Evolutions: Essential Tales of the Halo Universe Read online

Page 2

The first thing was to have something to eat. He couldn’t get into the house for the food in there—he should have thought of that before stabbing his stepfather, should have taken some food out of the house and cached it in the woods. But it was too late for that now. He would have to make do.

At first he tried to catch an animal, one of the toothless squirrellike creatures that slid silently as ghosts around the trunks and boles of the trees. But after only a few minutes he realized they were much too fast for him. Next, he tried to sit motionless to see if they would come to him. They were curious and got close, but never quite close enough for him to grab one. Maybe he could kill one by throwing rocks? He tried, but mostly his aim was off, and the one time he hit one it simply gave an angry chitter and scuttled off. Even if I catch one, he suddenly realized, how am I going to cook it? I don’t have anything to start a fire.

What could he eat, then? Some of the plants were edible, but which ones? He wasn’t sure. His family had never harvested from the forest, sticking instead to their prepackaged provisions.

In the end he stepped on a dry, rotten branch and heard it crack, an eddy of bugs pouring out of the gap and quickly vanishing into the undergrowth. He heaved the branch over and saw, along the underside, pale white larvae, worms, large-jawed centipedes, and beetles spotted orange and blue. He avoided the beetles—if they were that brightly colored there must be something wrong with them—but tried both the larvae and the worms. The larvae had a nutty taste and were okay to eat if he didn’t think too much about them. The worms were a little slimier, but he could keep them down. When a few hours had passed and he didn’t feel sick, he turned over a few more fallen logs and ate his fill.

Before night fell he started to experiment, moving a little farther away from the house and making several beds out of the leaves and needles of different trees. One type of leaf, he found, raised a row of angry, itchy red bumps along his wrist when he touched it; he made a mental note of what it looked like and from then on avoided it. He tried each of the other beds in turn until he found one that was soft and a little warmer. He was still cold during the night, but no longer shivering. He was far from comfortable but he could stand it, and even sleep.

In just a few days, he had started to understand his patch of forest. He knew where to go for grubs, when to leave a log alone for a few days and when to turn it. Watching the ghost squirrels, he learned to avoid certain berries and plants. Others he tasted. Some were bitter and made him sick to his stomach and he didn’t return to them. But a few he went back to without any ill effect.

He watched his stepfather from the bushes. He was there to see him in the morning, when he came out of the house and went to the crops or to the processor that refined them into a white powder, and there to see him as well at night. Each time his stepfather left the house he carefully locked the door, and though Soren had tried a few times to break his way in, the windows were strong and he wasn’t successful.

Maybe I’ll make a trap, he began to think. Something his stepfather would step in or fall into or something that might fall on him and crush him. Could he do that?

He watched. His stepfather took the same route to the field every day, a straight and straightforward line along a dirt track his own feet had carved day after day. He was nothing if not predictable. The path was clear enough that there was little chance of hiding something on it or digging a hole without his noticing. Nor were there trees close enough to drop something from above.

Maybe it had been enough, he tried to tell himself. Maybe he could just forget about him and leave. But even though he told himself that, he found himself returning, day after day, to stare at the house. He was growing stronger, his young body lean and hard, nothing wasted. His hearing had grown keen, and his vision was such that he could now see the signs of when something had passed before him on the paths he traveled. When he was sure nothing and nobody was listening, he told himself stories, mumbled whispered fables, versions of things his mother had told him.

Several years later, thinking it over, he realized that he had become trapped, neither able to go into his house nor leave it behind completely. It was as though he was tethered to it, like a dog chained to a post. It might, he realized when he was older, have gone on indefinitely.

And indeed it did go on, Soren growing a little more wild each day, until something suddenly changed. One morning his stepfather came out and Soren could see there was something wrong with him. He was coughing badly, was hunched over—he was sick, Soren realized with a brief shudder of fear, in the same way Soren’s mother had been. His stepfather went to the crops, weaving slightly, but he was listless, exhausted, and by midday he had given up and was headed back. Only he didn’t make it all the way back. Halfway home, he fell to his knees and then laid there, flat on his stomach, his face pushing into the dirt, one leg jutted to the side. He was there a long time, unmoving. Soren thought he must be dead, but then as he watched his stepfather gave a shuddering breath and started to move again. But he didn’t go back to the house. Instead, he crawled his way to the truck and tried to pull himself into it.

When he failed and fell back into the dust, there was Soren, above him and a little way away, his face expressionless.

“Soren,” said his stepfather, his voice little above a whisper.

Soren didn’t say anything. He just stayed there without moving. Watching. Waiting.

“I thought you were dead,” said his stepfather. “I really did. I would have kept looking for you otherwise. Thank God you’re here.”

Soren folded his arms across his tiny chest.

“I need your help,” said his stepfather. “Help me get into the truck. I’m very sick. I need to find medicine.”

Still Soren said nothing, continuing to stand there motionless, waiting, not moving. He stayed like that, listening to his stepfather’s pleading, his growing panic, followed by threats and wheedling. Eventually the latter passed into unconsciousness. Then Soren sat down and stayed there, holding vigil over the sick man, until two days later his breathing stopped and he was dead. Then he reached into his stepfather’s pocket and took the keys and reclaimed the house.

IT WASN’T easy work to drag his mother out of the house and bury her, but in the end, his fingers blistered and bleeding from several days of slow digging, he managed. His stepfather he buried less from a sense of obligation and more because he wasn’t sure what else to do with the body. He liked to tell himself in later years that he had buried him to prove that he wasn’t like him, to prove he was more human, but he was never sure if that was the real reason. He buried him where he had fallen, just beside the truck, rolling him into a hole that was just deeper than the body and mounding the dirt high around him.

He stayed in the house for a few days, eating and building up his strength. When the provisions began to run low he finally managed to shake the house’s grip on him, walking out into the forest, making his way slowly in the direction that he thought a town might be. He was in the woods for days, maybe weeks, living off berries and grubs. Once he even managed to kill a ghost squirrel with a carefully thrown rock and then slit the fur off with another rock to eat the spongy, bitter meat within. After that, he stuck to berries and grubs.

And then, almost accidentally, he came across a track that he knew wasn’t made by an animal and followed it. A few hours later he found himself standing on the edge of a small township, startled by how the people stared at him when he emerged from the underbrush, his clothing tattered, his skin covered with dirt and grime. He was surprised by the way they rushed toward him, their faces creased with concern.

TWO

* * *

With such experience under his belt, life on Reach in the Spartan camp seemed less of a challenge to Soren than it did to many of the other recruits. After living in the woods alone, he felt he was ready for anything. He was quick to figure out the best way through an obstacle course. He could fade quickly into bushes and undergrowth when on mock

patrol. Camouflage was a way of life for him: He faded into the background too when in groups, wanting neither to come to attention as one of the leaders of a group nor to be seen as an outsider. He stuck to the anonymous middle.

But despite that, there were times when he noticed Dr. Halsey standing at a deliberate distance, watching him with an expression on her face that he could not interpret. Once, when he was nearly eleven, she even approached him as he ran through an exercise with the other children, standing at a slight remove, as he hesitated, wondering which team to join. He couldn’t decide if he was having trouble because she was scrutinizing him, or if he always waited until the last minute to make his choice and it just took her presence to make him realize it.

“Everything all right, Soren?” she asked him, her voice carefully modulated. Officially he was now Soren-66—a seemingly arbitrary digit for recruits, decided by the Office of Naval Intelligence for reasons they kept to themselves—but the doctor never called him by the number.

“Yes, sir,” he said, then realized she wasn’t a sir, or even, for that matter, a ma’am and blushed and looked guiltily at her. “Yes, Doctor?” he tried.

She smiled. “Don’t get distracted by irrelevant data,” she said to him, and then gestured idly past him, at the two teams already running for the skirmish ground. “And above all don’t let yourself get left behind.”

DON’T LET yourself get left behind. The words echoed for him not only through the rest of the exercise but for a long time to come, haunting him long after he was sure Dr. Halsey had forgotten them. There was, he slowly came to sense, something different about him, something that the other recruits either didn’t have or didn’t care to show. For that matter, he didn’t show it either: as he grew, he was very careful not to let anyone see anything that would make him different, would make him stand apart.

When he was very young, six or seven, he had been less careful. He hated sharing his room, found it exceptionally difficult to sleep hearing the sounds and the breathing of his fellow bunkmates. In their breathing he heard his stepfather. Sometimes he waited until they had fallen asleep and then slipped slowly out of his bed to hide under it, sleeping in the damp, musty space near the wall. He felt safer there. But when one morning he had slept late and hadn’t returned to his bed before the others had started waking up, the way they looked at him made him feel less safe. No, he would have to play along, would have to learn to go through the motions that all the others seemed to make so naturally. He wanted not so much to fit in as to fade in.

But after a while, it didn’t seem like an act anymore. He liked many aspects of the life of being a recruit. He enjoyed the challenge of it both mentally and physically. Having grown up off the grid, he had never been around people who were going through the same things he was; at times, particularly when they were darting through the forest together or crawling their breathless and silent way through a ditch full of mud, it was like being surrounded by many other versions of himself. It was comforting. Indeed, he felt closer to the other recruits than he had to anyone but his mother. Dr. Halsey, too, was the next best thing to a mother to him, though often distant, often preoccupied. But there was something about her that he found some strange kinship with.

He still needed time to himself, still found himself figuring out ways of being off on his own or, if not on his own, of creating a kind of momentary and temporary wall between himself and the others as a way of trying to think, to breathe, to be more fully himself. He realized very early on that he was never going to be a leader. He was not very communicative, but his instincts were honed and good and he was willing and able to follow orders. The others knew they could count on him. He felt in this the beginnings of a sense of meaning and purpose to his life, and he felt better than he had ever felt. He was keeping up. He wasn’t letting himself get left behind.

And yet he was still haunted by the past. Sometimes, particularly late at night, in the dark, he couldn’t help but think about what had happened when he was younger. He knew that whatever it was that made him different from the others came from that. At first the past was something he tried to push away, tried to forget, but as he grew older and smarter his thoughts about it became more and more conflicted. In his early teens, he began to see his stepfather less as a monster and more as someone who was scared and confused, somebody disastrously flawed, but someone who was also human. He fought against that realization, kept pushing it away, but it continually surged back over him. He had watched his stepfather die—it had been so quick, almost no time at all between the first symptoms and that strange transition from life to death. Which made him wonder, with a disease that moved that quickly: could his mother really have been saved?

All in all, he was neither the best nor the worst. He was a solid recruit and trainee, someone who, though haunted by his past, was doing his best to move beyond it. Perhaps, he thought, for the moment that was all he could ask for. Perhaps for now it was enough.

THREE

* * *

He was fourteen now, and standing at attention on the other side of Dr. Halsey’s desk. Her face, he noticed, was drawn and tight, her responses a little jerkier than usual, as if she hadn’t been getting enough sleep or was overworked. She hid it well, but Soren, himself an expert on hiding things well, saw all the cues he was learning to suppress in himself.

“At ease,” Dr. Halsey said. “Please take a seat, Soren.”

“Thank you, ma’am,” he said, and sat, a single fluid movement, nothing wasted.

She was whispering quietly to herself, scanning a series of electronic files. The files were holograms whose contents were visible to her but which he saw only as an image of a small brick wall, an image of CPO Mendez on the other side of it with his finger pressed to his lips. Someone has a weird sense of humor, he thought.

“Do you mind if I ask you a question?” she asked.

“Of course not, ma’am,” he said.

“Dr. Halsey,” she said. “No need to make me sound any older than I am. Do you remember when we first met?”

“Yes,” said Soren. Hardly a day had gone by without his thinking about that meeting and everything it had led to.

“I wonder, Soren, do you remember what I said, how I gave you a choice?”

Soren wrinkled his forehead briefly, then the lines cleared. “You mean whether to come with you or stay on Dwarka? Or was there something else?”

“No, just that,” she said. “You were young enough that I didn’t know how well you’d remember. How do you feel about your choice?”

“I’m glad I made it,” he said. “It was the right choice, ma’am.”

“I thought we already talked about your calling me that,” she said, smiling. “I wondered at the time whether I was right to give you a choice. Lieutenant Keyes wondered too. Whether you weren’t too young to have that burden placed on you.”

“Burden?” he asked.

She waved the implied question aside. “Never mind,” she said. “The reason I’ve brought you here is to give you another choice.”

He waited for her to continue, but for a moment she simply stayed there, staring at him, the same unreadable expression on her face that he’d noticed before, when he had caught her watching him during exercises.

“You’re still very young,” she said.

Soren said nothing.

Dr. Halsey sighed. “You’ve trained well, all of you. But training is only the first step. We’re on the verge of the second step. Would you like to take it?”

“What is it exactly?”

“There’s only so much I can tell you,” said Dr. Halsey. “There’s only so much the bodies that we have can do, Soren. So we want to augment them. We want to modify your physical body and mind to push it beyond normal human capabilities. We want to toughen your bones, increase your growth, build your muscle mass, sharpen your vision, improve your reflexes. We want to make you into the perfect soldier.” The smile that had been building on her face slowly faded a

way. “However, there will be side effects. Some of these we know, some we probably can’t anticipate. There’s also considerable risk.”

“What sort of risk?”

“There’s a chance, a nontrivial one, that you could die during the augmentation. Even if you don’t die, there’s a strong risk of Parkinson’s, Fletcher’s syndrome, and Ehlers-Danlos syndrome, as well as potential problems with deformation or atrophy of the muscles and degenerative bone conditions.”

He didn’t understand everything she was saying, but had the gist of it. “And if it works?”

“If it works, you’ll be stronger and faster than you can imagine.” She tented her fingers in front of her, staring over them at him. “I’m giving you an option that the others won’t be given. I am offering you a choice, while your classmates will simply be told they are to report for the procedure.”

“Why me?” asked Soren.

“Pardon?”

“Why am I the one who gets to make a choice? Why not one of the others?”

She turned her gaze to the desk in front of her, her voice distant now, more as if she were speaking to herself than the boy. “What the Spartans are is an experiment,” she said. “In every controlled experiment you need one sample whose conditions are different so as to be able to judge the progress of the larger group. You’re that sample, Soren.”

“We’re an experiment,” he said, his voice flat.

“I won’t lie to you. That is precisely what you are, and you—an experiment within the experiment. An exception to a rule,” she said.

“Why me?” he asked again. “You could have chosen anyone.”

She shrugged. “I don’t know, Soren. It just turned out that way.”

He was silent for a long time, staring straight in front of him, sorting it all out in his head. Finally he looked up.

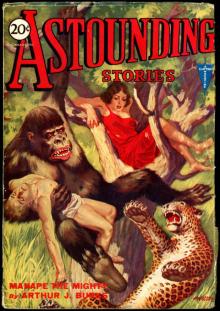

Astounding Stories, March, 1931

Astounding Stories, March, 1931 Astounding Stories, February, 1931

Astounding Stories, February, 1931 Futuria Fantasia, Spring 1940

Futuria Fantasia, Spring 1940 The King's Daughter and Other Stories for Girls

The King's Daughter and Other Stories for Girls Uncanny Tales

Uncanny Tales Masters of Noir: Volume Two

Masters of Noir: Volume Two Witty Pieces by Witty People

Witty Pieces by Witty People Sylvaneth

Sylvaneth Space Wolves

Space Wolves Hammerhal & Other Stories

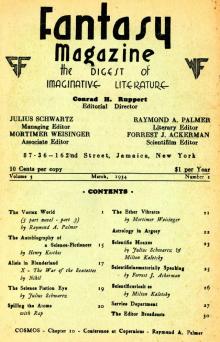

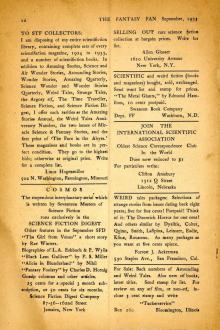

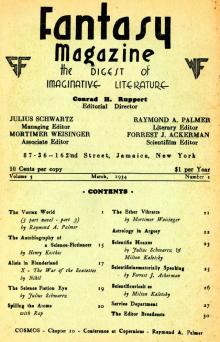

Hammerhal & Other Stories The Fantasy Fan, March, 1934

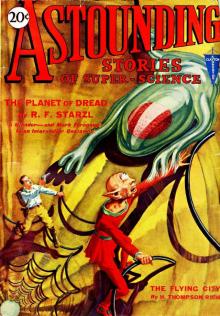

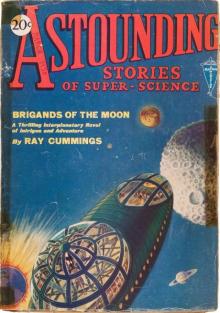

The Fantasy Fan, March, 1934 Astounding Stories of Super-Science, August 1930

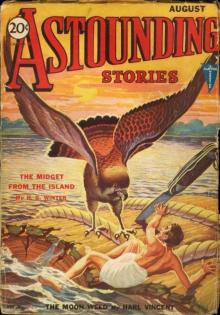

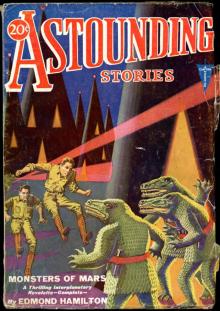

Astounding Stories of Super-Science, August 1930 Astounding Stories, August, 1931

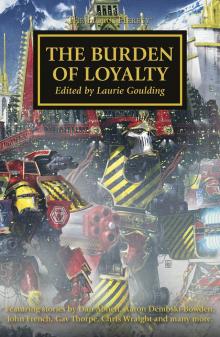

Astounding Stories, August, 1931 The Burden of Loyalty

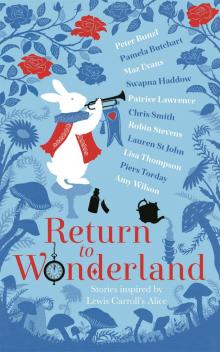

The Burden of Loyalty Return to Wonderland

Return to Wonderland Anthology - A Thousand Doors

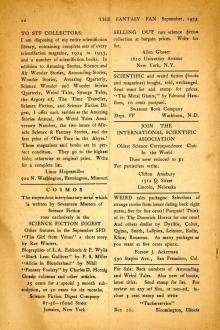

Anthology - A Thousand Doors The Fantasy Fan, October 1933

The Fantasy Fan, October 1933 Astounding Stories, June, 1931

Astounding Stories, June, 1931 Southern Stories

Southern Stories Astounding Stories of Super-Science, May, 1930

Astounding Stories of Super-Science, May, 1930 The Fantasy Fan December 1933

The Fantasy Fan December 1933 Adventures in Many Lands

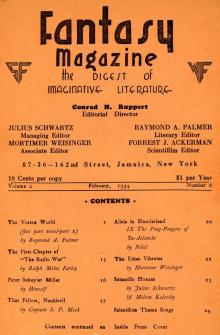

Adventures in Many Lands The Fantasy Fan February 1934

The Fantasy Fan February 1934 The Fantasy Fan November 1933

The Fantasy Fan November 1933 Astounding Stories, April, 1931

Astounding Stories, April, 1931 Fame and Fortune Weekly, No. 801, February 4, 1921

Fame and Fortune Weekly, No. 801, February 4, 1921 Astounding Stories of Super-Science, November, 1930

Astounding Stories of Super-Science, November, 1930 Astounding Stories of Super-Science January 1931

Astounding Stories of Super-Science January 1931 A Monk of Fife

A Monk of Fife Astounding Stories of Super-Science September 1930

Astounding Stories of Super-Science September 1930 Astounding Stories of Super-Science July 1930

Astounding Stories of Super-Science July 1930 Astounding Stories of Super-Science, June, 1930

Astounding Stories of Super-Science, June, 1930 Astounding Stories of Super-Science, October, 1930

Astounding Stories of Super-Science, October, 1930 Astounding Stories of Super-Science, March 1930

Astounding Stories of Super-Science, March 1930 The Fantasy Fan January 1934

The Fantasy Fan January 1934 The Fantasy Fan September 1933

The Fantasy Fan September 1933 Astounding Stories of Super-Science February 1930

Astounding Stories of Super-Science February 1930 Astounding Stories, May, 1931

Astounding Stories, May, 1931 Strange Stories of Colonial Days

Strange Stories of Colonial Days Golden Age of Science Fiction Vol IX

Golden Age of Science Fiction Vol IX Astounding Stories of Super-Science, December 1930

Astounding Stories of Super-Science, December 1930 Evolutions: Essential Tales of the Halo Universe

Evolutions: Essential Tales of the Halo Universe Good Stories Reprinted from the Ladies' Home Journal of Philadelphia

Good Stories Reprinted from the Ladies' Home Journal of Philadelphia Dragons!

Dragons! Murder Takes a Holiday

Murder Takes a Holiday Legacies of Betrayal

Legacies of Betrayal STAR WARS: TALES FROM THE CLONE WARS

STAR WARS: TALES FROM THE CLONE WARS Strange New Worlds 2016

Strange New Worlds 2016 Lippincott's Magazine, August, 1885

Lippincott's Magazine, August, 1885 Golden Age of Science Fiction Vol X

Golden Age of Science Fiction Vol X Hot Stuff

Hot Stuff Santa Wore Spurs

Santa Wore Spurs Paranormal Erotica

Paranormal Erotica Tangled Hearts: A Menage Collection

Tangled Hearts: A Menage Collection Sweet Tea and Jesus Shoes

Sweet Tea and Jesus Shoes The Journey Prize Stories 25

The Journey Prize Stories 25 Wild Western Tales 2: 101 Classic Western Stories Vol. 2 (Civitas Library Classics)

Wild Western Tales 2: 101 Classic Western Stories Vol. 2 (Civitas Library Classics) (5/15) The Golden Age of Science Fiction Volume V: An Anthology of 50 Short Stories

(5/15) The Golden Age of Science Fiction Volume V: An Anthology of 50 Short Stories (4/15) The Golden Age of Science Fiction Volume IV: An Anthology of 50 Short Stories

(4/15) The Golden Age of Science Fiction Volume IV: An Anthology of 50 Short Stories Ten Journeys

Ten Journeys The Boss

The Boss The Penguin Book of French Poetry

The Penguin Book of French Poetry Golden Age of Science Fiction Vol VIII

Golden Age of Science Fiction Vol VIII His Cinderella Housekeeper 3-in-1

His Cinderella Housekeeper 3-in-1 The Magazine of Fantasy & Science Fiction - July/August 2016

The Magazine of Fantasy & Science Fiction - July/August 2016 PYRATE CTHULHU - Tales of the Cthulhu Mythos (vol.2)

PYRATE CTHULHU - Tales of the Cthulhu Mythos (vol.2) Tales from a Master's Notebook

Tales from a Master's Notebook April 1930

April 1930 New Erotica 6

New Erotica 6 Damocles

Damocles The Longest Night Vol. 1

The Longest Night Vol. 1 The Golden Age of Science Fiction Volume VI: An Anthology of 50 Short Stories

The Golden Age of Science Fiction Volume VI: An Anthology of 50 Short Stories (1/15) The Golden Age of Science Fiction: An Anthology of 50 Short Stories

(1/15) The Golden Age of Science Fiction: An Anthology of 50 Short Stories Eye of Terra

Eye of Terra ONCE UPON A REGENCY CHRISTMAS

ONCE UPON A REGENCY CHRISTMAS Nexus Confessions

Nexus Confessions Passionate Kisses

Passionate Kisses War Without End

War Without End Doctor Who: Time Lord Fairy Tales

Doctor Who: Time Lord Fairy Tales Gotrek and Felix: The Anthology

Gotrek and Felix: The Anthology WESTERN CHRISTMAS PROPOSALS

WESTERN CHRISTMAS PROPOSALS The Journey Prize Stories 27

The Journey Prize Stories 27 The Silent War

The Silent War Liaisons

Liaisons Ellora's Cavemen: Tales from the Temple IV

Ellora's Cavemen: Tales from the Temple IV Ellora's Cavemen: Tales from the Temple II

Ellora's Cavemen: Tales from the Temple II Some of the Best From Tor.com, 2013 Edition: A Tor.Com Original

Some of the Best From Tor.com, 2013 Edition: A Tor.Com Original Urban Occult

Urban Occult Fractures

Fractures The Stories: Five Years of Original Fiction on Tor.com

The Stories: Five Years of Original Fiction on Tor.com The Penguin Book of Modern British Short Stories

The Penguin Book of Modern British Short Stories Mortarch of Night

Mortarch of Night The Portable Nineteenth-Century African American Women Writers

The Portable Nineteenth-Century African American Women Writers The Golden Age of Science Fiction Volume VII: An Anthology of 50 Short Stories

The Golden Age of Science Fiction Volume VII: An Anthology of 50 Short Stories Holy Bible: King James Version, The

Holy Bible: King James Version, The Eight Rooms

Eight Rooms sanguineangels

sanguineangels DarkNightsWithaBillionaireBundle

DarkNightsWithaBillionaireBundle Casserole Diplomacy and Other Stories

Casserole Diplomacy and Other Stories How I Survived My Summer Vacation

How I Survived My Summer Vacation Alfred Hitchcock Presents: 16 Skeletons From My Closet

Alfred Hitchcock Presents: 16 Skeletons From My Closet Lords, Ladies, Butlers and Maids

Lords, Ladies, Butlers and Maids The B4 Leg

The B4 Leg Ellora's Cavemen: Tales from the Temple I

Ellora's Cavemen: Tales from the Temple I 2014 Campbellian Anthology

2014 Campbellian Anthology There Is Only War

There Is Only War Obsidian Alliances

Obsidian Alliances 12 Gifts for Christmas

12 Gifts for Christmas Scary Holiday Tales to Make You Scream

Scary Holiday Tales to Make You Scream 25 For 25

25 For 25 The Plagues of Orath

The Plagues of Orath And Then He Kissed Me

And Then He Kissed Me Star Trek - Gateways 7 - WHAT LAY BEYOND

Star Trek - Gateways 7 - WHAT LAY BEYOND Laugh Your Head Off Again and Again

Laugh Your Head Off Again and Again The Balfour Legacy

The Balfour Legacy Golden Age of Science Fiction Vol XI

Golden Age of Science Fiction Vol XI (3/15) The Golden Age of Science Fiction Volume III: An Anthology of 50 Short Stories

(3/15) The Golden Age of Science Fiction Volume III: An Anthology of 50 Short Stories Shas'o

Shas'o Astounding Science Fiction Stories: An Anthology of 350 Scifi Stories Volume 2 (Halcyon Classics)

Astounding Science Fiction Stories: An Anthology of 350 Scifi Stories Volume 2 (Halcyon Classics) Twists in Time

Twists in Time Meduson

Meduson The Magazine of Fantasy & Science Fiction - August 1980

The Magazine of Fantasy & Science Fiction - August 1980 The Journey Prize Stories 22

The Journey Prize Stories 22 The Book that Made Me

The Book that Made Me Angels of Death Anthology

Angels of Death Anthology Ask the Bones

Ask the Bones Emergence

Emergence Beware the Little White Rabbit

Beware the Little White Rabbit Xcite Delights Book 1

Xcite Delights Book 1 Where flap the tatters of the King

Where flap the tatters of the King The Journey Prize Stories 21

The Journey Prize Stories 21 Tales of the Slayer, Volume II

Tales of the Slayer, Volume II Glass Empires

Glass Empires Golden Age of Science Fiction Vol XII

Golden Age of Science Fiction Vol XII (2/15) The Golden Age of Science Fiction Volume II: An Anthology of 50 Short Stories

(2/15) The Golden Age of Science Fiction Volume II: An Anthology of 50 Short Stories Fairytale Collection

Fairytale Collection Angels!

Angels! Golden Age of Science Fiction Vol XIII

Golden Age of Science Fiction Vol XIII