, skindiving out the air lock or loafing on the surface. You wouldn't believe how blue the waves could be. They tell me on Rustum you can't come down off the mountain tops."

"But we'd have the whole planet to ourselves," said Teresa Zeleny.

One with a gentle scholar's face answered: "That may be precisely the trouble, my dear. Three thousand of us, counting children, totally isolated from the human mainstream. Can we hope to build a civilization? Or even maintain one?"

"Your problem, pop," said the officer beside him dryly, "is that there are no medieval manuscripts on Rustum."

"I admit it," said the scholar. "I thought it more important my children grow up able to use their minds. But if it turns out they can do so on Earth--How much chance will the first generations on Rustum have to sit down and really think, anyway?"

"Would there even be a next generation on Rustum?"

"One and a quarter gravities--I can feel it now."

"Synthetics, year after year of synthetics and hydroponics, till we can establish an ecology. I had steak on Earth, once in a while."

"My mother couldn't come. Too frail. But she's paid for a hundred years of deepsleep, all she could afford ... just in case I do return."

"I designed skyhouses. They won't build anything on Rustum much better than sod huts, in my lifetime."

"Do you remember moonlight on the Grand Canyon?"

"Do you remember Beethoven's Ninth in the Federal Concert Hall?"

"Do you remember that funny little Midlevel bar, where we all drank beer and sang Lieder?"

"Do you remember?"

"Do you remember?"

* * * * *

Teresa Zeleny shouted across their voices: "In Anker's name! What are you thinking about? If you care so little, you should never have embarked in the first place!"

It brought back the silence, not all at once but piece by piece, until Coffin could pound the table and call for order. He looked straight at her hidden eyes and said: "Thank you, Miss Zeleny. I was expecting tears to be uncorked any moment."

One of the girls snuffled behind her mask.

Charles Lochaber, speaking for the Courier colonists, nodded. "Aye, 'tis a blow to our purpose. I am not so sairtain I myself would vote to continue, did I feel the message was to be trusted."

"What?" De Smet's square head jerked up from between his shoulders.

Lochaber grinned without much humor. "The government has been getting more arbitrary each year," he said. "They were ready enough to let us go, aye. But they may regret it now--not because we could ever be any active threat, but because we will be a subversive example, up there in Earth's sky. Or just because we will be. Mind ye, I know not for sairtain; but 'tis possible they decided we are safer dead, and this is to trick us back. 'Twould be characteristic dictatorship behavior."

"Of all the fantastic--" gasped an indignant female voice.

Teresa broke in: "Not as wild as you might think, dear. I have read a little history, and I don't mean that censored pap which passes for it nowadays. But there's another possibility, which I think is just as alarming. That message may be perfectly honest and sincere. But will it still be true when we get back? Remember how long that will take! And even if we could return overnight, to an Earth which welcomed us home, what guarantee would there be that our children, or our grandchildren, won't suffer the same troubles as us, without the same chance to break free?"

"Ye vote, then, to carry on?" asked Lochaber.

Pride answered: "Of course."

"Good lass. I, too."

Kivi raised his hand. Coffin recognized him, and the spaceman said: "I am not sure the crew ought not to have a voice in this also."

"What?" De Smet grew red. He gobbled for a moment before he could get out: "Do you seriously think you could elect us to settle on that annex of hell--and then come home to Earth yourselves?"

"As a matter of fact," said Kivi, smiling, "I suspect the crew would prefer to return at once. I know I would. Seven years may make a crucial difference."

"If a colony is planted, though," said Coffin, "it might provide the very inspiration which space travel needs to survive."

"Hm-m-m. Perhaps. I shall have to think about that."

"I hope you realize," said the very young man with ornate sarcasm, "that every second we sit here arguing takes us one hundred fifty thousand kilometers farther from home."

"Dinna fash yourself," said Lochaber. "Whatever we do, that girl of yours will be an auld carline before you reach Earth."

De Smet was still choking at Kivi: "You lousy little ferryman, if you think you can make pawns of us--"

And Kivi stretched his lips in anger and growled, "If you do not watch your language, you clodhugger, I will come over there and stuff you down your own throat."

Teresa echoed him: "Please ... for all our lives' sake ... don't you know where we are? You've got a few centimeters of wall between you and zero! Please, whatever we do, we can't fight or we'll never see any planet again!"

But she did not say it weeping, or as a beggary. It was almost a mother's voice--strange, in an unmarried woman--and it quieted the male snarling more than Coffin's shouts.

The fleet captain said finally: "That will do. You're all too worked up to think. Debate is adjourned sixteen hours. Discuss the problem with your shipmates, get some sleep, and report the consensus at the next meeting."

"Sixteen hours?" yelped someone. "Do you know how much return time that adds?"

"You heard me," said Coffin. "Anybody who wants to argue may do so from the brig. Dismissed!"

He snapped off the switch.

Kivi, temper eased, gave him a slow confidential grin. "That heavy-father act works nearly every time, no?"

Coffin pushed from the table. "I'm going out," he said. His voice sounded harsh to him, a stranger's. "Carry on."

He had never felt so alone before, not even the night his father died. O God, who spake unto Moses in the wilderness, reveal now thy will. But God was silent, and Coffin turned blindly to the only other help he could think of.

* * * * *

Space armored, he paused a moment in the air lock before continuing. He had been an astronaut for twenty-five years--for a century if you added time in the vats--but he could still not look upon naked creation without fear.

An infinite blackness flashed: stars beyond stars, to the bright ghost-road of the Milky Way and on out to other galaxies and flocks of galaxies, until the light which a telescope might now register had been born before the Earth. Looking from his air-lock cave, past the radio web and the other ships, Coffin felt himself drown in enormousness, coldness, and total silence--though he knew that this vacuum burned and roared with man-destroying energies, roiled like currents of gas and dust more massive than planets and travailed with the birth of new suns--and he said to himself the most dreadful of names, I am that I am, and sweat formed chilly little globules under his arms.

This much a man could see within the Solar System. Traveling at half light-speed stretched the human mind still further, till often it ripped across and another lunatic was shoved into deepsleep. For aberration redrew the sky, crowding stars toward the bows, so that the ships plunged toward a cloud of Doppler hell-blue. The constellations lay thinly abeam, you looked out upon the dark. Aft, Sol was still the brightest object in heaven, but it had gained a sullen red tinge, as if already grown old, as if the prodigal would return from far places to find his home buried under ice.

What is man that thou art mindful of him? The line gave its accustomed comfort; for, after all, the Sun-maker had also wrought this flesh, atom by atom, and at the very least would think it worthy of hell. Coffin had never understood how his atheist colleagues endured free space.

Well--

He took aim at the next hull and fired his little spring-powered crossbow. A light line unreeled behind the magnetic bolt. He tested its security with habitual care, pulled himself along until he reached the companion ship, yanked the bolt loose and fired again, and so on from hull to slowly orbiting hull, until he reached the Pioneer.

Its awkward ugly shape was like a protective wall against the stars. Coffin drew himself past the ion tubes, now cold. Their skeletal structure seemed impossibly frail to have hurled forth peeled atoms at one half c. Mass tanks bulked around the vessel; allowing for deceleration, plus a small margin, the mass ratio was about nine to one. Months would be required at Rustum to refine enough reaction material for the home voyage. Meanwhile such of the crew as were not thus engaged would help the colony get established--

If it ever did!

Coffin reached the forward air lock and pressed the "doorbell." The outer valve opened for him, and he cycled through. First Officer Karamchand met him and helped him doff armor. The other man on duty found an excuse to approach and listen; for monotony was as corrosive out here as distance and strangeness.

"Ah, sir. What brings you over?"

Coffin braced himself. Embarrassment roughened his tone: "I want to see Miss Zeleny."

"Of course--But why come yourself? I mean, the telecircuit--"

"In person!" barked Coffin.

"What?" escaped the crewman. He propelled himself backward in terror of a wigging. Coffin ignored it.

"Emergency," he snapped. "Please intercom her and arrange for a private discussion."

"Why ... why ... yes, sir. At once. Will you wait here ... I mean ... yes, sir!" Karamchand shot down the corridor.

Coffin felt a sour smile on his own lips. He could understand if they got confused. His own law about the women had been like steel, and now he violated it himself.

The trouble was, he thought, no one knew if it was even required. Until now there had been few enough women crossing space, and then only within the Solar System, on segregated ships. There was no background of interstellar experience. It seemed reasonable, though, that a man on his year-watch should not be asked to tend deepsleeping female colonists. (Or vice versa!) The idea revolted Coffin personally; but for once the psychotechs had agreed with him. And, of course, waking men and women, freely intermingling, were potentially even more explosive. Haremlike seclusion appeared the only answer; and husband and wife were not to be awake at the same time.

Bad enough to see women veiled when there was a telecircuit conference. (Or did the masks make matters still worse, by challenging the imagination? Who knew?) Best seal off the living quarters and coldvat sections of the craft which bore them. Crewmen standing watches on those particular ships had better return to their own vessels to sleep and eat.

Coffin braced his muscles. The rules wouldn't apply if a large meteor struck, he reminded himself. What has come up is more dangerous than that. So never mind what anyone thinks.

Karamchand returned to salute him and say breathlessly: "Miss Zeleny will see you, captain. This way, if you please."

"Thanks." Coffin followed to the main bulkhead. The women had its doorkey. Now the door stood ajar. Coffin pushed himself through so hard that he overshot and caromed off the farther wall.

Teresa laughed. She closed the door and locked it. "Just to make them feel safe out there," she said. "Poor well-meaning men! Welcome, captain."

* * * * *

He turned about, almost dreading the instant. Her tall form was decent in baggy coveralls, but she had dropped the mask. She was not pretty, he supposed: broad-faced, square-jawed, verging on spinsterhood. But he had liked her way of smiling.

"I--" He found no words.

"Follow me." She led him down a short passage, hand-over-hand along the null-gee rungs. "I've warned the other girls to stay away. You needn't fear being shocked." At the end of the hall was a little partitioned-off room. Few enough personal goods could be taken along, but she had made this place hers, a painting, a battered Shakespeare, the works of Anker, a microplayer. Her tapes ran to Bach, late Beethoven and Strauss, music which could be studied endlessly. She took hold of a stanchion and nodded, all at once grown serious.

"What do you want to ask me, captain?"

Coffin secured himself by the crook of an arm and stared at his hands. The fingers strained against each other. "I wish I could give you a clear reply," he said, very low and with difficulty. "You see, I've never met anything like this before. If it involved only men, I guess I could handle the problem. But there are women along, and children."

"And you want a female viewpoint. You're wiser than I had realized. But why me?"

He forced himself to meet her eyes. "You appear the most sensible of the women awake."

"Really!" She laughed. "I appreciate the compliment, but must you deliver it in that parade-ground voice, and glare at me to boot? Relax, captain." She cocked her head, studying him. Then: "Several of the girls don't get this

business of the critical point. I tried to explain, but I was only an R.N. at home, and I'm afraid I muddled it rather. Could you put it in words of one and a half syllables?"

"Do you mean the equal-time point?"

"The Point of No Return, some of them call it."

"Nonsense! It's only--Well, look at it this way. We accelerated from Sol at one gravity. We dare not apply more acceleration, even though we could, because so many articles aboard have been lightly built to save mass--the coldvats, for example. They'd collapse under their own weight, and the persons within would die, if we went as much as one-point-five gee. Very well. It took us about one hundred eighty days to reach maximum velocity. In the course of that period, we covered not quite one-and-a-half light-months. We will now go free for almost forty years. At the end of that time, we'll decelerate at one gee for some one hundred eighty days, covering an additional light-month and a half, and enter the e Eridani System with low relative speed. Our star-to-star orbit was plotted with care, but of course the errors add up to many Astronomical Units; furthermore, we have to maneuver, put our ships in orbit about Rustum, send ferry craft back and forth. So we carry a reaction-mass reserve which allows us a total velocity change of about one thousand kilometers per second after journey's end.

"Now imagine we had changed our minds immediately after reaching full speed. We'd still have to decelerate in order to return. So we'd be almost a quarter light-year from Sol, a year after departure, before achieving relative rest. Then, to come back three light-months at one thousand K.P.S. takes roughly seventy-two years. But the whole round trip as originally scheduled, with a one-year layover at Rustum, runs just about eighty-three years!

"Obviously there's some point in time beyond which we can actually get home quicker by staying with the original plan. This date lies after eight months of free fall, or not quite fourteen months from departure. We're only a couple of months from the critical moment right now; if we start back at once, we'll still have been gone from Earth for about seventy-six years. Each day we wait adds months to the return trip. No wonder there's impatience!"

"And the relativity clock paradox makes it worse," Teresa said.

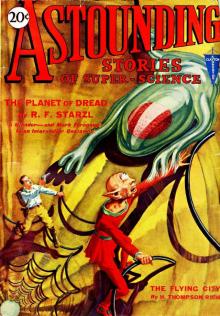

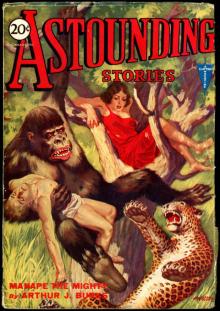

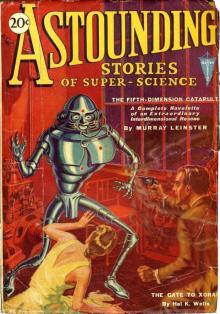

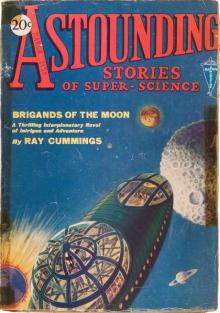

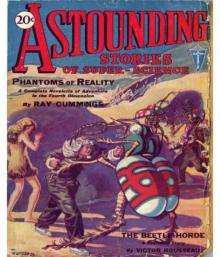

Astounding Stories, March, 1931

Astounding Stories, March, 1931 Astounding Stories, February, 1931

Astounding Stories, February, 1931 Futuria Fantasia, Spring 1940

Futuria Fantasia, Spring 1940 The King's Daughter and Other Stories for Girls

The King's Daughter and Other Stories for Girls Uncanny Tales

Uncanny Tales Masters of Noir: Volume Two

Masters of Noir: Volume Two Witty Pieces by Witty People

Witty Pieces by Witty People Sylvaneth

Sylvaneth Space Wolves

Space Wolves Hammerhal & Other Stories

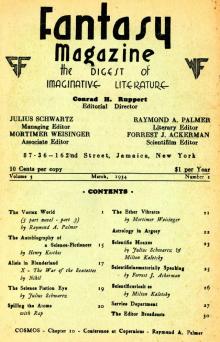

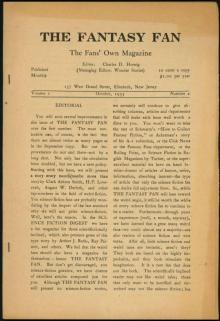

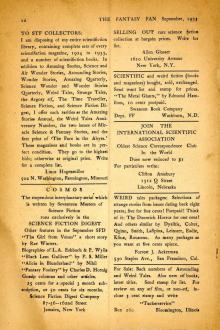

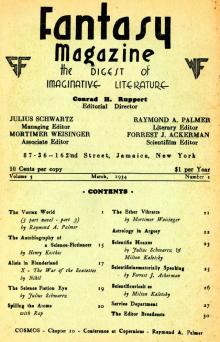

Hammerhal & Other Stories The Fantasy Fan, March, 1934

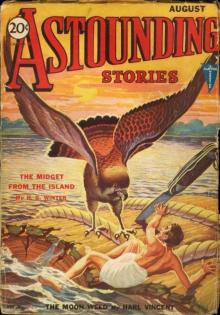

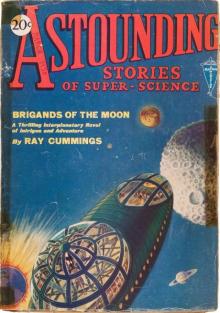

The Fantasy Fan, March, 1934 Astounding Stories of Super-Science, August 1930

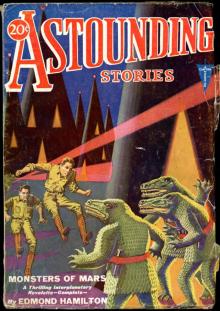

Astounding Stories of Super-Science, August 1930 Astounding Stories, August, 1931

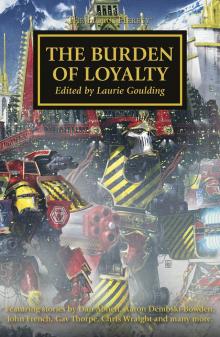

Astounding Stories, August, 1931 The Burden of Loyalty

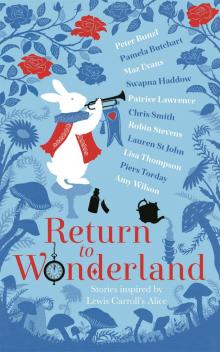

The Burden of Loyalty Return to Wonderland

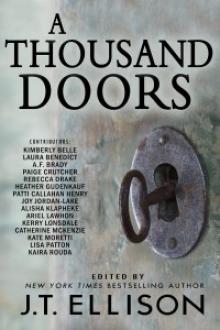

Return to Wonderland Anthology - A Thousand Doors

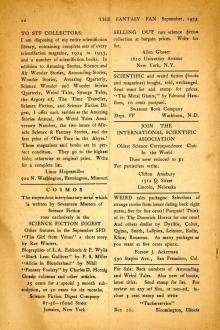

Anthology - A Thousand Doors The Fantasy Fan, October 1933

The Fantasy Fan, October 1933 Astounding Stories, June, 1931

Astounding Stories, June, 1931 Southern Stories

Southern Stories Astounding Stories of Super-Science, May, 1930

Astounding Stories of Super-Science, May, 1930 The Fantasy Fan December 1933

The Fantasy Fan December 1933 Adventures in Many Lands

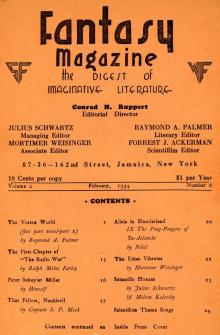

Adventures in Many Lands The Fantasy Fan February 1934

The Fantasy Fan February 1934 The Fantasy Fan November 1933

The Fantasy Fan November 1933 Astounding Stories, April, 1931

Astounding Stories, April, 1931 Fame and Fortune Weekly, No. 801, February 4, 1921

Fame and Fortune Weekly, No. 801, February 4, 1921 Astounding Stories of Super-Science, November, 1930

Astounding Stories of Super-Science, November, 1930 Astounding Stories of Super-Science January 1931

Astounding Stories of Super-Science January 1931 A Monk of Fife

A Monk of Fife Astounding Stories of Super-Science September 1930

Astounding Stories of Super-Science September 1930 Astounding Stories of Super-Science July 1930

Astounding Stories of Super-Science July 1930 Astounding Stories of Super-Science, June, 1930

Astounding Stories of Super-Science, June, 1930 Astounding Stories of Super-Science, October, 1930

Astounding Stories of Super-Science, October, 1930 Astounding Stories of Super-Science, March 1930

Astounding Stories of Super-Science, March 1930 The Fantasy Fan January 1934

The Fantasy Fan January 1934 The Fantasy Fan September 1933

The Fantasy Fan September 1933 Astounding Stories of Super-Science February 1930

Astounding Stories of Super-Science February 1930 Astounding Stories, May, 1931

Astounding Stories, May, 1931 Strange Stories of Colonial Days

Strange Stories of Colonial Days Golden Age of Science Fiction Vol IX

Golden Age of Science Fiction Vol IX Astounding Stories of Super-Science, December 1930

Astounding Stories of Super-Science, December 1930 Evolutions: Essential Tales of the Halo Universe

Evolutions: Essential Tales of the Halo Universe Good Stories Reprinted from the Ladies' Home Journal of Philadelphia

Good Stories Reprinted from the Ladies' Home Journal of Philadelphia Dragons!

Dragons! Murder Takes a Holiday

Murder Takes a Holiday Legacies of Betrayal

Legacies of Betrayal STAR WARS: TALES FROM THE CLONE WARS

STAR WARS: TALES FROM THE CLONE WARS Strange New Worlds 2016

Strange New Worlds 2016 Lippincott's Magazine, August, 1885

Lippincott's Magazine, August, 1885 Golden Age of Science Fiction Vol X

Golden Age of Science Fiction Vol X Hot Stuff

Hot Stuff Santa Wore Spurs

Santa Wore Spurs Paranormal Erotica

Paranormal Erotica Tangled Hearts: A Menage Collection

Tangled Hearts: A Menage Collection Sweet Tea and Jesus Shoes

Sweet Tea and Jesus Shoes The Journey Prize Stories 25

The Journey Prize Stories 25 Wild Western Tales 2: 101 Classic Western Stories Vol. 2 (Civitas Library Classics)

Wild Western Tales 2: 101 Classic Western Stories Vol. 2 (Civitas Library Classics) (5/15) The Golden Age of Science Fiction Volume V: An Anthology of 50 Short Stories

(5/15) The Golden Age of Science Fiction Volume V: An Anthology of 50 Short Stories (4/15) The Golden Age of Science Fiction Volume IV: An Anthology of 50 Short Stories

(4/15) The Golden Age of Science Fiction Volume IV: An Anthology of 50 Short Stories Ten Journeys

Ten Journeys The Boss

The Boss The Penguin Book of French Poetry

The Penguin Book of French Poetry Golden Age of Science Fiction Vol VIII

Golden Age of Science Fiction Vol VIII His Cinderella Housekeeper 3-in-1

His Cinderella Housekeeper 3-in-1 The Magazine of Fantasy & Science Fiction - July/August 2016

The Magazine of Fantasy & Science Fiction - July/August 2016 PYRATE CTHULHU - Tales of the Cthulhu Mythos (vol.2)

PYRATE CTHULHU - Tales of the Cthulhu Mythos (vol.2) Tales from a Master's Notebook

Tales from a Master's Notebook April 1930

April 1930 New Erotica 6

New Erotica 6 Damocles

Damocles The Longest Night Vol. 1

The Longest Night Vol. 1 The Golden Age of Science Fiction Volume VI: An Anthology of 50 Short Stories

The Golden Age of Science Fiction Volume VI: An Anthology of 50 Short Stories (1/15) The Golden Age of Science Fiction: An Anthology of 50 Short Stories

(1/15) The Golden Age of Science Fiction: An Anthology of 50 Short Stories Eye of Terra

Eye of Terra ONCE UPON A REGENCY CHRISTMAS

ONCE UPON A REGENCY CHRISTMAS Nexus Confessions

Nexus Confessions Passionate Kisses

Passionate Kisses War Without End

War Without End Doctor Who: Time Lord Fairy Tales

Doctor Who: Time Lord Fairy Tales Gotrek and Felix: The Anthology

Gotrek and Felix: The Anthology WESTERN CHRISTMAS PROPOSALS

WESTERN CHRISTMAS PROPOSALS The Journey Prize Stories 27

The Journey Prize Stories 27 The Silent War

The Silent War Liaisons

Liaisons Ellora's Cavemen: Tales from the Temple IV

Ellora's Cavemen: Tales from the Temple IV Ellora's Cavemen: Tales from the Temple II

Ellora's Cavemen: Tales from the Temple II Some of the Best From Tor.com, 2013 Edition: A Tor.Com Original

Some of the Best From Tor.com, 2013 Edition: A Tor.Com Original Urban Occult

Urban Occult Fractures

Fractures The Stories: Five Years of Original Fiction on Tor.com

The Stories: Five Years of Original Fiction on Tor.com The Penguin Book of Modern British Short Stories

The Penguin Book of Modern British Short Stories Mortarch of Night

Mortarch of Night The Portable Nineteenth-Century African American Women Writers

The Portable Nineteenth-Century African American Women Writers The Golden Age of Science Fiction Volume VII: An Anthology of 50 Short Stories

The Golden Age of Science Fiction Volume VII: An Anthology of 50 Short Stories Holy Bible: King James Version, The

Holy Bible: King James Version, The Eight Rooms

Eight Rooms sanguineangels

sanguineangels DarkNightsWithaBillionaireBundle

DarkNightsWithaBillionaireBundle Casserole Diplomacy and Other Stories

Casserole Diplomacy and Other Stories How I Survived My Summer Vacation

How I Survived My Summer Vacation Alfred Hitchcock Presents: 16 Skeletons From My Closet

Alfred Hitchcock Presents: 16 Skeletons From My Closet Lords, Ladies, Butlers and Maids

Lords, Ladies, Butlers and Maids The B4 Leg

The B4 Leg Ellora's Cavemen: Tales from the Temple I

Ellora's Cavemen: Tales from the Temple I 2014 Campbellian Anthology

2014 Campbellian Anthology There Is Only War

There Is Only War Obsidian Alliances

Obsidian Alliances 12 Gifts for Christmas

12 Gifts for Christmas Scary Holiday Tales to Make You Scream

Scary Holiday Tales to Make You Scream 25 For 25

25 For 25 The Plagues of Orath

The Plagues of Orath And Then He Kissed Me

And Then He Kissed Me Star Trek - Gateways 7 - WHAT LAY BEYOND

Star Trek - Gateways 7 - WHAT LAY BEYOND Laugh Your Head Off Again and Again

Laugh Your Head Off Again and Again The Balfour Legacy

The Balfour Legacy Golden Age of Science Fiction Vol XI

Golden Age of Science Fiction Vol XI (3/15) The Golden Age of Science Fiction Volume III: An Anthology of 50 Short Stories

(3/15) The Golden Age of Science Fiction Volume III: An Anthology of 50 Short Stories Shas'o

Shas'o Astounding Science Fiction Stories: An Anthology of 350 Scifi Stories Volume 2 (Halcyon Classics)

Astounding Science Fiction Stories: An Anthology of 350 Scifi Stories Volume 2 (Halcyon Classics) Twists in Time

Twists in Time Meduson

Meduson The Magazine of Fantasy & Science Fiction - August 1980

The Magazine of Fantasy & Science Fiction - August 1980 The Journey Prize Stories 22

The Journey Prize Stories 22 The Book that Made Me

The Book that Made Me Angels of Death Anthology

Angels of Death Anthology Ask the Bones

Ask the Bones Emergence

Emergence Beware the Little White Rabbit

Beware the Little White Rabbit Xcite Delights Book 1

Xcite Delights Book 1 Where flap the tatters of the King

Where flap the tatters of the King The Journey Prize Stories 21

The Journey Prize Stories 21 Tales of the Slayer, Volume II

Tales of the Slayer, Volume II Glass Empires

Glass Empires Golden Age of Science Fiction Vol XII

Golden Age of Science Fiction Vol XII (2/15) The Golden Age of Science Fiction Volume II: An Anthology of 50 Short Stories

(2/15) The Golden Age of Science Fiction Volume II: An Anthology of 50 Short Stories Fairytale Collection

Fairytale Collection Angels!

Angels! Golden Age of Science Fiction Vol XIII

Golden Age of Science Fiction Vol XIII