Golden Age of Science Fiction Vol IX Read online

Page 30

"I used to be a short order cook when I was finishing school," I told her. But she'd ruined the line. The grateful look and laugh from Jenny weren't needed now. And curiously, I felt grateful to Eve for it. I got up and went after Napier.

I found him in Bullard's little cubbyhole of a cabin. He must have chased Grundy off, and now he was just drawing a hypo out of the cook's arm. "It'll take the pain away," he was saying softly. "And I'll see that he doesn't hit you again. You'll be all right, now. And in the morning, I'll come and listen to you. Just go to sleep. Maybe she'll come back and tell you more."

He must have heard me, since he signalled me out with his hand, and backed out quietly himself, still talking. He shut the door, and clicked the lock.

Bullard heard it, though. He jerked to a sitting position, and screamed. "No! No! He'll kill me! I'm a good man...."

He hunched up on the bed, forcing the sheet into his mouth. When he looked up a second later, his face was frozen in fear, but it was a desperate, calm kind of fear. He turned to face us, and his voice raised to a full shout, with every word as clear as he could make it.

"All right. Now I'll never tell you the secret. Now you can all die without air. I promise I'll never tell you what I know!"

He fell back, beating at the sheet with his hand and sobbing hysterically. Napier watched him. "Poor devil," the doctor said at last. "Well, in another minute the shot will take effect. Maybe he's lucky. He won't be worrying for awhile. And maybe he'll be rational tomorrow."

"All the same, I'm going to stand guard until Muller gets someone else here," I decided. I kept remembering Lomax.

Napier nodded, and half an hour later Bill Sanderson came to take over the watch. Bullard was sleeping soundly.

The next day, though, he woke up to start moaning and writhing again. But he was keeping his word. He refused to answer any questions. Napier looked worried as he reported he'd given the cook another shot of sedative. There was nothing else he could do.

Cooking was a relief, in a way. By the time Eve and I had scrubbed all the pots into what she considered proper order, located some of the food lockers, and prepared and served a couple of meals, we'd evolved a smooth system that settled into a routine with just enough work to help keep our minds off the dwindling air in the tanks. In anything like a kitchen, she lost most of her mannish pose and turned into a live, efficient woman. And she could cook.

"First thing I learned," she told me. "I grew up in a kitchen. I guess I'd never have turned to photography if my kid brother hadn't been using our sink for his darkroom."

Wilcox brought her a bottle of his wine to celebrate her first dinner. He seemed to want to stick around, but she chased him off after the first drink. We saved half the bottle to make a sauce the next day.

It never got made. Muller called a council of war, and his face was pinched and old. He was leaning on Jenny as Eve and I came into the mess hall; oddly, she seemed to be trying to buck him up. He got down to the facts as soon as all of us were together.

"Our oxygen tanks are empty," he announced. "They shouldn't be--but they are. Someone must have sabotaged them before the plants were poisoned--and done it so the dials don't show it. I just found it out when the automatic switch to a new tank failed to work. We now have the air in the ship, and no more. Dr. Napier and I have figured that this will keep us all alive with the help of the plants for no more than fifteen days. I am open to any suggestions!"

* * * * *

There was silence after that, while it soaked in. Then it was broken by a thin scream from Phil Riggs. He slumped into a seat and buried his head in his hands. Pietro put a hand on the man's thin shoulders, "Captain Muller--"

"Kill 'em!" It was Grundy's voice, bellowing sharply. "Let'em breathe space! They got us into it! We can make out with the plants left! It's our ship!"

Muller had walked forward. Now his fist lashed out, and Grundy crumpled. He lay still for a second, then got to his feet unsteadily. Jenny screamed, but Muller moved steadily back to his former place without looking at the mate. Grundy hesitated, fumbled in his pocket for something, and swallowed it.

"Captain, sir!" His voice was lower this time.

"Yes, Mr. Grundy?"

"How many of us can live off the plants?"

"Ten--perhaps eleven."

"Then--then give us a lottery!"

Pietro managed to break in over the yells of the rest of the crew. "I was about to suggest calling for volunteers, Captain Muller. I still have enough faith in humanity to believe...."

"You're a fool, Dr. Pietro," Muller said flatly. "Do you think Grundy would volunteer? Or Bullard? But thanks for clearing the air, and admitting your group has nothing more to offer. A lottery seems to be the only fair system."

He sat down heavily. "We have tradition on this; in an emergency such as this, death lotteries have been held, and have been considered legal afterwards. Are there any protests?"

I could feel my tongue thicken in my mouth. I could see the others stare about, hoping someone would object, wondering if this could be happening. But nobody answered, and Muller nodded reluctantly. "A working force must be left. Some men are indispensable. We must have an engineer, a navigator, and a doctor. One man skilled with engine-room practice and one with deck work must remain."

"And the cook goes," Grundy yelled. His eyes were intent and slitted again.

Some of both groups nodded, but Muller brought his fist down on the table. "This will be a legal lottery, Mr. Grundy. Dr. Napier will draw for him."

"And for myself," Napier said. "It's obvious that ten men aren't going on to Saturn--you'll have to turn back, or head for Jupiter. Jupiter, in fact, is the only sensible answer. And a ship can get along without a doctor that long when it has to. I demand my right to the draw."

Muller only shrugged and laid down the rules. They were simple enough. He would cut drinking straws to various lengths, and each would draw one. The two deck hands would compare theirs, and the longer would be automatically safe. The same for the pair from the engine-room. Wilcox was safe. "Mr. Peters and I will also have one of us eliminated," he added quietly. "In an emergency, our abilities are sufficiently alike."

The remaining group would have their straws measured, and the seven shortest ones would be chosen to remove themselves into a vacant section between hulls without air within three hours, or be forcibly placed there. The remaining ten would head for Jupiter if no miracle removed the danger in those three hours.

Peters got the straws, and Muller cut them and shuffled them. There was a sick silence that let us hear the sounds of the scissors with each snip. Muller arranged them so the visible ends were even. "Ladies first," he said. There was no expression on his face or in his voice.

Jenny didn't giggle, but neither did she balk. She picked a straw, and then shrieked faintly. It was obviously a long one. Eve reached for hers--

And Wilcox yelled suddenly. "Captain Muller, protest! Protest! You're using all long straws for the women!" He had jumped forward, and now struck down Muller's hand, proving his point.

"You're quite right, Mr. Wilcox," Muller said woodenly. He dropped his hand toward his lap and came up with a group of the straws that had been cut, placed there somehow without our seeing it. He'd done a smooth job of it, but not smooth enough. "I felt some of you would notice it, but I also felt that gentlemen would prefer to see ladies given the usual courtesies."

He reshuffled the assorted straws, and then paused. "Mr. Tremaine, there was a luxury liner named the Lauri Ellu with an assistant engineer by your name; and I believe you've shown a surprising familiarity with certain customs of space. A few days ago, Jenny mentioned something that jogged my memory. Can you still perform the duties of an engineer?"

Wilcox had started to protest at the delay. Now shock ran through him. He stared unbelievingly from Muller to me and back, while his face blanched. I could guess what it must have felt like to see certain safety cut to a 50 per cent chance, and I didn't like the way M

uller was willing to forget until he wanted to take a crack at Wilcox for punishment. But....

"I can," I answered. And then, because I was sick inside myself for cutting under Wilcox, I managed to add, "But I--I waive my chance at immunity!"

"Not accepted," Muller decided. "Jenny, will you draw?"

It was pretty horrible. It was worse when the pairs compared straws. The animal feelings were out in the open then. Finally, Muller, Wilcox, and two crewmen dropped out. The rest of us went up to measure our straws.

It took no more than a minute. I stood staring down at the ruler, trying to stretch the tiny thing I'd drawn. I could smell the sweat rising from my body. But I knew the answer. I had three hours left!

* * * * *

"Riggs, Oliver, Nolan, Harris, Tremaine, Napier and Grundy," Muller announced.

A yell came from Grundy. He stood up, with the engine man named Oliver, and there was a gun in his hand. "No damned big brain's kicking me off my ship," he yelled. "You guys know me. Hey, roooob!"

Oliver was with him, and the other three of the crew sprang into the group. I saw Muller duck a shot from Grundy's gun, and leap out of the room. Then I was in it, heading for Grundy. Beside me, Peters was trying to get a chair broken into pieces. I felt something hit my shoulder, and the shock knocked me downward, just as a shot whistled over my head.

Gravity cut off!

Someone bounced off me. I got a piece of the chair that floated by, found the end cracked and sharp, and tried to spin towards Grundy, but I couldn't see him. I heard Eve's voice yell over the other shouts. I spotted the plate coming for me, but I was still in midair. It came on steadily, edge on, and I felt it break against my forehead. Then I blacked out.

V

I had the grandaddy of all headaches when I came to. Doc Napier's face was over me, and Jenny and Muller were working on Bill Sanderson. There was a surprisingly small and painful lump on my head. Pietro and Napier helped me up, and I found I could stand after a minute.

There were four bodies covered with sheets on the floor. "Grundy, Phil Riggs, Peters and a deckhand named Storm," Napier said. "Muller gave us a whiff of gas and not quite in time."

"Is the time up?" I asked. It was the only thing I could think of.

Pietro shook his head sickly. "Lottery is off. Muller says we'll have to hold another, since Storm and Peters were supposed to be safe. But not until tomorrow."

Eve came in then, lugging coffee. Her eyes found me, and she managed a brief smile. "I gave the others coffee," she reported to Muller. "They're pretty subdued now."

"Mutiny!" Muller helped Jenny's brother to his feet and began helping him toward the door. "Mutiny! And I have to swallow that!"

Pietro watched him go, and handed Eve back his cup. "And there's no way of knowing who was on which side. Dr. Napier, could you do something...."

He held out his hands that were shaking, and Napier nodded. "I can use a sedative myself. Come on back with me."

Eve and I wandered back to the kitchen. I was just getting my senses back. The damned stupidity of it all. And now it would have to be done over. Three of us still had to have our lives snuffed out so the others could live--and we all had to go through hell again to find out which.

Eve must have been thinking the same. She sank down on a little stool, and her hand came out to find mine. "For what? Paul, whoever poisoned the plants knew it would go this far! He had to! What's to be gained? Particularly when he'd have to go through all this, too! He must have been crazy!"

"Bullard couldn't have done it," I said slowly.

"Why should it be Bullard? How do we know he was insane? Maybe when he was shouting that he wouldn't tell, he was trying to make a bribe to save his own life. Maybe he's as scared as we are. Maybe he was making sense all along, if we'd only listened to him. He--"

She stood up and started back toward the lockers, but I caught her hand. "Eve, he wouldn't have done it--the killer--if he'd had to go through the lottery! He knew he was safe! That's the one thing we've been overlooking. The man to suspect is the only man who could be sure he would get back! My God, we saw him juggle those straws to save Jenny! He knew he'd control the lottery."

She frowned. "But ... Paul, he practically suggested the lottery! Grundy brought it up, but he was all ready for it." The frown vanished, then returned. "But I still can't believe it."

"He's the one who wanted to go back all the time. He kept insisting on it, but he had to get back without violating his contract." I grabbed her hand and started toward the nose of the ship, justifying it to her as I went. "The only man with a known motive for returning, the only one completely safe--and we didn't even think of it!"

She was still frowning, but I wasn't wasting time. We came up the corridor to the control room. Ahead the door was slightly open, and I could hear a mutter of Jenny's voice. Then there was the tired rumble of Muller.

"I'll find a way, baby. I don't care how close they watch, we'll make it work. Pick the straw with the crimp in the end--I can do that, even if I can't push one out further again. I tell you, nothing's going to happen to you."

"But Bill--" she began.

I hit the door, slamming it open. Muller sat on a narrow couch with Jenny on his lap. I took off for him, not wasting a good chance when he was handicapped. But I hadn't counted on Jenny. She was up, and her head banged into my stomach before I knew she was coming. I felt the wind knocked out, but I got her out of my way--to look up into the muzzle of a gun in Muller's hands.

"You'll explain this, Mr. Tremaine," he said coldly. "In ten seconds, I'll have an explanation or a corpse."

"Go ahead," I told him. "Shoot, damn you! You'll get away with this, too, I suppose. Mutiny, or something. And down in that rotten soul of yours, I suppose you'll be gloating at how you made fools of us. The only man on board who was safe even from a lottery, and we couldn't see it. Jenny, I hope you'll be happy with this butcher. Very happy!"

He never blinked. "Say that about the only safe man aboard again," he suggested.

I repeated it, with details. But he didn't like my account. He turned to Eve, and motioned for her to take it up. She was frowning harder, and her voice was uncertain, but she summed up our reasons quickly enough.

And suddenly Muller was on his feet. "Mr. Tremaine, for a damned idiot, you have a good brain. You found the key to the problem, even if you couldn't find the lock. Do you know what happens to a captain who permits a death lottery, even what I called a legal one? He doesn't captain a liner--he shoots himself after he delivers his ship, if he's wise! Come on, we'll find the one indispensable man. You stay here, Jenny--you too, Eve!"

Jenny whimpered, but stayed. Eve followed, and he made no comment. And then it hit me. The man who had thought he was indispensable, and hence safe--the man I'd naturally known in the back of my head could be replaced, though no one else had known it until a little while ago.

"He must have been sick when you ran me in as a ringer," I said, as we walked down toward the engine hatch. "But why?"

"I've just had a wild guess as to part of it," Muller said.

* * * * *

Wilcox was listening to the Buxtehude when we shoved the door of his room open, and he had his head back and eyes closed. He snapped to attention, and reached out with one hand toward a drawer beside him. Then he dropped his arm and stood up, to cut off the tape player.

"Mr. Wilcox," Muller said quietly, holding the gun firmly on the engineer. "Mr. Wilcox, I've detected evidence of some of the Venus drugs on your two assistants for some time. It's rather hard to miss the signs in their eyes. I've also known that Mr. Grundy was an addict. I assumed that they were getting it from him naturally. And as long as they performed their duties, I couldn't be choosy on an old ship like this. But for an officer to furnish such drugs--and to smuggle them from Venus for sale to other planets--is something I cannot tolerate. It will make things much simpler if you will surrender those drugs to me. I presume you keep them in those bottles of wine you bring abo

ard?"

Wilcox shook his head slowly, settling back against the tape machine. Then he shrugged and bowed faintly. "The chianti, sir!"

I turned my head toward the bottles, and Eve started forward. Then I yelled as Wilcox shoved his hand down toward the tape machine. The gun came out on a spring as he touched it.

Muller shot once, and the gun missed Wilcox's fingers as the engineer's hand went to his hip, where blood was flowing. He collapsed into the chair behind him, staring at the spot stupidly. "I cut my teeth on tough ships, Mr. Wilcox," Muller said savagely.

The man's face was white, but he nodded slowly, and a weak grin came onto his lips. "Maybe you didn't exaggerate those stories at that," he conceded slowly. "I take it I drew a short straw."

"Very short. It wasn't worth it. No profit from the piddling sale of drugs is worth it."

"There's a group of strings inside the number one fuel locker," Wilcox said between his teeth. The numbness was wearing off, and the shattered bones in his hip were beginning to eat at him. "Paul, pull up one of the packages and bring it here, will you?"

I found it without much trouble--along with a whole row of others, fine cords cemented to the side of the locker. The package I drew up weighed about ten pounds. Wilcox opened it and scooped out a thimbleful of greenish powder. He washed it down with wine.

"Fatal?" Muller asked.

The man nodded. "In that dosage, after a couple of hours. But it cuts out the pain--ah, better already. I won't feel it. Captain, I was never piddling. Your ship has been the sole source of this drug to Mars since a year or so after I first shipped on her. There are about seven hundred pounds of pure stuff out there. Grundy and the others would commit public murder daily rather than lose the few ounces a year I gave them. Imagine what would happen when Pietro conscripted the Wahoo and no drugs arrived. The addicts find out no more is coming--they look for the peddlers--and they start looking for their suppliers...."

He shrugged. "There might have been time and ways, if I could have gotten the ship back to Earth or Jupiter. It might have been recommissioned into the Earth-Mars-Venus run, even. Pietro's injunction caught me before I could transship, but with another chance, I might have gotten the stuff to Mars in time.... Well, it was a chance I took. Satisfied?"

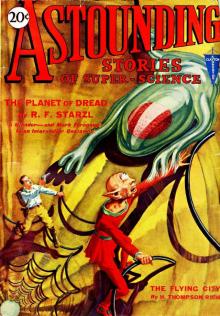

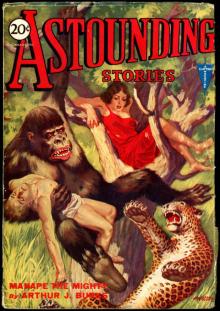

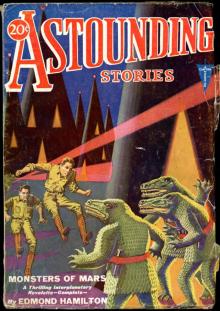

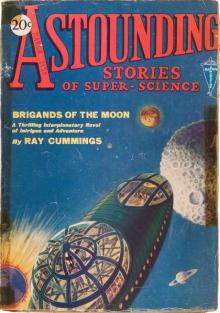

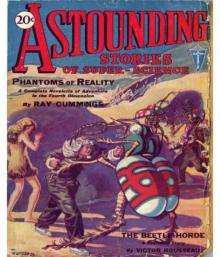

Astounding Stories, March, 1931

Astounding Stories, March, 1931 Astounding Stories, February, 1931

Astounding Stories, February, 1931 Futuria Fantasia, Spring 1940

Futuria Fantasia, Spring 1940 The King's Daughter and Other Stories for Girls

The King's Daughter and Other Stories for Girls Uncanny Tales

Uncanny Tales Masters of Noir: Volume Two

Masters of Noir: Volume Two Witty Pieces by Witty People

Witty Pieces by Witty People Sylvaneth

Sylvaneth Space Wolves

Space Wolves Hammerhal & Other Stories

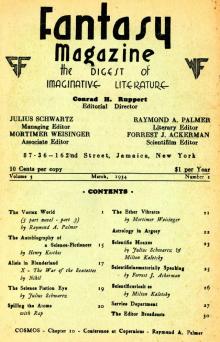

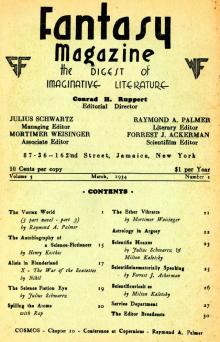

Hammerhal & Other Stories The Fantasy Fan, March, 1934

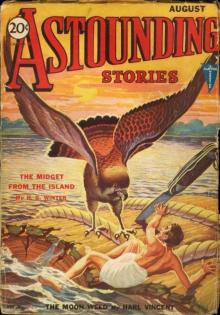

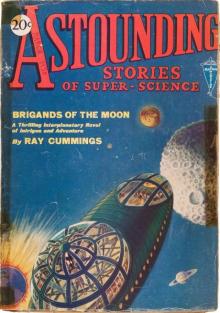

The Fantasy Fan, March, 1934 Astounding Stories of Super-Science, August 1930

Astounding Stories of Super-Science, August 1930 Astounding Stories, August, 1931

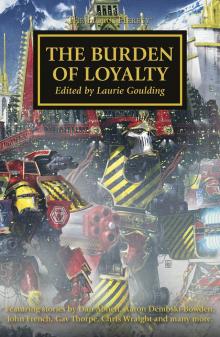

Astounding Stories, August, 1931 The Burden of Loyalty

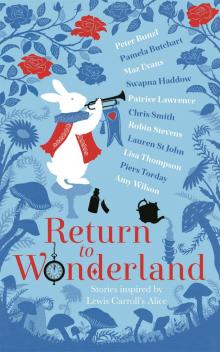

The Burden of Loyalty Return to Wonderland

Return to Wonderland Anthology - A Thousand Doors

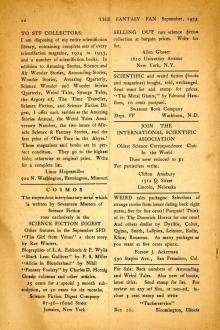

Anthology - A Thousand Doors The Fantasy Fan, October 1933

The Fantasy Fan, October 1933 Astounding Stories, June, 1931

Astounding Stories, June, 1931 Southern Stories

Southern Stories Astounding Stories of Super-Science, May, 1930

Astounding Stories of Super-Science, May, 1930 The Fantasy Fan December 1933

The Fantasy Fan December 1933 Adventures in Many Lands

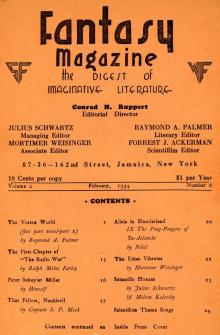

Adventures in Many Lands The Fantasy Fan February 1934

The Fantasy Fan February 1934 The Fantasy Fan November 1933

The Fantasy Fan November 1933 Astounding Stories, April, 1931

Astounding Stories, April, 1931 Fame and Fortune Weekly, No. 801, February 4, 1921

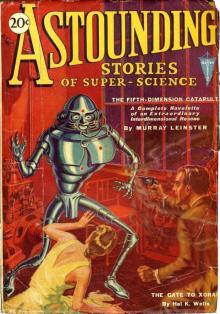

Fame and Fortune Weekly, No. 801, February 4, 1921 Astounding Stories of Super-Science, November, 1930

Astounding Stories of Super-Science, November, 1930 Astounding Stories of Super-Science January 1931

Astounding Stories of Super-Science January 1931 A Monk of Fife

A Monk of Fife Astounding Stories of Super-Science September 1930

Astounding Stories of Super-Science September 1930 Astounding Stories of Super-Science July 1930

Astounding Stories of Super-Science July 1930 Astounding Stories of Super-Science, June, 1930

Astounding Stories of Super-Science, June, 1930 Astounding Stories of Super-Science, October, 1930

Astounding Stories of Super-Science, October, 1930 Astounding Stories of Super-Science, March 1930

Astounding Stories of Super-Science, March 1930 The Fantasy Fan January 1934

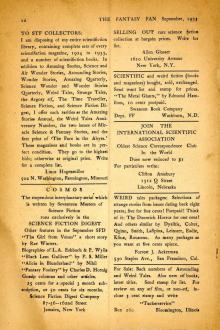

The Fantasy Fan January 1934 The Fantasy Fan September 1933

The Fantasy Fan September 1933 Astounding Stories of Super-Science February 1930

Astounding Stories of Super-Science February 1930 Astounding Stories, May, 1931

Astounding Stories, May, 1931 Strange Stories of Colonial Days

Strange Stories of Colonial Days Golden Age of Science Fiction Vol IX

Golden Age of Science Fiction Vol IX Astounding Stories of Super-Science, December 1930

Astounding Stories of Super-Science, December 1930 Evolutions: Essential Tales of the Halo Universe

Evolutions: Essential Tales of the Halo Universe Good Stories Reprinted from the Ladies' Home Journal of Philadelphia

Good Stories Reprinted from the Ladies' Home Journal of Philadelphia Dragons!

Dragons! Murder Takes a Holiday

Murder Takes a Holiday Legacies of Betrayal

Legacies of Betrayal STAR WARS: TALES FROM THE CLONE WARS

STAR WARS: TALES FROM THE CLONE WARS Strange New Worlds 2016

Strange New Worlds 2016 Lippincott's Magazine, August, 1885

Lippincott's Magazine, August, 1885 Golden Age of Science Fiction Vol X

Golden Age of Science Fiction Vol X Hot Stuff

Hot Stuff Santa Wore Spurs

Santa Wore Spurs Paranormal Erotica

Paranormal Erotica Tangled Hearts: A Menage Collection

Tangled Hearts: A Menage Collection Sweet Tea and Jesus Shoes

Sweet Tea and Jesus Shoes The Journey Prize Stories 25

The Journey Prize Stories 25 Wild Western Tales 2: 101 Classic Western Stories Vol. 2 (Civitas Library Classics)

Wild Western Tales 2: 101 Classic Western Stories Vol. 2 (Civitas Library Classics) (5/15) The Golden Age of Science Fiction Volume V: An Anthology of 50 Short Stories

(5/15) The Golden Age of Science Fiction Volume V: An Anthology of 50 Short Stories (4/15) The Golden Age of Science Fiction Volume IV: An Anthology of 50 Short Stories

(4/15) The Golden Age of Science Fiction Volume IV: An Anthology of 50 Short Stories Ten Journeys

Ten Journeys The Boss

The Boss The Penguin Book of French Poetry

The Penguin Book of French Poetry Golden Age of Science Fiction Vol VIII

Golden Age of Science Fiction Vol VIII His Cinderella Housekeeper 3-in-1

His Cinderella Housekeeper 3-in-1 The Magazine of Fantasy & Science Fiction - July/August 2016

The Magazine of Fantasy & Science Fiction - July/August 2016 PYRATE CTHULHU - Tales of the Cthulhu Mythos (vol.2)

PYRATE CTHULHU - Tales of the Cthulhu Mythos (vol.2) Tales from a Master's Notebook

Tales from a Master's Notebook April 1930

April 1930 New Erotica 6

New Erotica 6 Damocles

Damocles The Longest Night Vol. 1

The Longest Night Vol. 1 The Golden Age of Science Fiction Volume VI: An Anthology of 50 Short Stories

The Golden Age of Science Fiction Volume VI: An Anthology of 50 Short Stories (1/15) The Golden Age of Science Fiction: An Anthology of 50 Short Stories

(1/15) The Golden Age of Science Fiction: An Anthology of 50 Short Stories Eye of Terra

Eye of Terra ONCE UPON A REGENCY CHRISTMAS

ONCE UPON A REGENCY CHRISTMAS Nexus Confessions

Nexus Confessions Passionate Kisses

Passionate Kisses War Without End

War Without End Doctor Who: Time Lord Fairy Tales

Doctor Who: Time Lord Fairy Tales Gotrek and Felix: The Anthology

Gotrek and Felix: The Anthology WESTERN CHRISTMAS PROPOSALS

WESTERN CHRISTMAS PROPOSALS The Journey Prize Stories 27

The Journey Prize Stories 27 The Silent War

The Silent War Liaisons

Liaisons Ellora's Cavemen: Tales from the Temple IV

Ellora's Cavemen: Tales from the Temple IV Ellora's Cavemen: Tales from the Temple II

Ellora's Cavemen: Tales from the Temple II Some of the Best From Tor.com, 2013 Edition: A Tor.Com Original

Some of the Best From Tor.com, 2013 Edition: A Tor.Com Original Urban Occult

Urban Occult Fractures

Fractures The Stories: Five Years of Original Fiction on Tor.com

The Stories: Five Years of Original Fiction on Tor.com The Penguin Book of Modern British Short Stories

The Penguin Book of Modern British Short Stories Mortarch of Night

Mortarch of Night The Portable Nineteenth-Century African American Women Writers

The Portable Nineteenth-Century African American Women Writers The Golden Age of Science Fiction Volume VII: An Anthology of 50 Short Stories

The Golden Age of Science Fiction Volume VII: An Anthology of 50 Short Stories Holy Bible: King James Version, The

Holy Bible: King James Version, The Eight Rooms

Eight Rooms sanguineangels

sanguineangels DarkNightsWithaBillionaireBundle

DarkNightsWithaBillionaireBundle Casserole Diplomacy and Other Stories

Casserole Diplomacy and Other Stories How I Survived My Summer Vacation

How I Survived My Summer Vacation Alfred Hitchcock Presents: 16 Skeletons From My Closet

Alfred Hitchcock Presents: 16 Skeletons From My Closet Lords, Ladies, Butlers and Maids

Lords, Ladies, Butlers and Maids The B4 Leg

The B4 Leg Ellora's Cavemen: Tales from the Temple I

Ellora's Cavemen: Tales from the Temple I 2014 Campbellian Anthology

2014 Campbellian Anthology There Is Only War

There Is Only War Obsidian Alliances

Obsidian Alliances 12 Gifts for Christmas

12 Gifts for Christmas Scary Holiday Tales to Make You Scream

Scary Holiday Tales to Make You Scream 25 For 25

25 For 25 The Plagues of Orath

The Plagues of Orath And Then He Kissed Me

And Then He Kissed Me Star Trek - Gateways 7 - WHAT LAY BEYOND

Star Trek - Gateways 7 - WHAT LAY BEYOND Laugh Your Head Off Again and Again

Laugh Your Head Off Again and Again The Balfour Legacy

The Balfour Legacy Golden Age of Science Fiction Vol XI

Golden Age of Science Fiction Vol XI (3/15) The Golden Age of Science Fiction Volume III: An Anthology of 50 Short Stories

(3/15) The Golden Age of Science Fiction Volume III: An Anthology of 50 Short Stories Shas'o

Shas'o Astounding Science Fiction Stories: An Anthology of 350 Scifi Stories Volume 2 (Halcyon Classics)

Astounding Science Fiction Stories: An Anthology of 350 Scifi Stories Volume 2 (Halcyon Classics) Twists in Time

Twists in Time Meduson

Meduson The Magazine of Fantasy & Science Fiction - August 1980

The Magazine of Fantasy & Science Fiction - August 1980 The Journey Prize Stories 22

The Journey Prize Stories 22 The Book that Made Me

The Book that Made Me Angels of Death Anthology

Angels of Death Anthology Ask the Bones

Ask the Bones Emergence

Emergence Beware the Little White Rabbit

Beware the Little White Rabbit Xcite Delights Book 1

Xcite Delights Book 1 Where flap the tatters of the King

Where flap the tatters of the King The Journey Prize Stories 21

The Journey Prize Stories 21 Tales of the Slayer, Volume II

Tales of the Slayer, Volume II Glass Empires

Glass Empires Golden Age of Science Fiction Vol XII

Golden Age of Science Fiction Vol XII (2/15) The Golden Age of Science Fiction Volume II: An Anthology of 50 Short Stories

(2/15) The Golden Age of Science Fiction Volume II: An Anthology of 50 Short Stories Fairytale Collection

Fairytale Collection Angels!

Angels! Golden Age of Science Fiction Vol XIII

Golden Age of Science Fiction Vol XIII