A Monk of Fife Read online

Page 2

CHAPTER I--HOW THIS BOOK WAS WRITTEN, AND HOW NORMAN LESLIE FLED OUT OFFIFE

It is not of my own will, nor for my own glory, that I, Norman Leslie,sometime of Pitcullo, and in religion called Brother Norman, of the Orderof Benedictines, of Dunfermline, indite this book. But on my coming outof France, in the year of our Lord One thousand four hundred and fifty-nine, it was laid on me by my Superior, Richard, Abbot in Dunfermline,that I should abbreviate the Great Chronicle of Scotland, and continuethe same down to our own time. {1} He bade me tell, moreover, all that Iknew of the glorious Maid of France, called Jeanne la Pucelle, in whosecompany I was, from her beginning even till her end.

Obedient, therefore, to my Superior, I wrote, in this our cell ofPluscarden, a Latin book containing the histories of times past, but whenI came to tell of matters wherein, as Maro says, "pars magna fui," I grewweary of such rude, barbarous Latin as alone I am skilled to indite, forof the manner Ciceronian, as it is now practised by clerks of Italy, I amnot master: my book, therefore, I left unfinished, breaking off in themiddle of a sentence. Yet, considering the command laid on me, in theend I am come to this resolve, namely, to write the history of the warsin France, and the history of the blessed Maid (so far at least as I wasan eyewitness and partaker thereof), in the French language, being themost commonly understood of all men, and the most delectable. It is notmy intent to tell all the story of the Maid, and all her deeds andsayings, for the world would scarcely contain the books that should bewritten. But what I myself beheld, that I shall relate, especiallyconcerning certain accidents not known to the general, by reason of whichignorance the whole truth can scarce be understood. For, if Heavenvisibly sided with France and the Maid, no less did Hell most manifestlytake part with our old enemy of England. And often in this life, if welook not the more closely, and with the eyes of faith, Sathanas shallseem to have the upper hand in the battle, with whose very imp and minionI myself was conversant, to my sorrow, as shall be shown.

First, concerning myself I must say some few words, to the end that whatfollows may be the more readily understood.

I was born in the kingdom of Fife, being, by some five years, the youngerof two sons of Archibald Leslie, of Pitcullo, near St. Andrews, a cadetof the great House of Rothes. My mother was an Englishwoman of theDebatable Land, a Storey of Netherby, and of me, in our country speech,it used to be said that I was "a mother's bairn." For I had ever mygreatest joy in her, whom I lost ere I was sixteen years of age, and shein me: not that she favoured me unduly, for she was very just, but that,within ourselves, we each knew who was nearest to her heart. She was,indeed, a saintly woman, yet of a merry wit, and she had great pleasurein reading of books, and in romances. Being always, when I might, in hercompany, I became a clerk insensibly, and without labour I could earlyread and write, wherefore my father was minded to bring me up for achurchman. For this cause, I was some deal despised by others of my age,and, yet more, because from my mother I had caught the Southron trick ofthe tongue. They called me "English Norman," and many a battle I havefought on that quarrel, for I am as true a Scot as any, and I hated theEnglish (my own mother's people though they were) for taking and holdingcaptive our King, James I. of worthy memory. My fancy, like that of mostboys, was all for the wars, and full of dreams concerning knights andladies, dragons and enchanters, about which the other lads were fainenough to hear me tell what I had read in romances, though they mocked atme for reading. Yet they oft came ill speed with their jests, for mybrother had taught me to use my hands: and to hold a sword I wasinstructed by our smith, who had been prentice to Harry Gow, the Burn-the-Wind of Perth, and the best man at his weapon in broad Scotland. Fromhim I got many a trick of fence that served my turn later.

But now the evil time came when my dear mother sickened and died, leavingto me her memory and her great chain of gold. A bitter sorrow is herdeath to me still; but anon my father took to him another wife of theBethunes of Blebo. I blame myself, rather than this lady, that we dweltnot happily in the same house. My father therefore, still minded to makeme a churchman, sent me to Robert of Montrose's new college that standsin the South Street of St. Andrews, a city not far from our house ofPitcullo. But there, like a wayward boy, I took more pleasure in thebattles of the "nations"--as of Fife against Galloway and the Lennox; orin games of catch-pull, football, wrestling, hurling the bar, archery,and golf--than in divine learning--as of logic, and Aristotle hisanalytics.

Yet I loved to be in the scriptorium of the Abbey, and to see the goodFather Peter limning the blessed saints in blue, and red, and gold, ofwhich art he taught me a little. Often I would help him to grind hiscolours, and he instructed me in the laying of them on paper or vellum,with white of egg, and in fixing and burnishing the gold, and in drawingflowers, and figures, and strange beasts and devils, such as we seegrinning from the walls of the cathedral. In the French language, too,he learned me, for he had been taught at the great University of Paris;and in Avignon had seen the Pope himself, Benedict XIII., of uncertainmemory.

Much I loved to be with Father Peter, whose lessons did not irk me, butjumped with my own desire to read romances in the French tongue, whereofthere are many. But never could I have dreamed that, in days to come,this art of painting would win me my bread for a while, and that a Leslieof Pitcullo should be driven by hunger to so base and contemned ahandiwork, unworthy, when practised for gain, of my blood.

Yet it would have been well for me to follow even this craft more, and mysports and pastimes less: Dickon Melville had then escaped a broken head,and I, perchance, a broken heart. But youth is given over to vanitiesthat war against the soul, and, among others, to that wicked game of theGolf, now justly cried down by our laws, {2} as the mother of cursing andidleness, mischief and wastery, of which game, as I verily believe, thedevil himself is the father.

It chanced, on an October day of the year of grace Fourteen hundred andtwenty-eight, that I was playing myself at this accursed sport with oneRichard Melville, a student of like age with myself. We were evenlymatched, though Dickon was tall and weighty, being great of growth forhis age, whereas I was of but scant inches, slim, and, as men said, of agirlish countenance. Yet I was well skilled in the game of the Golf, andhave driven a Holland ball the length of an arrow-flight, there orthereby. But wherefore should my sinful soul be now in mind of these oldvanities, repented of, I trust, long ago?

As we twain, Dickon and I, were known for fell champions at this unholysport, many of the other scholars followed us, laying wagers on ourheads. They were but a wild set of lads, for, as then, there was not, asnow there is, a house appointed for scholars to dwell in together underauthority. We wore coloured clothes, and our hair long; gold chains, andwhingers {3} in our belts, all of which things are now most righteouslyforbidden. But I carried no whinger on the links, as considering that ithampered a man in his play. So the game went on, now Dickon leading "bya hole," as they say, and now myself, and great wagers were laid on us.

Now, at the hole that is set high above the Eden, whence you see far overthe country, and the river-mouth, and the shipping, it chanced that myball lay between Dickon's and the hole, so that he could in no manner winpast it.

"You laid me that stimy of set purpose," cried Dickon, throwing down hisclub in a rage; "and this is the third time you have done it in thisgame."

"It is clean against common luck," quoth one of his party, "and the gameand the money laid on it should be ours."

"By the blessed bones of the Apostle," I said, "no luck is more common.To-day to me, to-morrow to thee! Lay it of purpose, I could not if Iwould."

"You lie!" he shouted in a rage, and gripped to his whinger.

It was ever my father's counsel that I must take the lie from none.Therefore, as his steel was out, and I carried none, I made no more ado,and the word of shame had scarce left his lips when I felled him with theiron club that we use in sand.

"He is dead!" cried they of his party, while the lads of my own lookedaska

nce on me, and had manifestly no mind to be partakers in my deed.

Now, Melville came of a great house, and, partly in fear of their feud,partly like one amazed and without any counsel, I ran and leaped into aboat that chanced to lie convenient on the sand, and pulled out into theEden. Thence I saw them raise up Melville, and bear him towards thetown, his friends lifting their hands against me, with threats andmalisons. His legs trailed and his head wagged like the legs and thehead of a dead man, and I was without hope in the world.

At first it was my thought to row up the river-mouth, land, and makeacross the marshes and fields to our house at Pitcullo. But I bethoughtme that my father was an austere man, whom I had vexed beyond bearingwith my late wicked follies, into which, since the death of my mother, Ihad fallen. And now I was bringing him no college prize, but a blood-feud, which he was like to find an ill heritage enough, even without anevil and thankless son. My stepmother, too, who loved me little, wouldinflame his anger against me. Many daughters he had, and of gear andgoods no more than enough. Robin, my elder brother, he had let pass toFrance, where he served among the men of John Kirkmichael, Bishop ofOrleans--he that smote the Duke of Clarence in fair fight at Bauge.

Thinking of my father, and of my stepmother's ill welcome, and of Robin,abroad in the wars against our old enemy of England, it may be that Ifell into a kind of half dream, the boat lulling me by its movement onthe waters. Suddenly I felt a crashing blow on my head. It was as ifthe powder used for artillery had exploded in my mouth, with flash oflight and fiery taste, and I knew nothing. Then, how long after I couldnot tell, there was water on my face, the blue sky and the blue tide werespinning round--they spun swiftly, then slowly, then stood still. Therewas a fierce pain stounding in my head, and a voice said--

"That good oar-stroke will learn you to steal boats!"

I knew the voice; it was that of a merchant sailor-man with whom, on theday before, I had quarrelled in the market-place. Now I was lying at thebottom of a boat which four seamen, who had rowed up to me and had brokenmy head as I meditated, were pulling towards a merchant-vessel, orcarrick, in the Eden-mouth. Her sails were being set; the boat wherein Ilay was towing that into which I had leaped after striking down Melville.For two of the ship's men, being on shore, had hailed their fellows inthe carrick, and they had taken vengeance upon me.

"You scholar lads must be taught better than your masters learn you,"said my enemy.

And therewith they carried me on board the vessel, the "St. Margaret," ofBerwick, laden with a cargo of dried salmon from Eden-mouth. They meantme no kindness, for there was an old feud between the scholars and thesailors; but it seemed to me, in my foolishness, that now I was in luck'sway. I need not go back, with blood on my hands, to Pitcullo and myfather. I had money in my pouch, my mother's gold chain about my neck, aship's deck under my foot, and the seas before me. It was not hard forme to bargain with the shipmaster for a passage to Berwick, whence Imight put myself aboard a vessel that traded to Bordeaux for wine fromthat country. The sailors I made my friends at no great cost, for indeedthey were the conquerors, and could afford to show clemency, and hold meto slight ransom as a prisoner of war.

So we lifted anchor, and sailed out of Eden-mouth, none of those on shoreknowing how I was aboard the carrick that slipped by the bishop's castle,and so under the great towers of the minster and St. Rule's, forth to theNorthern Sea. Despite my broken head--which put it comfortably into mymind that maybe Dickon's was no worse--I could have laughed to think howclean I had vanished away from St. Andrews, as if the fairies had takenme. Now having time to reason of it quietly, I picked up hope forDickon's life, remembering his head to be of the thickest. Then cameinto my mind the many romances of chivalry which I had read, wherein theyoung squire has to flee his country for a chance blow, as did MessirePatroclus, in the Romance of Troy, who slew a man in anger over the gameof the chess, and many another knight, in the tales of Charlemagne andhis paladins. For ever it is thus the story opens, and my story,methought, was beginning to-day like the rest.

Now, not to prove more wearisome than need be, and so vex those who readthis chronicle with much talk about myself, and such accidents of travelas beset all voyagers, and chiefly in time of war, I found a trading shipat Berwick, and reached Bordeaux safe, after much sickness on the sea.And in Bordeaux, with a very sore heart, I changed the links of mymother's chain that were left to me--all but four, that still I keep--formoney of that country; and so, with a lighter pack than spirit, I setforth towards Orleans and to my brother Robin.

On this journey I had good cause to bless Father Peter of the Abbey forhis teaching me the French tongue, that was of more service to me thanall my Latin. Yet my Latin, too, the little I knew, stood me in goodstead at the monasteries, where often I found bed and board, and no smallkindness; I little deeming that, in time to come, I also should be inreligion, an old man and weary, glad to speak with travellers concerningthe news of the world, from which I am now these ten years retired. YetI love even better to call back memories of these days, when I took mypart in the fray. If this be a sin, may God and the Saints forgive me,for if I have fought, it was in a rightful cause, which Heaven at lasthas prospered, and in no private quarrel. And methinks I have one amongthe Saints to pray for me, as a friend for a friend not unfaithful. Buton this matter I submit me to the judgment of the Church, as in allquestions of the faith.

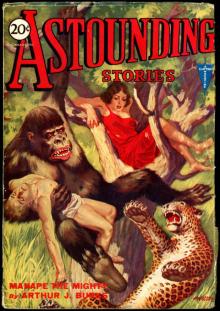

Astounding Stories, March, 1931

Astounding Stories, March, 1931 Astounding Stories, February, 1931

Astounding Stories, February, 1931 Futuria Fantasia, Spring 1940

Futuria Fantasia, Spring 1940 The King's Daughter and Other Stories for Girls

The King's Daughter and Other Stories for Girls Uncanny Tales

Uncanny Tales Masters of Noir: Volume Two

Masters of Noir: Volume Two Witty Pieces by Witty People

Witty Pieces by Witty People Sylvaneth

Sylvaneth Space Wolves

Space Wolves Hammerhal & Other Stories

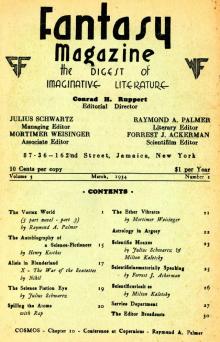

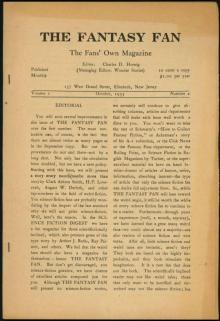

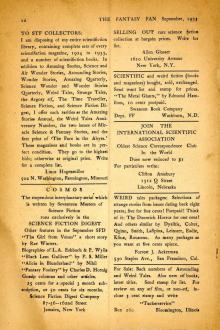

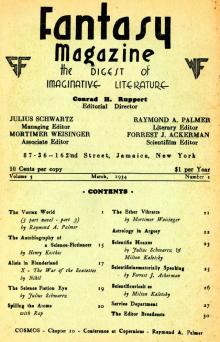

Hammerhal & Other Stories The Fantasy Fan, March, 1934

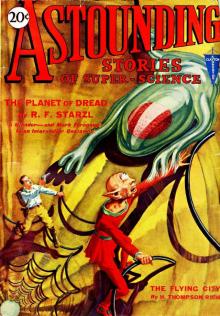

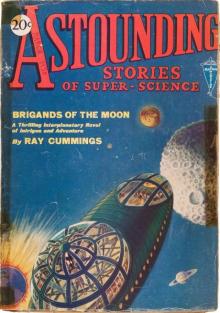

The Fantasy Fan, March, 1934 Astounding Stories of Super-Science, August 1930

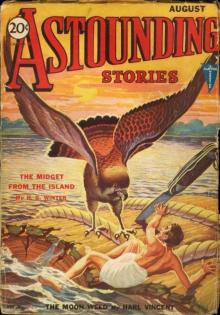

Astounding Stories of Super-Science, August 1930 Astounding Stories, August, 1931

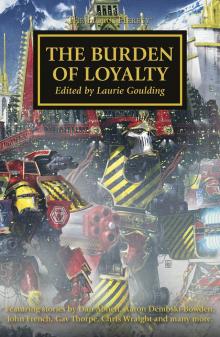

Astounding Stories, August, 1931 The Burden of Loyalty

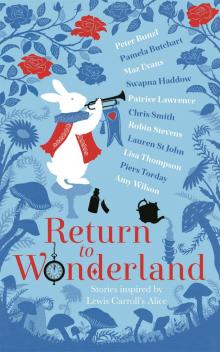

The Burden of Loyalty Return to Wonderland

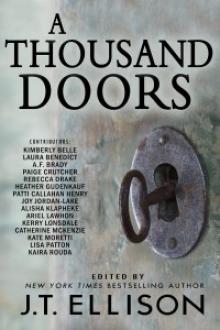

Return to Wonderland Anthology - A Thousand Doors

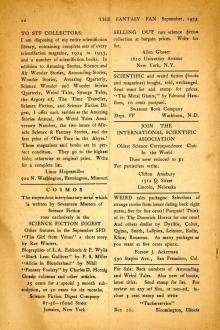

Anthology - A Thousand Doors The Fantasy Fan, October 1933

The Fantasy Fan, October 1933 Astounding Stories, June, 1931

Astounding Stories, June, 1931 Southern Stories

Southern Stories Astounding Stories of Super-Science, May, 1930

Astounding Stories of Super-Science, May, 1930 The Fantasy Fan December 1933

The Fantasy Fan December 1933 Adventures in Many Lands

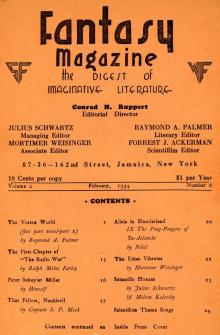

Adventures in Many Lands The Fantasy Fan February 1934

The Fantasy Fan February 1934 The Fantasy Fan November 1933

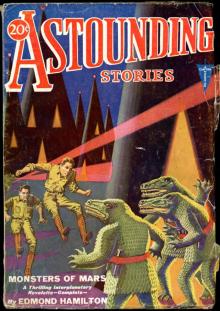

The Fantasy Fan November 1933 Astounding Stories, April, 1931

Astounding Stories, April, 1931 Fame and Fortune Weekly, No. 801, February 4, 1921

Fame and Fortune Weekly, No. 801, February 4, 1921 Astounding Stories of Super-Science, November, 1930

Astounding Stories of Super-Science, November, 1930 Astounding Stories of Super-Science January 1931

Astounding Stories of Super-Science January 1931 A Monk of Fife

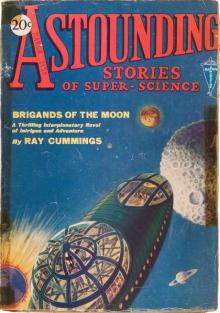

A Monk of Fife Astounding Stories of Super-Science September 1930

Astounding Stories of Super-Science September 1930 Astounding Stories of Super-Science July 1930

Astounding Stories of Super-Science July 1930 Astounding Stories of Super-Science, June, 1930

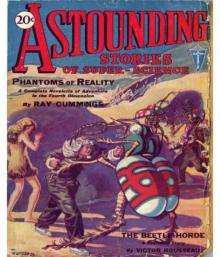

Astounding Stories of Super-Science, June, 1930 Astounding Stories of Super-Science, October, 1930

Astounding Stories of Super-Science, October, 1930 Astounding Stories of Super-Science, March 1930

Astounding Stories of Super-Science, March 1930 The Fantasy Fan January 1934

The Fantasy Fan January 1934 The Fantasy Fan September 1933

The Fantasy Fan September 1933 Astounding Stories of Super-Science February 1930

Astounding Stories of Super-Science February 1930 Astounding Stories, May, 1931

Astounding Stories, May, 1931 Strange Stories of Colonial Days

Strange Stories of Colonial Days Golden Age of Science Fiction Vol IX

Golden Age of Science Fiction Vol IX Astounding Stories of Super-Science, December 1930

Astounding Stories of Super-Science, December 1930 Evolutions: Essential Tales of the Halo Universe

Evolutions: Essential Tales of the Halo Universe Good Stories Reprinted from the Ladies' Home Journal of Philadelphia

Good Stories Reprinted from the Ladies' Home Journal of Philadelphia Dragons!

Dragons! Murder Takes a Holiday

Murder Takes a Holiday Legacies of Betrayal

Legacies of Betrayal STAR WARS: TALES FROM THE CLONE WARS

STAR WARS: TALES FROM THE CLONE WARS Strange New Worlds 2016

Strange New Worlds 2016 Lippincott's Magazine, August, 1885

Lippincott's Magazine, August, 1885 Golden Age of Science Fiction Vol X

Golden Age of Science Fiction Vol X Hot Stuff

Hot Stuff Santa Wore Spurs

Santa Wore Spurs Paranormal Erotica

Paranormal Erotica Tangled Hearts: A Menage Collection

Tangled Hearts: A Menage Collection Sweet Tea and Jesus Shoes

Sweet Tea and Jesus Shoes The Journey Prize Stories 25

The Journey Prize Stories 25 Wild Western Tales 2: 101 Classic Western Stories Vol. 2 (Civitas Library Classics)

Wild Western Tales 2: 101 Classic Western Stories Vol. 2 (Civitas Library Classics) (5/15) The Golden Age of Science Fiction Volume V: An Anthology of 50 Short Stories

(5/15) The Golden Age of Science Fiction Volume V: An Anthology of 50 Short Stories (4/15) The Golden Age of Science Fiction Volume IV: An Anthology of 50 Short Stories

(4/15) The Golden Age of Science Fiction Volume IV: An Anthology of 50 Short Stories Ten Journeys

Ten Journeys The Boss

The Boss The Penguin Book of French Poetry

The Penguin Book of French Poetry Golden Age of Science Fiction Vol VIII

Golden Age of Science Fiction Vol VIII His Cinderella Housekeeper 3-in-1

His Cinderella Housekeeper 3-in-1 The Magazine of Fantasy & Science Fiction - July/August 2016

The Magazine of Fantasy & Science Fiction - July/August 2016 PYRATE CTHULHU - Tales of the Cthulhu Mythos (vol.2)

PYRATE CTHULHU - Tales of the Cthulhu Mythos (vol.2) Tales from a Master's Notebook

Tales from a Master's Notebook April 1930

April 1930 New Erotica 6

New Erotica 6 Damocles

Damocles The Longest Night Vol. 1

The Longest Night Vol. 1 The Golden Age of Science Fiction Volume VI: An Anthology of 50 Short Stories

The Golden Age of Science Fiction Volume VI: An Anthology of 50 Short Stories (1/15) The Golden Age of Science Fiction: An Anthology of 50 Short Stories

(1/15) The Golden Age of Science Fiction: An Anthology of 50 Short Stories Eye of Terra

Eye of Terra ONCE UPON A REGENCY CHRISTMAS

ONCE UPON A REGENCY CHRISTMAS Nexus Confessions

Nexus Confessions Passionate Kisses

Passionate Kisses War Without End

War Without End Doctor Who: Time Lord Fairy Tales

Doctor Who: Time Lord Fairy Tales Gotrek and Felix: The Anthology

Gotrek and Felix: The Anthology WESTERN CHRISTMAS PROPOSALS

WESTERN CHRISTMAS PROPOSALS The Journey Prize Stories 27

The Journey Prize Stories 27 The Silent War

The Silent War Liaisons

Liaisons Ellora's Cavemen: Tales from the Temple IV

Ellora's Cavemen: Tales from the Temple IV Ellora's Cavemen: Tales from the Temple II

Ellora's Cavemen: Tales from the Temple II Some of the Best From Tor.com, 2013 Edition: A Tor.Com Original

Some of the Best From Tor.com, 2013 Edition: A Tor.Com Original Urban Occult

Urban Occult Fractures

Fractures The Stories: Five Years of Original Fiction on Tor.com

The Stories: Five Years of Original Fiction on Tor.com The Penguin Book of Modern British Short Stories

The Penguin Book of Modern British Short Stories Mortarch of Night

Mortarch of Night The Portable Nineteenth-Century African American Women Writers

The Portable Nineteenth-Century African American Women Writers The Golden Age of Science Fiction Volume VII: An Anthology of 50 Short Stories

The Golden Age of Science Fiction Volume VII: An Anthology of 50 Short Stories Holy Bible: King James Version, The

Holy Bible: King James Version, The Eight Rooms

Eight Rooms sanguineangels

sanguineangels DarkNightsWithaBillionaireBundle

DarkNightsWithaBillionaireBundle Casserole Diplomacy and Other Stories

Casserole Diplomacy and Other Stories How I Survived My Summer Vacation

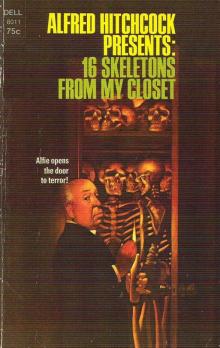

How I Survived My Summer Vacation Alfred Hitchcock Presents: 16 Skeletons From My Closet

Alfred Hitchcock Presents: 16 Skeletons From My Closet Lords, Ladies, Butlers and Maids

Lords, Ladies, Butlers and Maids The B4 Leg

The B4 Leg Ellora's Cavemen: Tales from the Temple I

Ellora's Cavemen: Tales from the Temple I 2014 Campbellian Anthology

2014 Campbellian Anthology There Is Only War

There Is Only War Obsidian Alliances

Obsidian Alliances 12 Gifts for Christmas

12 Gifts for Christmas Scary Holiday Tales to Make You Scream

Scary Holiday Tales to Make You Scream 25 For 25

25 For 25 The Plagues of Orath

The Plagues of Orath And Then He Kissed Me

And Then He Kissed Me Star Trek - Gateways 7 - WHAT LAY BEYOND

Star Trek - Gateways 7 - WHAT LAY BEYOND Laugh Your Head Off Again and Again

Laugh Your Head Off Again and Again The Balfour Legacy

The Balfour Legacy Golden Age of Science Fiction Vol XI

Golden Age of Science Fiction Vol XI (3/15) The Golden Age of Science Fiction Volume III: An Anthology of 50 Short Stories

(3/15) The Golden Age of Science Fiction Volume III: An Anthology of 50 Short Stories Shas'o

Shas'o Astounding Science Fiction Stories: An Anthology of 350 Scifi Stories Volume 2 (Halcyon Classics)

Astounding Science Fiction Stories: An Anthology of 350 Scifi Stories Volume 2 (Halcyon Classics) Twists in Time

Twists in Time Meduson

Meduson The Magazine of Fantasy & Science Fiction - August 1980

The Magazine of Fantasy & Science Fiction - August 1980 The Journey Prize Stories 22

The Journey Prize Stories 22 The Book that Made Me

The Book that Made Me Angels of Death Anthology

Angels of Death Anthology Ask the Bones

Ask the Bones Emergence

Emergence Beware the Little White Rabbit

Beware the Little White Rabbit Xcite Delights Book 1

Xcite Delights Book 1 Where flap the tatters of the King

Where flap the tatters of the King The Journey Prize Stories 21

The Journey Prize Stories 21 Tales of the Slayer, Volume II

Tales of the Slayer, Volume II Glass Empires

Glass Empires Golden Age of Science Fiction Vol XII

Golden Age of Science Fiction Vol XII (2/15) The Golden Age of Science Fiction Volume II: An Anthology of 50 Short Stories

(2/15) The Golden Age of Science Fiction Volume II: An Anthology of 50 Short Stories Fairytale Collection

Fairytale Collection Angels!

Angels! Golden Age of Science Fiction Vol XIII

Golden Age of Science Fiction Vol XIII