Laugh Your Head Off Again and Again Read online

Page 4

She went to the bathroom and brushed her teeth, called ‘goodnight’ down the stairs, and changed into her pyjamas.

‘Goodnight, Count Hedgehogula,’ she said as she switched off the bedside lamp.

‘Sweet dreams,’ said the vampire.

The next morning, instead of feeling a sense of doom, Tracey woke up laughing at the strange dream she’d had. A vampire hedgehog! She’d never heard anything so crazy.

But as she was getting dressed she heard a small voice say from under the bed, ‘I want to drink your milk!’

‘You mean you’re real?’ Tracey said, bending down to look under the bed.

A pair of beady eyes blinked back at her.

‘I’m sorry,’ Tracey said, ‘but I won’t be able to help you find your way home till after school.’

‘I want some more of that special milk,’ said the hedgehog. ‘What makes it taste so good?’

‘It’s cereal milk,’ Tracey explained.

She went downstairs and made two bowls of Crispy Crunchy Crackles, then she carried one upstairs and put it under the bed.

It was only as she was walking to school that she remembered she still had to face Halloween with Stanley Blotson. If he wasn’t responsible for putting a vampire hedgehog under her bed, that meant he had some other devious trick planned.

But the morning passed quietly. Once Stanley jumped out from behind a door and yelled ‘Boo!’, but Tracey had seen him hiding in the first place and so she hardly even flinched.

She’d almost forgotten it was Halloween when she put her hand under her desk to get her ruler and something brushed against her fingers.

Tracey flung herself back in her seat. ‘Ms Handel,’ she called, ‘I think there’s something under my desk.’

Ms Handel frowned. ‘I should think there are lots of things under your desk, Tracey,’ she said.

‘I meant something alive,’ Tracey clarified.

‘Oh,’ said Ms Handel, coming over. ‘That’s another story.’

‘I saw something!’ said Stanley, who was standing behind them. ‘Oh no! Here it comes!’

Suddenly, a snake shot out from under the desk!

‘SNAKE!’ yelled Ms Handel.

But out of the corner of her eye, Tracey had seen Stanley jerk his hand as the snake came flying out.

‘That’s just a rubber snake tied to a fishing line,’ she said accusingly.

Ms Handel whirled around. ‘Stanley,’ she scolded. ‘That’s a terrible trick. I want you to stay behind after school and write I will not hide rubber snakes under my classmates’ desks 50 times.’

‘Hmph,’ said Stanley. ‘You’re no fun, Chicken.’

‘Thank you,’ said Tracey.

‘It’s rather hot in here,’ Ms Handel said, fanning herself. She still looked a bit flustered. ‘Class, we’re going out to the oval to play hacky sack.’

After several rounds of hacky sack, which allowed Ms Handel to blow her whistle until she wasn’t flustered any more, the teacher glanced at her watch and said, ‘Tracey, can you fetch the lunch orders, please?’

Tracey went to the canteen and fetched the basket with the lunch orders, carried it back to the classroom and then returned to the oval.

The bell rang just as she got there, so they all trooped back to class.

‘Hey, what happened to my chocolate milk?’ Stanley demanded when he pulled his lunch order from the basket. ‘The carton is empty.’

‘Maybe you already drank it,’ said Ryan.

‘How could I have drunk it? I only just got here. Was it you, Chicken?’

Tracey looked at the milk he was holding. ‘How could I have drunk it?’ she said. ‘The carton hasn’t been opened.’

Stanley stared at it, puzzled. ‘Then how did the milk get out?’

Another mystery of missing milk . . . Was it possible?

‘Are there fang marks in the carton?’ Tracey asked.

‘Fang marks?’ said Stanley. ‘Don’t be stupid, of course there are no . . . oh. Um, there are some f-fang marks.’

There was a slight tremor in his voice, Tracey noticed. Could Stanley Blotson be scared?

‘You know who likes milk, don’t you?’ she said casually. ‘Snakes.’

Stanley turned so pale it looked as if his blood had been drained by a real vampire.

‘Y-y-you mean like a r-r-real s-s-snake?’ Stanley looked around wildly.

‘That’s right,’ said Tracey. ‘There must be a snake in here. You’re not chicken, are you?’

‘SNAKE!’ Stanley yelled. ‘THERE’S A SNAKE IN THE CLASSROOM! SNAKE!’

Everyone stampeded from the room.

Tracey followed them to the door, then closed it behind them.

‘What are you doing in there, Tracey?’ the teacher called from the other side of the door.

‘Don’t worry, Ms Handel. I know how to deal with snakes.’ Turning back to face the room, Tracey called softly, ‘Count Hedgehogula, are you in here?’

There was no reply, and for a few dreadful moments Tracey feared that she had made a terrible mistake. Maybe there really was a snake in here!

Then a voice said, ‘That milk—it was so tasty.’

The vampire hedgehog waddled out from behind the wastepaper bin, chocolate milk dripping from its fangs.

‘What are you doing here?’ said Tracey.

‘I don’t know. I drank the special milk this morning and it made me very sleepy—vampires usually sleep during the day, you know. So I found a cosy place to rest, and when I woke up I was here—and I could smell the most delicious milk. What was it?’

‘Chocolate milk,’ said Tracey. ‘And that cosy place must have been my schoolbag.’

‘And are there more special milks like this at your school?’

‘Sure,’ said Tracey. ‘There’s strawberry, banana . . . lots of different flavours.’

‘I would like to try them all,’ said the hedgehog. ‘But now I am sleepy again.’

‘You can have a sleep in a minute,’ said Tracey, ‘but first I want you to do me a favour. Get back in my schoolbag, and when I give it a shake I want you to wriggle and hiss.’

‘Why should I do this?’

‘Because there’s a horrid boy who thinks you’re a snake, and if I can scare him maybe he’ll stop scaring me.’

‘I see,’ said Count Hedgehogula. ‘Very well. Since you have been so kind, I will help you.’

Just then there was an urgent knocking at the door accompanied by Ms Handel’s panicked voice. ‘Tracey, are you all right in there? Who are you talking to?’

‘Coming,’ Tracey called. ‘I was just soothing the snake.’

She opened her schoolbag and the hedgehog crawled inside.

‘Okay, I’m coming out now.’ Tracey opened the door to find the whole class crowded into the corridor.

‘Give me room,’ Tracey said, brandishing the bag. ‘It’s a big one.’

She gave the bag a little shake and the hedgehog squirmed and hissed obediently.

Everyone screamed; Stanley Blotson screamed loudest of all.

‘I found it under Stanley’s desk.’ She moved towards Stanley and he whimpered and flattened himself against the wall of the corridor.

‘It must have come from the nature reserve that backs onto the oval,’ Tracey continued. ‘I’m going to take it back there and release it.’

Tracey carried her bag across the oval to the edge of the bushland. There she crouched down and opened her bag. ‘Wait under this bush for a couple of hours and I’ll come back and fetch you after school,’ she told the hedgehog.

The hedgehog curled into a ball. ‘Very well,’ he murmured. ‘In the meantime, I will have a short rest and contemplate all the special milks I am yet to try.’

When Tracey returned to the classroom, everyone cheered.

After school, Tracey walked back across the oval to find Count Hedgehogula fast asleep under the bush where she’d left him. She picked him up very gently so as not t

o wake him (and so as not to hurt her hand on the prickles) and put him back into her schoolbag.

Back in her room at home she removed him. He stretched and yawned and looked around, nose twitching. ‘We are home,’ he said.

‘Well, my home, not yours. We need to get you back to Transylvania. Have you remembered how you got here?’

The hedgehog tilted his head to one side. ‘It doesn’t matter—I have decided to stay here with you. We have no special milk in Transylvania.’

‘I don’t know,’ Tracey said doubtfully. She was reluctant to share her room with a vampire, even if he only wanted to drink her milk.

Then she remembered what Stanley Blotson had said when she returned from the oval after releasing the ‘snake’. ‘You’re really brave, Tracey,’ he had said. ‘I promise I’ll never make fun of your name again.’

Tracey looked at the hedgehog. If Stanley should break his promise, it wouldn’t hurt to have a spiky secret weapon up her sleeve (or in her schoolbag).

‘Okay,’ she told Hedgehogula. ‘You can stay.’

‘Of course I can,’ said the hedgehog. ‘Now tell me more about this strawberry milk . . .’

DEATH

BY

CLOWN

by

Tristan

Bancks

‘Hey, Tom.’

Oh no.

It’s her.

On the phone.

Talking to me, Tom Weekly.

Why would she want to talk to me? I’m so nervous I want to throw up. This is the worst day of my life. I’m—

‘Tom?’

‘Yeah?’

Sasha. The cutest and smartest girl in Australia.

‘Are you okay?’ she asks.

What do you say to someone with eyes like blue sky, a voice like a mango smoothie and fresh, minty breath like an Arctic breeze? Not that I can smell it right now, but I can imagine it. So minty.

‘Tom?’

She sounds a bit annoyed. I can’t mess this up. I always mess things up with Sasha. Like the time I told her I was attacked by a giant feral guinea pig, who bit off my toe. Why am I such a—

‘We’ve got a spare front-row ticket to the circus tonight because my brother has to go to karate and Thalia and Leilani and Sophie and Brittany are busy. So do you want to come?’

Circus.

‘Tom?’

‘Huh?’

‘I’m asking you to the circus.’

‘Um . . .’ I’m sweating. I try to tell myself that it’s just because Sasha has called my house for the first time in our long on-again, off-again relationship. But I know that’s not it.

‘Mum’s calling me,’ Sasha says. ‘I’ve got to get ready. Do you want to come or not, Tom?’

My head froths with fear and panic—white-faced, red-nosed, fuzzy-haired, polka-dotted panic. But this is Sasha, my kryptonite.

‘Yes,’ I whisper.

‘“Yes” you’ll come?’

‘Yes,’ I say again, slightly louder, my voice breaking in an awkward way.

‘Great,’ she says. Although she doesn’t sound so sure now. ‘We’ll pick you up in 15 minutes.’

‘Fifteen,’ I repeat.

‘See you soon.’ Sasha hangs up.

‘I’m dead,’ I say to the beeping phone line. I have front-row seats to my own death.

I press ‘End’ and place the phone on the kitchen bench. I have never admitted this to anyone other than my mother, but I have a morbid fear of clowns. And when I say ‘morbid’, I mean ‘psychologically unhealthy’. And when I say ‘psychologically unhealthy’, I mean they freak me out. I can’t be near them. But, in everyday life, that’s fine. I just avoid little kids’ birthday parties, certain fast food outlets . . . and circuses. I have my coulrophobia (fear of clowns) under control.

Or at least I thought I did. Until about 17 seconds ago.

Mum comes into the kitchen, takes a bag of baby peas from the freezer and pours them into boiling water on the stove. ‘What’s wrong?’ she asks.

‘Sasha,’ I say.

‘What about her?’

‘She asked me out,’ I say.

‘Really! That’s great. I think you’re going to marry her one day.’

‘No,’ I say.

‘You’re not going to marry her?’

‘No. Circus.’

‘You’re not going to marry her at the circus?’

‘She asked me to go to the circus. In 15 minutes.’

‘Oh dear,’ she says. ‘Did you say no?’

I shake my head.

‘Well, it’s probably about time you got over it. You were three years old, Tom.’

I think back to the painting that Mum did. She hung it on the wall over my bed on the night of my third birthday. It still smelt like oil paint. I don’t think it ever really dried. The picture was of a tall, skinny clown in a blue polka-dot suit, red bow tie, fedora hat and evil eyes.

Every night from the age of three till I finally ripped the painting down when I was eight, he would slither out over the frame and into my bedroom. Some nights he would drop juggling balls onto my head for hours. Or strum an out-of-tune ukulele till four in the morning. Or sit right next to my ear and squeakily twist balloons into the shapes of werewolves, llamas and baboons.

I try to shake the clown from my thoughts, but there’s no way out of this. Girls like Sasha don’t just call up every night and ask guys like me to go out with them. My pop always said, ‘Never look a gift horse in the mouth.’ I never knew what he meant. But maybe this is it—not that Sasha is a horse. Although she does have kind of a long face and she sometimes has sliced apples for morning tea.

What if I’d said no and she asked some other guy like Zane Smithers? They would start going out together. They would end up getting married and having three kids and a labradoodle and a house overlooking the ocean with secret passages and revolving bookcases. All because I’d said no to going to the circus.

Over my dead body will I let that happen.

Dead body.

Mine.

The lights go down. Excitement swells—cheers and whistles and howls. Five hundred excited people are seated around the circus ring under the big top. Correction: 499 excited, one terrified.

‘What do you really want to see?’ Sasha asks, popping a piece of purple popcorn into her mouth. ‘I love the tightrope and the hula hoops, but I can’t wait for the clowns. They’re so funny. My favourite clown is . . .’

I tune out. Even the mention of the word ‘clown’ dries out my tongue and dampens my armpits. I squinch my eyes closed. I should be happy. I’m sitting next to Sasha. I can smell her minty breath, hear her mango smoothie voice, and our knees even touched a few minutes ago.

Yet I am filled with dread. The clown from the painting over my bed slithers back into my mind. Wherever I would go in my bedroom his eyes would follow. Sometimes I’d feel him watching me in other rooms, too. And at school. Even on holidays at the beach. There’s a phobia called anatidaephobia, which is the fear that—no matter where you are—a duck is watching you. Maybe that’s what I have, except with clowns. No matter what I said, for years Mum wouldn’t take the painting down. ‘Don’t be silly. Kids love clowns,’ she would say. ‘Don’t you like my painting?’

BOOM!

There is an explosion and a burst of flame that sends shockwaves through the crowd. My heart leaps into my head. Ten trapeze artists swing down from the big top. Five let go and the other five catch them in midair. Water fountains erupt all around the ring. A long-haired motorbike stunt rider soars over a jump and comes to land in front of us. She skids to a stop on the sawdust floor, rips off her helmet and raises her hand for silence.

‘Ladieeeees and gentlemennnnn! Welcome to Dingaling Brothers Circus, the most extraordinary display on Earth!’

‘That’s amazing,’ Sasha says, squeezing my hand.

It is. For the next hour, we are dazzled by unbelievable magic, stunts and acrobatics. And you know what? Not a singl

e clown. That is, until the lights go down after the human cannonball and I hear the honking sound of a cheap rubber horn. Every hair on my body stands to attention.

The lights snap on again. Not a slow fade but a violent snap.

A clown emerges from between the tall velvet curtains on the far side of the ring. He’s driving a tiny, kid-sized fire truck, his knees up around his ears. He waves to the crowd and blows his horn over and over again. As he moves closer and closer, I start to realise who he is. He is not just any clown. His hair is black and he wears a blue polka-dot suit, a red bow tie and a fedora hat. He is the sweaty, demonic clown from my mother’s painting.

I wet my pants. Not a lot, but definite leakage.

‘I have to go to the toilet,’ I tell Sasha, panicking. I stand and start to leave.

‘Nooo, this is my favourite part. I love the clowns. Please stay.’ She grabs my hand and pulls me back down. Clown-fear and Sasha-love battle to the death in my chest.

The crowd all around me is cracking up. As he zooms towards us I see that his truck has ‘Giggles’ written on the side. Giggles the Clown. He comes to a stop in front of us, his fire truck skidding in the sawdust. He falls out of the truck onto his face. The crowd erupts with laughter.

He stands, dusts himself off and looks directly at me.

He knows me.

He knows that I know that he knows me.

And he wants revenge for what I did to him.

Sweat stings my eyes. I slide down low in my chair.

Giggles motions to the crowd like he wants a helper. I slide down further in my seat, trying to become invisible. Giggles lowers his chin, glares at me through his thick brows, points and motions to me with one crooked, white-gloved finger.

Sasha claps wildly. ‘Tom! It’s you! He wants you!’

I can’t get up.

‘Just go!’ Sasha says.

I shake my head, cross my arms, squinch my eyes shut again.

‘Go on, young man!’ says the grandma sitting to my right.

‘How about you go, lady?’ I snap.

‘Get up, Tom!’ says Sasha’s dad. ‘What’s wrong with you?’

I shake my head. I have another flashback to the painting over my bed, the night he slipped out over the frame and tried to suffocate me with the world’s unfunniest clown fart. It smelt like dead mice, ginger beer and cauliflower. I was drowning in it. I held my breath for almost two minutes before I could swim to the surface of that deathly stench. I wrestled him back into the picture frame and ripped the painting off the wall.

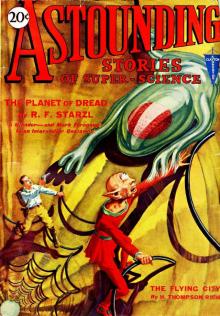

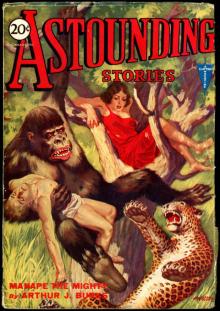

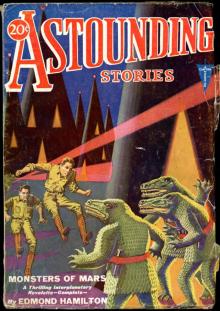

Astounding Stories, March, 1931

Astounding Stories, March, 1931 Astounding Stories, February, 1931

Astounding Stories, February, 1931 Futuria Fantasia, Spring 1940

Futuria Fantasia, Spring 1940 The King's Daughter and Other Stories for Girls

The King's Daughter and Other Stories for Girls Uncanny Tales

Uncanny Tales Masters of Noir: Volume Two

Masters of Noir: Volume Two Witty Pieces by Witty People

Witty Pieces by Witty People Sylvaneth

Sylvaneth Space Wolves

Space Wolves Hammerhal & Other Stories

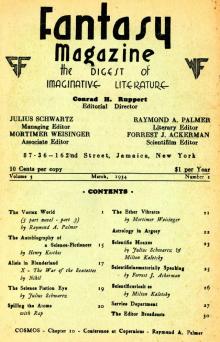

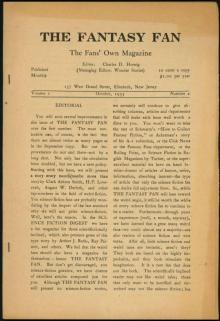

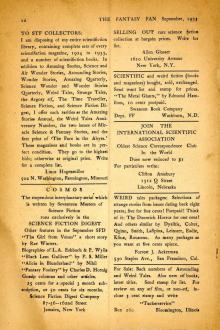

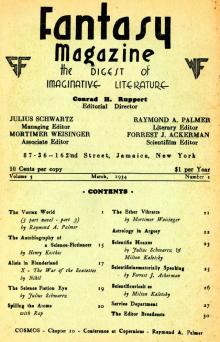

Hammerhal & Other Stories The Fantasy Fan, March, 1934

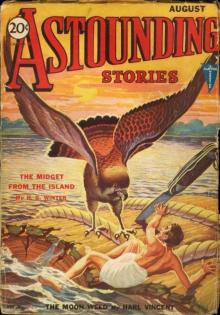

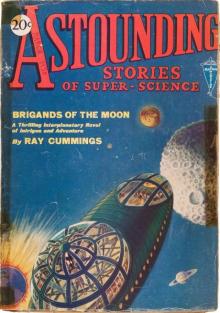

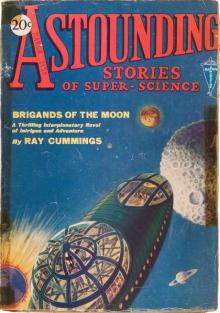

The Fantasy Fan, March, 1934 Astounding Stories of Super-Science, August 1930

Astounding Stories of Super-Science, August 1930 Astounding Stories, August, 1931

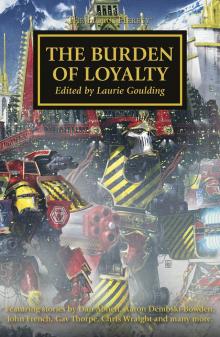

Astounding Stories, August, 1931 The Burden of Loyalty

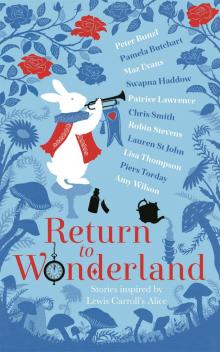

The Burden of Loyalty Return to Wonderland

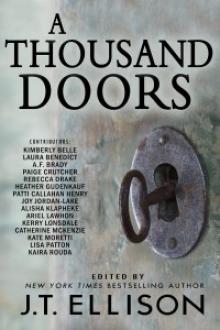

Return to Wonderland Anthology - A Thousand Doors

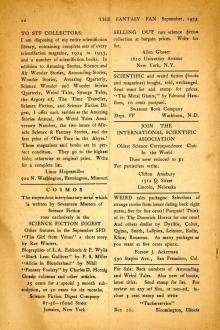

Anthology - A Thousand Doors The Fantasy Fan, October 1933

The Fantasy Fan, October 1933 Astounding Stories, June, 1931

Astounding Stories, June, 1931 Southern Stories

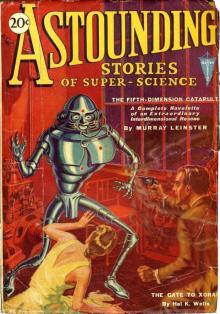

Southern Stories Astounding Stories of Super-Science, May, 1930

Astounding Stories of Super-Science, May, 1930 The Fantasy Fan December 1933

The Fantasy Fan December 1933 Adventures in Many Lands

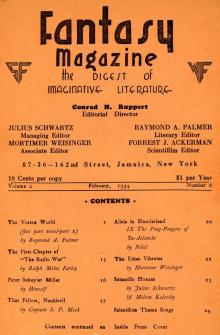

Adventures in Many Lands The Fantasy Fan February 1934

The Fantasy Fan February 1934 The Fantasy Fan November 1933

The Fantasy Fan November 1933 Astounding Stories, April, 1931

Astounding Stories, April, 1931 Fame and Fortune Weekly, No. 801, February 4, 1921

Fame and Fortune Weekly, No. 801, February 4, 1921 Astounding Stories of Super-Science, November, 1930

Astounding Stories of Super-Science, November, 1930 Astounding Stories of Super-Science January 1931

Astounding Stories of Super-Science January 1931 A Monk of Fife

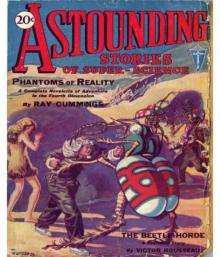

A Monk of Fife Astounding Stories of Super-Science September 1930

Astounding Stories of Super-Science September 1930 Astounding Stories of Super-Science July 1930

Astounding Stories of Super-Science July 1930 Astounding Stories of Super-Science, June, 1930

Astounding Stories of Super-Science, June, 1930 Astounding Stories of Super-Science, October, 1930

Astounding Stories of Super-Science, October, 1930 Astounding Stories of Super-Science, March 1930

Astounding Stories of Super-Science, March 1930 The Fantasy Fan January 1934

The Fantasy Fan January 1934 The Fantasy Fan September 1933

The Fantasy Fan September 1933 Astounding Stories of Super-Science February 1930

Astounding Stories of Super-Science February 1930 Astounding Stories, May, 1931

Astounding Stories, May, 1931 Strange Stories of Colonial Days

Strange Stories of Colonial Days Golden Age of Science Fiction Vol IX

Golden Age of Science Fiction Vol IX Astounding Stories of Super-Science, December 1930

Astounding Stories of Super-Science, December 1930 Evolutions: Essential Tales of the Halo Universe

Evolutions: Essential Tales of the Halo Universe Good Stories Reprinted from the Ladies' Home Journal of Philadelphia

Good Stories Reprinted from the Ladies' Home Journal of Philadelphia Dragons!

Dragons! Murder Takes a Holiday

Murder Takes a Holiday Legacies of Betrayal

Legacies of Betrayal STAR WARS: TALES FROM THE CLONE WARS

STAR WARS: TALES FROM THE CLONE WARS Strange New Worlds 2016

Strange New Worlds 2016 Lippincott's Magazine, August, 1885

Lippincott's Magazine, August, 1885 Golden Age of Science Fiction Vol X

Golden Age of Science Fiction Vol X Hot Stuff

Hot Stuff Santa Wore Spurs

Santa Wore Spurs Paranormal Erotica

Paranormal Erotica Tangled Hearts: A Menage Collection

Tangled Hearts: A Menage Collection Sweet Tea and Jesus Shoes

Sweet Tea and Jesus Shoes The Journey Prize Stories 25

The Journey Prize Stories 25 Wild Western Tales 2: 101 Classic Western Stories Vol. 2 (Civitas Library Classics)

Wild Western Tales 2: 101 Classic Western Stories Vol. 2 (Civitas Library Classics) (5/15) The Golden Age of Science Fiction Volume V: An Anthology of 50 Short Stories

(5/15) The Golden Age of Science Fiction Volume V: An Anthology of 50 Short Stories (4/15) The Golden Age of Science Fiction Volume IV: An Anthology of 50 Short Stories

(4/15) The Golden Age of Science Fiction Volume IV: An Anthology of 50 Short Stories Ten Journeys

Ten Journeys The Boss

The Boss The Penguin Book of French Poetry

The Penguin Book of French Poetry Golden Age of Science Fiction Vol VIII

Golden Age of Science Fiction Vol VIII His Cinderella Housekeeper 3-in-1

His Cinderella Housekeeper 3-in-1 The Magazine of Fantasy & Science Fiction - July/August 2016

The Magazine of Fantasy & Science Fiction - July/August 2016 PYRATE CTHULHU - Tales of the Cthulhu Mythos (vol.2)

PYRATE CTHULHU - Tales of the Cthulhu Mythos (vol.2) Tales from a Master's Notebook

Tales from a Master's Notebook April 1930

April 1930 New Erotica 6

New Erotica 6 Damocles

Damocles The Longest Night Vol. 1

The Longest Night Vol. 1 The Golden Age of Science Fiction Volume VI: An Anthology of 50 Short Stories

The Golden Age of Science Fiction Volume VI: An Anthology of 50 Short Stories (1/15) The Golden Age of Science Fiction: An Anthology of 50 Short Stories

(1/15) The Golden Age of Science Fiction: An Anthology of 50 Short Stories Eye of Terra

Eye of Terra ONCE UPON A REGENCY CHRISTMAS

ONCE UPON A REGENCY CHRISTMAS Nexus Confessions

Nexus Confessions Passionate Kisses

Passionate Kisses War Without End

War Without End Doctor Who: Time Lord Fairy Tales

Doctor Who: Time Lord Fairy Tales Gotrek and Felix: The Anthology

Gotrek and Felix: The Anthology WESTERN CHRISTMAS PROPOSALS

WESTERN CHRISTMAS PROPOSALS The Journey Prize Stories 27

The Journey Prize Stories 27 The Silent War

The Silent War Liaisons

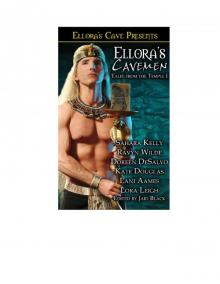

Liaisons Ellora's Cavemen: Tales from the Temple IV

Ellora's Cavemen: Tales from the Temple IV Ellora's Cavemen: Tales from the Temple II

Ellora's Cavemen: Tales from the Temple II Some of the Best From Tor.com, 2013 Edition: A Tor.Com Original

Some of the Best From Tor.com, 2013 Edition: A Tor.Com Original Urban Occult

Urban Occult Fractures

Fractures The Stories: Five Years of Original Fiction on Tor.com

The Stories: Five Years of Original Fiction on Tor.com The Penguin Book of Modern British Short Stories

The Penguin Book of Modern British Short Stories Mortarch of Night

Mortarch of Night The Portable Nineteenth-Century African American Women Writers

The Portable Nineteenth-Century African American Women Writers The Golden Age of Science Fiction Volume VII: An Anthology of 50 Short Stories

The Golden Age of Science Fiction Volume VII: An Anthology of 50 Short Stories Holy Bible: King James Version, The

Holy Bible: King James Version, The Eight Rooms

Eight Rooms sanguineangels

sanguineangels DarkNightsWithaBillionaireBundle

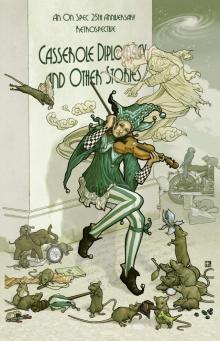

DarkNightsWithaBillionaireBundle Casserole Diplomacy and Other Stories

Casserole Diplomacy and Other Stories How I Survived My Summer Vacation

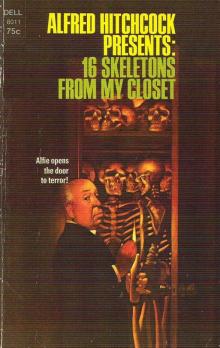

How I Survived My Summer Vacation Alfred Hitchcock Presents: 16 Skeletons From My Closet

Alfred Hitchcock Presents: 16 Skeletons From My Closet Lords, Ladies, Butlers and Maids

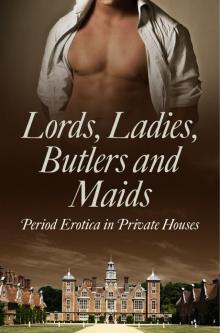

Lords, Ladies, Butlers and Maids The B4 Leg

The B4 Leg Ellora's Cavemen: Tales from the Temple I

Ellora's Cavemen: Tales from the Temple I 2014 Campbellian Anthology

2014 Campbellian Anthology There Is Only War

There Is Only War Obsidian Alliances

Obsidian Alliances 12 Gifts for Christmas

12 Gifts for Christmas Scary Holiday Tales to Make You Scream

Scary Holiday Tales to Make You Scream 25 For 25

25 For 25 The Plagues of Orath

The Plagues of Orath And Then He Kissed Me

And Then He Kissed Me Star Trek - Gateways 7 - WHAT LAY BEYOND

Star Trek - Gateways 7 - WHAT LAY BEYOND Laugh Your Head Off Again and Again

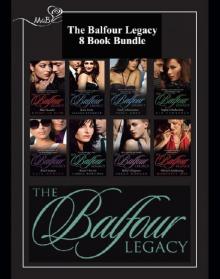

Laugh Your Head Off Again and Again The Balfour Legacy

The Balfour Legacy Golden Age of Science Fiction Vol XI

Golden Age of Science Fiction Vol XI (3/15) The Golden Age of Science Fiction Volume III: An Anthology of 50 Short Stories

(3/15) The Golden Age of Science Fiction Volume III: An Anthology of 50 Short Stories Shas'o

Shas'o Astounding Science Fiction Stories: An Anthology of 350 Scifi Stories Volume 2 (Halcyon Classics)

Astounding Science Fiction Stories: An Anthology of 350 Scifi Stories Volume 2 (Halcyon Classics) Twists in Time

Twists in Time Meduson

Meduson The Magazine of Fantasy & Science Fiction - August 1980

The Magazine of Fantasy & Science Fiction - August 1980 The Journey Prize Stories 22

The Journey Prize Stories 22 The Book that Made Me

The Book that Made Me Angels of Death Anthology

Angels of Death Anthology Ask the Bones

Ask the Bones Emergence

Emergence Beware the Little White Rabbit

Beware the Little White Rabbit Xcite Delights Book 1

Xcite Delights Book 1 Where flap the tatters of the King

Where flap the tatters of the King The Journey Prize Stories 21

The Journey Prize Stories 21 Tales of the Slayer, Volume II

Tales of the Slayer, Volume II Glass Empires

Glass Empires Golden Age of Science Fiction Vol XII

Golden Age of Science Fiction Vol XII (2/15) The Golden Age of Science Fiction Volume II: An Anthology of 50 Short Stories

(2/15) The Golden Age of Science Fiction Volume II: An Anthology of 50 Short Stories Fairytale Collection

Fairytale Collection Angels!

Angels! Golden Age of Science Fiction Vol XIII

Golden Age of Science Fiction Vol XIII