PYRATE CTHULHU - Tales of the Cthulhu Mythos (vol.2) Read online

Page 21

It got so bad I fell down on my knees and pressed my hands hard to my ears. I cried there, real, gushin’ tears. I felt so lonely, like that patch of dirt road beneath me was the only piece of land there was left, and I was fallin’ down a deep hole with no walls or bottom to be seent. I couldn’t summon no prayers.

I don’t know how long I knelt there, but all of a sudden the pickup’s headlights come back on, bright. I brushed my eyes and stood up, blind, still afraid.

Yeller was standin’ at the edge of the light. The stars was out again and the moon was bright over his head, as if they’d all been hidin’ from the shadow man. The moonlight was gleamin’ kinda green on the face of Yeller’s National.

Yeller’s eyes was half closed and he was shinin’ all over with sweat. He looked like a horse addict. That rascal light was gone from him.

“Let’s get outta here, Harp,” he said, and he went to where the Catalina was.

“What ‘bout these…,” I started to say ‘peckerwoods,’ but when I looked, they wasn’t no bodies in the road, just a couple butter yellow and black burn marks. They was a smell in the air like to make me sick, like a open sewer stuffed with dead dogs. I followed him to the car.

***

Yeller’s fingers wouldn’t leave his National alone the whole ride back. The sounds comin’ out of it was like slippery chain lightnin’. I never heard nobody play a guitar like he did the ride back to Ruleville. The shadow man had made him natural born. He didn’t say a word, just stared at the white line of the road as the car sucked it outta the dark ahead.

I noticed they was somethin’ different ‘bout his guitar, too. The tunin’ knobs had been chewed by mice, he told me, but they looked brand new now. They wasn’t a mark of rust or tarnish now either, and the steel felt strange. It was warm to the touch, and they was trace marks all over the backside, so faint you could only see ‘em close. They was shapes, or pictures, but of what I couldn’t say. Animals, or fish maybe, but none I could place. I didn’t like ‘em.

***

We stayed at a flophouse, and the next mornin’, and every mornin’ for the next week, Yeller went out to Greasy Street and cut heads. This time wasn’t nobody in sight that didn’t come over to hear him play, and some even come down outta the shops and the houses to listen. It got to be so’s nobody else played when Yeller was on the scene.

At night, we went from juke to juke. Yeller brought ‘em in like the Pied Piper. He played the Flowerin’ Fountain, Po Monkey’s, Red’s, JJ’s…we drove all over the Delta, and folks lined up outside to see him. He really lit them up, too. The belly rubbin’, the howlin’, it was on whenever Yeller played. Some said Robert Johnson had beat the devil and come back. They was a fight without fail anytime he played. Sometimes it would get real bad. I seent a man cut up his woman’s face with a razor at one show. Once, two men shot each other dead, right in the street out front.

Yeller never said nothin’ ‘bout this. They wasn’t no joy in him no more. He hardly ever smiled, an’ never sang out to no girls, though they did they best to get him to notice. He drank a lot, and when his set was up, all he wanted to do was hit the road.

His songs got strange too. Space Dog Blues, House Underwater, Black Goat Blues, they was all ‘bout darkness and dyin’ alone. Sometimes I didn’t even know what they was ‘bout, he jumbled up his words so bad. Nobody cared. It was that sound they loved.

I ‘member he did one called Cut Through You Sleepin’. I think it was ‘bout a man killin’ his woman in bed. The only words I could make out was:

What ain’t dead can keep a’layin’ – yas,

And come the judgment day even death might pass.

He’d always finish it with this sound, halfway between a sneeze and one of them Cuban big band shouts. F’uagh, or f’tagh.

Yeller hardly talked. After shows, he’d just set on the edge of his bed with a whiskey and drink, starin’ out the window till he passed out. He slept all day and I had to tell him to eat.

Then white men started showin’ up to his shows. They’d ask him if he never thought ‘bout recordin’. I know that’s what he wanted, but weeks went by of that and he always said no.

He might’ve been the biggest they ever was. Might’ve even saved the blues from them damn Beatles, ‘cept for The Crawlin’ Chaos Blues.

***

One Friday night outside of Clarkesdale, I asked him when he planned on layin’ tracks, and did he want to go back to Chicago, maybe see if he could get a deal with Chess Records.

He looked at me with them spacey, scarecrow eyes, and he said, “How come you never asked me ‘bout the shadow man, Harp?”

I told him I didn’t want to talk ‘bout that. I didn’t like to remember it.

“You can see what he done for me, can’t you?” said Yeller. “You ain’t never asked me what I paid him.”

“I know what you paid,” I said, meanin’ the two white boys.

“No, you don’t,” he said.

“He ask for your soul?”

“My soul…I wish I had one. He ain’t the devil, Harp. Maybe they ain’t no devil. He showed me things. Things ain’t nobody got no business knowin’. You know, I wanted this so bad, I was goin’ to kill you that night. I thought I wanted more than chicken blood woulda got me, you know?”

I didn’t know what to say to that.

He was quiet, and he drank, then he said, “He took somethin’ from me I can’t never get back. He gimme what I need to be great, but I can’t.”

“Whatchoo mean?”

“Say a man build you a house, but he leave the roof off, and he tell you if you put one up yourself, the whole thing goin’ fall down on your head while you sleepin’. Whatchoo got, then? When the rain come, whatchoo got?”

I still didn’t know what he was talkin’ ‘bout, and he could see.

“Look. The shadow man put all these songs in my head, but then he gimme one song,” and he closed his eyes and smiled just a little, like he was thinkin’ of somethin’ sweet, “the best song anybody ever heard.” Then he opened his eyes, and that dead look come back, like happiness had excused hisself and got off at the last stop and misery just sat back down. “He tell me I ever play it, I’m goin’ lose everythin’. That song’s curled up in the back of my head like a snake, all the time. Even when I’m up there playin’ and singin’, that song’s what I’m thinkin’ of. Everythin’ else just sounds like shit.”

Tears come out his eyes then and he started tremblin’ all over.

“I can’t never be happy, Harp!” he wailed. “I can’t find no peace! I just wants to die! Don’t nothin’ mean nothin’ for me no more!”

I took the .44 out the glove box that night and kept it with me from then on.

***

Next day, I took him to play at Sink City on Route 49 between Drew and Jaquith. We stopped at a drug store in Dwiggins and I bought me a pair of clay earplugs. Don’t know what made me do it.

Sink City was one of them deep country jukes, not much more than a shack, tin roof, spray painted sign, and grass for parkin’. It was situated in a field so’s the farmers could walk to it and ventilate after a long week. They wasn’t nothin’ around. In them last days, seemed like Yeller would pick the most backwoods place he could find, like he didn’t want nobody to hear him. Word traveled fast, and they didn’t meet him there, they beat him there. The field was full of cars, and seemed like the sides of the juke was swellin’ from all the folks packed inside.

The place had blue walls, I ‘member, painted with big tittied black mermaids, squids, and starfish. The ceilin’ was hung with Christmas lights, and it sagged real bad.

They was a smell of fryin’ catfish from the kitchen, and an old rawboned woman dished out greasy sandwiches till Yeller got to the stage. Ever’body slapped his back and whistled him up. He was a million miles from Silvio’s.

He sat down on the little stool and commenced to playin’ without a word, let the piano man and the drummer catch up. He played t

he old songs till people got to yellin’ for some of his own. Then he did that song I’d heard him do at Silvio’s, Damn Fool Woman, but some drunk fool yelled for Cut Through You Sleepin’ through most of it, and Yeller finally went into it. That got the place really sweatin’ and beatin’ on the tables.

They was somethin’ ‘bout them songs that got under your skin. They made the mens holler and the womens shake, got the couples slow draggin’ till they was fit to do the deed right there on the floor. I dunno what it was. I done said already how a fight always broke out.

When he’d played ‘em all, they hollered for more.

Yeller sat there listenin’ to them, his face just as dead as could be. I dunno what he was thinkin’. Then his eyes found mine in the crowd and he nodded at me and said into the mic, “Y’all wanna hear somethin’ you ain’t never heard before?”

The crowd hooted and shouted that they did.

I got a cold sweat and I shoved them clay plugs in my ears just as far as they would go.

The last thing I heard him say was, “This hear’s The Crawlin’ Chaos Blues.”

It was the tune he told me ‘bout, I knew. Maybe it was the one I heard the shadow man playin’ when he led Yeller out into the cotton field. Whatever it was, the people stopped still as Catholics when he started. I know they was words, ‘cause I seent his mouth movin’. He didn’t look out at ‘em whilst he sang, just stared at the floor. His fingers was a blur on the National and I could feel them deep chords in my chest, see his foot stompin’.

Then all hell broke loose.

The people on the floor commenced to dancin’, but wasn’t nothin’ held back. The mens tore they womens’ dresses to the skin, and the womens did the same to the mens’. Folks at the tables fell on each other in the same way. I had to push a big old girl offa me and shove my way to the front door. Time I got there, my shirt was rags. People was rollin’ on the floor and on the bar top like honeymooners. It was crazy.

I seent women clawin’ at the shoulders and backs of they mens, ploughin’ red lines all in they flesh with they fingernails. I heard a couple of loud pops then, made me jump near out my skin, and then I seent what they was. A woman took a pistol out her man’s waistband, even as he was givin’ her the business. She put the barrel in between his teeth and blew the back of his head wide open. I seent the blood splash all over her chest. He was dead, but his body kept movin’ between her legs like a prayin’ mantis. She put the gun up under her own chin then and drove her brains up on the ceilin’. Nobody took no notice.

They was busy doin’ they own things. Things I can’t hardly think on. If hell ever been on earth, if anybody ever laid eyes on pure, unnatural sin, it was there and it was me. I seent a man stranglin’ his woman whilst she tore his eyebrow off with her teeth. They was both of ‘em grinnin’ and laughin’. The owner held the old woman’s head down in the bubblin’ fryer grease whilst he hiked up her skirt, his eyes buggin’ out of his head and mad dog foam runnin’ all down his chin. His throat was cut and they was a bloody razor in the old woman’s hand. Another man charged at the bar like a bull, rammed his head into it, got back up, did it again. Blood was drippin’ down his nose. A gal near me tore her own hair out in clumps.

They was blood ever’where. The whole crowd was rippin’ and tearin’ into each other, limbs twistin’, heads flung back, wailin’ and grinnin’, teeth bloody. I seent a beatin’ heart go floppin’ across the stage, leavin’ spots of blood behind where it bounced.

Yeller just kept on lookin’ into nothin’ and singin’ that song from hell. The drummer had the piano player against the ivories; he was pushin’ his drumsticks in his eyes. The National was gleamin’ green and gold, and for a minute I swear I seent the shadow man’s snaky octopus arms curlin’ ‘round Yeller’s body, ‘round his neck and his ankles, drankin’ him in, drankin’ all of it in, like the sawdust on the floor was drankin’ up the blood. I seent the grinnin’ shadow man hisself risin’ up behind him, them Pharaoh eyes lookin’ across all that tearin’ flesh right into my soul.

I threw open the door to run, but they wasn’t nowhere to go. Instead of the field of cars and old Route 49, I swear they was nothin’ out there – nothin’ but a swirlin’ tornado blackness. If I’d a stepped outside, I felt I would’ve fallen forever.

I had the .44 and I pulled it. I don’t know for sure if I aimed for him or not, but I didn’t stop squeezin’ that trigger. I seent men and women go down from my bullets. They blowed a path to the stage, and when I had shot six, Yeller was lyin’ on his back with the National across his chest and the shadow man was gone. The liquor caught fire behind the bar, I don’t know how. But the way that little juke was built I knew it was goin’ up. When I looked back outside, the field and the cars was there again, so I run.

I found the Catalina and I got inside and got it movin’. I smashed into parked cars left and right tearin’ outta there. I didn’t care. Some people come runnin’ out, some of ‘em on fire. I seent ‘em in my mirrors, but I was like Lot. I didn’t stop till I left that dirt road behind and hit 49.

I drove till that burnin’ juke wasn’t nothin’ but a speck of starlight in the Mississippi black behind me. Then I couldn’t see it no more.

The highway patrol caught me doin’ ninety-five through Clarksdale, and finally knocked me offa DeSoto Ave, sent the Catalina rollin’ into a ditch. It was the only way they could’ve got me to stop. I couldn’t even hear the sirens with the earplugs. I was laughin’ when they pulled me out.

When I got out the hospital, I stood trial, but didn’t nobody bring up Sink City. On account of I had hauled ass through a white part of town and wrecked a couple of old money cars, I got the choice of goin’ to the pen or Vietnam. Three years later, I lost my leg to a different kinda Mister Charlie at Dak To.

I get to thinkin’ how things played out, and I think on Yeller and Uncle Luke, and even Robert Johnson, how they all made the deal and how they all was murdered short of gettin’ big. I wonder ‘bout how folks is moved and played like checkers by powers maybe we ain’t s’posed to see, and I wonder if Daddy and I maybe played the same part. Maybe Uncle Luke didn’t get his throat cut over no woman and maybe it wasn’t no accident I brang the .44 and them earplugs into the Sink City that night.

Even now, when I got the choice between dwellin’ on the jungle and that little Delta juke joint in the night, I chooses the ‘Nam every time.

Every time.

The Nyarlathotep Event

by Jonathan Wood (2011)

Case File #1:Performance

The Oxford Playhouse. Now.

For the record, it is very difficult to pinpoint the exact moment when you went wrong if a woman with a Laura Ashley dress and blood-stained teeth is rhythmically beating your head against the floor. Just so you know.

Ten minutes before

Here’s a treat: a night out at the theater courtesy of work. All expenses paid. The only catch—I might have to gun down the performer halfway through.

See this is the problem with working for shadowy government agencies. There’s always rough to go with the smooth. Yes, you get to enjoy an evening of ancient Egyptian magics, but it is being performed by an interdimensional avatar called Nyarlathotep who hales from a dimension representing humanity’s collective fears. Silver lining meet cloud.

Still, just another night out for Agent Arthur Wallace of MI37.

The niggling familiarity of the the name Nyarlathotep clears up as soon as he steps out on stage. Lovecraft. Whoever summoned him, named him after a gibbering literary horror.

Which, I feel, should inform my plan. Except the only plan I seem to remember old Lovecraft providing was running howling into the night, so I’m not sure how helpful that’s going to be.

Nyarlathotep stands seven feet tall, wrapped in blood red rags. They hang from his shoulders like a cloak. They wreathe his face. Red mist billows about his feet, spills into the theater, spreads out over feet and ankles. People in the front row let out odd b

arking sounds—the terrifying inbred cousin of laughter. And I’m pretty sure Nyarlathotep’s not told any jokes yet.

And screw evaluating the situation. I reach for my gun.

Nyarlathotep opens his mouth.

There are no words. His mouth moves. Sounds emerge. But it is something beyond speech. Something more profound. Some kinesthetic reflex of bile and horror.

The buzzing of flies. The stench of rotting meat filling my nose my mouth. Burning my throat. I gag. Heave up bile. A liquid scream. Pins in my arms. Needles, and nails, and shards of glass. The grind of cigarette against skin. My brain is burning, melting, is fecal matter sloshing in my skull.

And still his mouth stretches behind reams of cloth. And on and on pours out the filth. Into me.

My gun. I need-

I grab for the thing with numb fingers. Atrocities flicker at the edges of my vision. A noise like a kettle boiling rising, rising, up, and up like an itch I need to reach into my brain to scratch.

Somehow I get the gun loose. I half see it out of one eye, through filters of horror and peeling flesh. I try to sight Nyarlathotep, but I might as well be trying to shoot the moon.

Screw it. I pull the trigger.

The muzzle’s thunderclap hits me like water to the face. Abruptly I’m just a man on his back in a theater, waving a gun about, while around me everyone goes insane.

Men and women are on all fours. They roll in fights. Some screw. Some scream.

On stage, Nyarlathotep stands, arms wide, welcoming it all. The conductor of this pageant of madness. And, Lovecraft old buddy, running and screaming does seem like a good idea right about now.

On the other hand, that’s not what I get paid to do. So I stand. I steady my gun. I draw a bead on the bastard. I think about how I should probably change careers.

Which is exactly the moment the woman in the Laura Ashley number clotheslines me around my throat and brings me down.

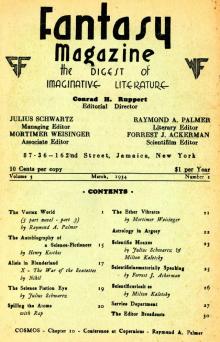

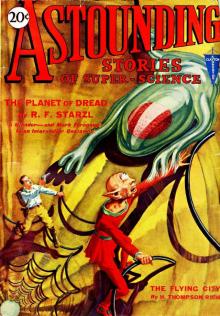

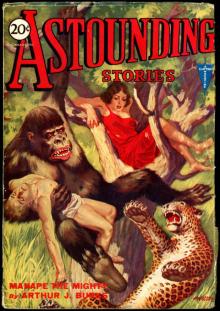

Astounding Stories, March, 1931

Astounding Stories, March, 1931 Astounding Stories, February, 1931

Astounding Stories, February, 1931 Futuria Fantasia, Spring 1940

Futuria Fantasia, Spring 1940 The King's Daughter and Other Stories for Girls

The King's Daughter and Other Stories for Girls Uncanny Tales

Uncanny Tales Masters of Noir: Volume Two

Masters of Noir: Volume Two Witty Pieces by Witty People

Witty Pieces by Witty People Sylvaneth

Sylvaneth Space Wolves

Space Wolves Hammerhal & Other Stories

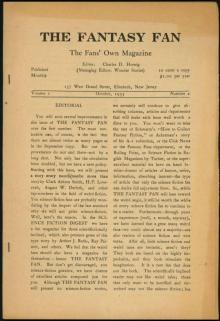

Hammerhal & Other Stories The Fantasy Fan, March, 1934

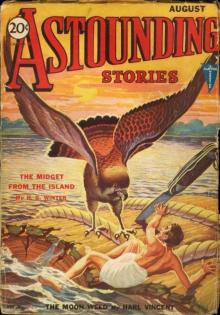

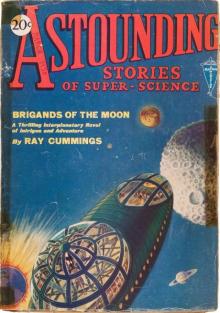

The Fantasy Fan, March, 1934 Astounding Stories of Super-Science, August 1930

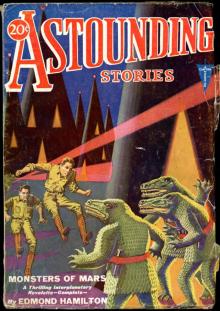

Astounding Stories of Super-Science, August 1930 Astounding Stories, August, 1931

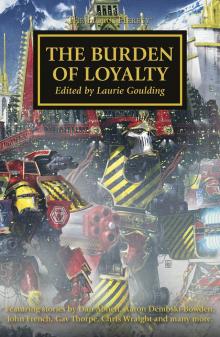

Astounding Stories, August, 1931 The Burden of Loyalty

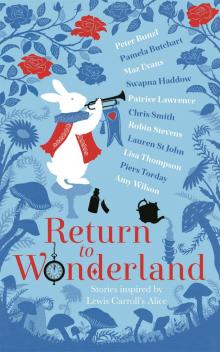

The Burden of Loyalty Return to Wonderland

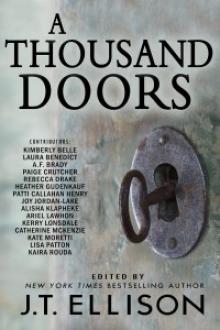

Return to Wonderland Anthology - A Thousand Doors

Anthology - A Thousand Doors The Fantasy Fan, October 1933

The Fantasy Fan, October 1933 Astounding Stories, June, 1931

Astounding Stories, June, 1931 Southern Stories

Southern Stories Astounding Stories of Super-Science, May, 1930

Astounding Stories of Super-Science, May, 1930 The Fantasy Fan December 1933

The Fantasy Fan December 1933 Adventures in Many Lands

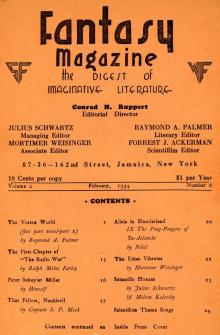

Adventures in Many Lands The Fantasy Fan February 1934

The Fantasy Fan February 1934 The Fantasy Fan November 1933

The Fantasy Fan November 1933 Astounding Stories, April, 1931

Astounding Stories, April, 1931 Fame and Fortune Weekly, No. 801, February 4, 1921

Fame and Fortune Weekly, No. 801, February 4, 1921 Astounding Stories of Super-Science, November, 1930

Astounding Stories of Super-Science, November, 1930 Astounding Stories of Super-Science January 1931

Astounding Stories of Super-Science January 1931 A Monk of Fife

A Monk of Fife Astounding Stories of Super-Science September 1930

Astounding Stories of Super-Science September 1930 Astounding Stories of Super-Science July 1930

Astounding Stories of Super-Science July 1930 Astounding Stories of Super-Science, June, 1930

Astounding Stories of Super-Science, June, 1930 Astounding Stories of Super-Science, October, 1930

Astounding Stories of Super-Science, October, 1930 Astounding Stories of Super-Science, March 1930

Astounding Stories of Super-Science, March 1930 The Fantasy Fan January 1934

The Fantasy Fan January 1934 The Fantasy Fan September 1933

The Fantasy Fan September 1933 Astounding Stories of Super-Science February 1930

Astounding Stories of Super-Science February 1930 Astounding Stories, May, 1931

Astounding Stories, May, 1931 Strange Stories of Colonial Days

Strange Stories of Colonial Days Golden Age of Science Fiction Vol IX

Golden Age of Science Fiction Vol IX Astounding Stories of Super-Science, December 1930

Astounding Stories of Super-Science, December 1930 Evolutions: Essential Tales of the Halo Universe

Evolutions: Essential Tales of the Halo Universe Good Stories Reprinted from the Ladies' Home Journal of Philadelphia

Good Stories Reprinted from the Ladies' Home Journal of Philadelphia Dragons!

Dragons! Murder Takes a Holiday

Murder Takes a Holiday Legacies of Betrayal

Legacies of Betrayal STAR WARS: TALES FROM THE CLONE WARS

STAR WARS: TALES FROM THE CLONE WARS Strange New Worlds 2016

Strange New Worlds 2016 Lippincott's Magazine, August, 1885

Lippincott's Magazine, August, 1885 Golden Age of Science Fiction Vol X

Golden Age of Science Fiction Vol X Hot Stuff

Hot Stuff Santa Wore Spurs

Santa Wore Spurs Paranormal Erotica

Paranormal Erotica Tangled Hearts: A Menage Collection

Tangled Hearts: A Menage Collection Sweet Tea and Jesus Shoes

Sweet Tea and Jesus Shoes The Journey Prize Stories 25

The Journey Prize Stories 25 Wild Western Tales 2: 101 Classic Western Stories Vol. 2 (Civitas Library Classics)

Wild Western Tales 2: 101 Classic Western Stories Vol. 2 (Civitas Library Classics) (5/15) The Golden Age of Science Fiction Volume V: An Anthology of 50 Short Stories

(5/15) The Golden Age of Science Fiction Volume V: An Anthology of 50 Short Stories (4/15) The Golden Age of Science Fiction Volume IV: An Anthology of 50 Short Stories

(4/15) The Golden Age of Science Fiction Volume IV: An Anthology of 50 Short Stories Ten Journeys

Ten Journeys The Boss

The Boss The Penguin Book of French Poetry

The Penguin Book of French Poetry Golden Age of Science Fiction Vol VIII

Golden Age of Science Fiction Vol VIII His Cinderella Housekeeper 3-in-1

His Cinderella Housekeeper 3-in-1 The Magazine of Fantasy & Science Fiction - July/August 2016

The Magazine of Fantasy & Science Fiction - July/August 2016 PYRATE CTHULHU - Tales of the Cthulhu Mythos (vol.2)

PYRATE CTHULHU - Tales of the Cthulhu Mythos (vol.2) Tales from a Master's Notebook

Tales from a Master's Notebook April 1930

April 1930 New Erotica 6

New Erotica 6 Damocles

Damocles The Longest Night Vol. 1

The Longest Night Vol. 1 The Golden Age of Science Fiction Volume VI: An Anthology of 50 Short Stories

The Golden Age of Science Fiction Volume VI: An Anthology of 50 Short Stories (1/15) The Golden Age of Science Fiction: An Anthology of 50 Short Stories

(1/15) The Golden Age of Science Fiction: An Anthology of 50 Short Stories Eye of Terra

Eye of Terra ONCE UPON A REGENCY CHRISTMAS

ONCE UPON A REGENCY CHRISTMAS Nexus Confessions

Nexus Confessions Passionate Kisses

Passionate Kisses War Without End

War Without End Doctor Who: Time Lord Fairy Tales

Doctor Who: Time Lord Fairy Tales Gotrek and Felix: The Anthology

Gotrek and Felix: The Anthology WESTERN CHRISTMAS PROPOSALS

WESTERN CHRISTMAS PROPOSALS The Journey Prize Stories 27

The Journey Prize Stories 27 The Silent War

The Silent War Liaisons

Liaisons Ellora's Cavemen: Tales from the Temple IV

Ellora's Cavemen: Tales from the Temple IV Ellora's Cavemen: Tales from the Temple II

Ellora's Cavemen: Tales from the Temple II Some of the Best From Tor.com, 2013 Edition: A Tor.Com Original

Some of the Best From Tor.com, 2013 Edition: A Tor.Com Original Urban Occult

Urban Occult Fractures

Fractures The Stories: Five Years of Original Fiction on Tor.com

The Stories: Five Years of Original Fiction on Tor.com The Penguin Book of Modern British Short Stories

The Penguin Book of Modern British Short Stories Mortarch of Night

Mortarch of Night The Portable Nineteenth-Century African American Women Writers

The Portable Nineteenth-Century African American Women Writers The Golden Age of Science Fiction Volume VII: An Anthology of 50 Short Stories

The Golden Age of Science Fiction Volume VII: An Anthology of 50 Short Stories Holy Bible: King James Version, The

Holy Bible: King James Version, The Eight Rooms

Eight Rooms sanguineangels

sanguineangels DarkNightsWithaBillionaireBundle

DarkNightsWithaBillionaireBundle Casserole Diplomacy and Other Stories

Casserole Diplomacy and Other Stories How I Survived My Summer Vacation

How I Survived My Summer Vacation Alfred Hitchcock Presents: 16 Skeletons From My Closet

Alfred Hitchcock Presents: 16 Skeletons From My Closet Lords, Ladies, Butlers and Maids

Lords, Ladies, Butlers and Maids The B4 Leg

The B4 Leg Ellora's Cavemen: Tales from the Temple I

Ellora's Cavemen: Tales from the Temple I 2014 Campbellian Anthology

2014 Campbellian Anthology There Is Only War

There Is Only War Obsidian Alliances

Obsidian Alliances 12 Gifts for Christmas

12 Gifts for Christmas Scary Holiday Tales to Make You Scream

Scary Holiday Tales to Make You Scream 25 For 25

25 For 25 The Plagues of Orath

The Plagues of Orath And Then He Kissed Me

And Then He Kissed Me Star Trek - Gateways 7 - WHAT LAY BEYOND

Star Trek - Gateways 7 - WHAT LAY BEYOND Laugh Your Head Off Again and Again

Laugh Your Head Off Again and Again The Balfour Legacy

The Balfour Legacy Golden Age of Science Fiction Vol XI

Golden Age of Science Fiction Vol XI (3/15) The Golden Age of Science Fiction Volume III: An Anthology of 50 Short Stories

(3/15) The Golden Age of Science Fiction Volume III: An Anthology of 50 Short Stories Shas'o

Shas'o Astounding Science Fiction Stories: An Anthology of 350 Scifi Stories Volume 2 (Halcyon Classics)

Astounding Science Fiction Stories: An Anthology of 350 Scifi Stories Volume 2 (Halcyon Classics) Twists in Time

Twists in Time Meduson

Meduson The Magazine of Fantasy & Science Fiction - August 1980

The Magazine of Fantasy & Science Fiction - August 1980 The Journey Prize Stories 22

The Journey Prize Stories 22 The Book that Made Me

The Book that Made Me Angels of Death Anthology

Angels of Death Anthology Ask the Bones

Ask the Bones Emergence

Emergence Beware the Little White Rabbit

Beware the Little White Rabbit Xcite Delights Book 1

Xcite Delights Book 1 Where flap the tatters of the King

Where flap the tatters of the King The Journey Prize Stories 21

The Journey Prize Stories 21 Tales of the Slayer, Volume II

Tales of the Slayer, Volume II Glass Empires

Glass Empires Golden Age of Science Fiction Vol XII

Golden Age of Science Fiction Vol XII (2/15) The Golden Age of Science Fiction Volume II: An Anthology of 50 Short Stories

(2/15) The Golden Age of Science Fiction Volume II: An Anthology of 50 Short Stories Fairytale Collection

Fairytale Collection Angels!

Angels! Golden Age of Science Fiction Vol XIII

Golden Age of Science Fiction Vol XIII