Legacies of Betrayal Read online

Page 5

It took me longer to travel down from the heights than it had taken me to climb them. I stumbled often, slipping down loose banks of scree with my numb limbs. When the sun came up fully, my pace improved. I stopped only as I neared the level of the plains, back at the head of the valley I had walked up the previous day.

I saw what remained of my escort’s camp from a distance, and immediately knew that something was wrong. I crouched down beside the trunk of a tree and screwed my eyes up, peering down a long, meandering river-course to where the khan’s warriors had left me.

The aduun were gone. I saw bodies on the ground in awkward poses. I felt my heartbeat quicken. Twelve warriors had come with me into the mountains; twelve bodies lay on the ground around the remains of the fire.

I moved closer to the trunk. I had no idea what to do. I knew that I needed to get back to the khan’s side, but also that I was now dangerously exposed. The plains were no place to travel alone – there were no hiding places out on the Altak.

I would have waited there longer had I not heard them coming for me. From somewhere higher up, I heard the snap of branches and the loud, careless voices of soldiers singing in a language I didn’t know.

A single word flashed through my mind, chilling my blood.

Khitan.

Somehow I had passed them on the way down – they must have been hunting for me up in the highlands, and only dumb luck had carried me past them undetected.

They were close, rooting through the undergrowth. For all I knew there were more of them, crawling across the Ulaav like ants out of a kicked nest.

I didn’t stop to think. I ran, darting out of the cover of the trees and tearing down to where the khan’s men had been killed. Even as I skidded and slipped down the steep path I could hear the cries of the Khitan as they caught sight of me and lumbered into pursuit.

I ran as hard as I could, feeling my lungs burn as my breathing became heavy. I ran like an animal runs, fuelled by fear. I didn’t look back.

My only thought was to get clear of the hunters, to get out into open ground, to find the khan. He led the mightiest warband on the Altak, one that grew every day. He would be able to protect me even if the Khitan who chased me numbered in hundreds.

But I had to find him. Somehow, I had to stay alive long enough to find him.

I knew his reputation. I knew that he moved around without warning, shifting from place to place to keep his enemies guessing. Even Uig, who could see all paths, had called him the berkut – the hunting eagle, the far-ranger, the elusive.

Such thoughts did not help. I forced my mind to remain fixed on the task. I kept running, leaping over briars and swerving around boulders. The voices of my hunters followed me, and I heard their boots thud against the earth.

I had no more choices to make. All the ways of the future had narrowed down to a single course, and I could do nothing but follow it.

I ran down from the mountains and out into the plains-grass beyond. I had no plan, no allies, and little hope. All I had was my life, newly enriched with visions of another world. I intended to fight for it, but did not yet know how.

IV. Shiban

We knew they would make a fight of it in the end. Once there was nowhere left for them to run, they turned and faced us.

They had chosen a good place to make their stand. High in Chondax’s northern hemisphere, the endless white plains eventually crumpled into a maze of ravines and jagged peaks, a scar on the open face of the world that was visible from space. We had never penetrated far into that region, opting to clear the orks from the plains first. It was natural defensive terrain – hard to enter, easy to hide in.

When our auspex operators had seen it from orbit, they had called it teghazi: the Grinder. I think that was their idea of a joke.

I stood in the saddle, looking out at the first of the many cliffs rising up against the northern horizon. I could see long trails of smoke rising from the heart of the rock cluster.

I raised magnoculars to my eyes and zoomed in. Metal artefacts had been placed amid the stone, glinting in the bright sunlight. The orks had built walls across narrow ravine entrances, using material stripped from their own vehicles. Knowing that they would not need them again, they had turned their only means of movement into their only means of defence.

I approved of that.

‘They are well positioned,’ I said scanning across the fortifications.

‘They are,’ said Torghun, standing beside me and also using magnoculars. Our two brotherhoods spread out behind us in their assault formations, waiting for the order to advance. ‘I see fixed weapons. They’ve got numbers.’

I swept my view across to the nearest of the ravine mouths facing us. Walls were clearly visible, placed further back between the jaws of the ravine and strung across the gully floor in a line of metal panels and bolted struts. I could see orks patrolling along the top of them. As Torghun had noted, there were weapon towers lodged higher up the ravine slopes.

‘This will be difficult,’ I said.

Torghun laughed.

‘It will, Shiban.’

In the days since we had joined forces, I had not found it easy to understand Torghun. Sometimes he would laugh and I would not know why. Sometimes I would laugh and he would look at me strangely.

He was a good warrior, and I think we both respected one another when it came to blades. We had destroyed two more convoys before we had arrived at the Grinder, and I had seen at first-hand how his brotherhood fought.

They were more structured than we were. I rarely gave my brothers orders once an engagement started: I trusted them to look after themselves. Torghun gave his warriors orders all the time, and they followed them instantly. They used speed, just as we did, but were quicker to adopt fire positions when the combat became more static.

Some tactics I never saw them adopt. They never pulled back, feigning retreat in order to draw out the enemy.

‘We don’t retreat,’ he had said.

‘It is effective,’ I had replied.

‘More effective to let them know you’ll never do it,’ he had said, smiling. ‘When the Luna Wolves go to war, the enemy knows they’ll never stop coming forward, all the time, wave after wave, until it’s over. It’s a powerful reputation to have.’

I could hardly argue against the record of the Warmaster’s Legion. I had seen them fight. They were impressive.

So, as I scanned the greenskins’ defences, I had little idea what Torghun would propose. I feared that he would advocate waiting until other minghan reached our position, and I did not relish disputing with him. I wished to maintain our momentum, since I knew that other brotherhoods would already be entering combat on the far sides of the huge ravine complex. If we were to gain the honour of fighting alongside the Khagan – who would surely be at the heart of the action – then we would have to remain at the forefront of the closing circle.

‘I do not wish to wait,’ I said firmly, putting my magnoculars down and looking at Torghun. ‘We can break them.’

Torghun did not reply immediately. He continued looking out at the distant cliff-faces, scanning for weaknesses. Eventually he stopped and looked at me.

He grinned. I had seen that grin before; it was one of the few gestures we shared. He grinned before he entered battle, just as I did.

‘I think you’re right, brother,’ he said.

We came in hard over on the left flank of our target, building quickly to attack speed, burning across the plains in close-packed squadrons. I crouched low in the saddle, gripping the controls of my mount, feeling the animal grind of the engines, the hard vibrations of the blazing thrusters, the violent urgings of the caged machine-spirit. My brothers spread out on either side of me, speeding across the white earth in perfect formation.

The ravine entrance we had chosen was narrow – two hundred metres across, as the auspex read it – and clogged with defenders. We skirted wide, using the cliffs jutting out on either side of its jaws to mask ou

r approach. I felt my braided hair whip against my shoulder guards. We ate up the ground, devouring it, tearing it up in a blaze of furious motion.

We had timed our run to coincide with the rising of the third sun. As it emerged behind us, flaring silver, blinding the defenders to our advance, I cried out to greet it.

‘For the Khagan!’ I roared.

For the Khagan! came the thunderous, rapturous response.

I relished that: five hundred of us on the charge, thundering into range at searing velocity, wreathed in a dazzling corona of silver and gold, our jetbikes bucking and swerving. I saw Jochi alongside me, hurling out battle-cries in Korchin, his eyes alive with bloodlust. Batu, Hasi, the rest of my minghan-keshig, they all hunkered forward, all straining at the leash.

The first volleys of defensive fire snapped and bounced around us, a motley rain of solid rounds and crude energy bolts. We weaved amongst them, goading our jetbikes ever faster, glorying in their superb poise, rush and tilt.

The jutting cliffs zoomed up to meet us. We came around, leaning heavily, scraping the ground before racing into the mouth of the valley beyond.

We cleared the cover of the cliffs, and our senses were overrun by a crashing, coruscating storm of incoming fire. A hurricane of projectiles spiralled out of the walls ahead of us, blowing up in our faces and hurling bikes end-over-end.

A rider close to me took a direct hit. His mount disintegrated, ripped apart in a shower of metal and promethium, flying crazily across the ravine and slamming into the ground in a smear of flame and debris. Warriors were hurled from their saddles, had holes punched through their armour, were sent careering into the rock walls where they exploded in massive, blooming fireballs.

None of us slowed. We hurtled down the ravine, maintaining attack speed, ducking and swaying around the lines of fire, rising above it to widen the field before plunging back down to ground level and letting it streak over our heads.

I poured on more power, feeling my bike shudder with the strain. The land around was a mess of streaked, blurred white – only the metal walls ahead remained in focus. I felt shots graze against my bike’s forward armour, nearly throwing me out of line. More of my brothers went down as the torrent of flak and shrapnel took them.

The walls screamed closer. I saw orks leaping about on top of them, waving their weapons and roaring challenges. Gun towers zeroed in on us, swivelling to let loose before we hit them.

We opened up. A pounding cacophony of heavy bolter fire snarled out, filling the ravine with a ragged hail of ruinous, withering destruction. The walls disappeared behind bursting clouds of explosive devastation. Metal plates snapped and dented, blowing apart in a hail of splinters. I saw greenskins thrown high into the air, their bodies shredded open by the flood of shells.

Just then, as he had promised they would, Torghun’s heavy support opened fire. His auxiliary squads had broken off, making the most of the screen of our frontal assault and securing high ground on either side of the ravine. They possessed tools of devastation that we didn’t carry: lascannons, missile launchers, barrel-cycling autocannons, even an esoteric beam-weapon they called a ‘volkite culverin’, something I had never seen before.

Their barrage was devastating, igniting the air around it, cracking into the barrier ahead of us and dousing it in a cataract of raging, swimming energy. Huge rents were blown open. Panels, struts and spars went spinning, tearing through the curtains of flame. Missiles streaked in, angling through the storm of destruction, whistling past us and crashing into the burning ork lines beyond. Neon-bright spears of energy snapped and fizzed, sending lurid glows racing along the rock walls.

I picked my target, aiming for a fire-rimed breach in the walls. I hurtled through the inferno towards it, feeling sheets of flame sweep and shimmer across me. I swung over almost to the horizontal, letting an ork missile whine past. Then I rocked back upright, kicked in a final boost and shot clean through the ragged gap in the walls.

Something must have hit me as I burst through the defences. I felt a thud somewhere under the bike’s undercarriage, and it spun away hard right. I grappled with the controls, barely arresting a fatal spin.

The world slurred around me, rocking and spiralling. I could hear other jetbikes streak through the gouges in the walls and turn their heavy bolters upon the defenders. I had a brief glimpse of the ravine on the far side – studded with ramshackle barricades and choke-points, crawling with whole gangs of orks, all of them teeming with brutish fury. Gunfire, thick and incessant, criss-crossed the narrow defile, broken by airborne bursts and flak clouds.

I swung around, diving under a flurry of incoming rounds before gunning my faltering drive unit again. Trailing smoke, my bike lurched and bucked before it gave out completely, throwing me into a sharp dive.

The rocky ground rushed toward me in a sickening plummet. I leapt, hurling myself from the saddle. I hit the ground hard and rolled away, hearing the sharp crack of my bike impacting on the ravine floor, followed by the whoosh and bang of its fuel tanks going up.

I jumped to my feet as wreckage rained down around me, my glaive already poised. I’d come about two hundred metres beyond the walls. I could see the barrier from the other side – the scaffolding collapsing, the ammo-lifters going up like torches, the shuddering impacts from Torghun’s punishing long-range fire. Bodies were everywhere, falling from the tottering parapets, swarming over the rock. The air was dense with an incredible fog of noise – screams, bellows, jetbike engines throttling up, cannons discharging.

Greenskins were already homing in, knots of them, firing at me from makeshift carbines and pistols and lumbering to the charge. I felt the ping and crack of the solid rounds as they ricocheted from my armour. I heard their bestial, throaty war-challenges. I smelled the stench of their anger.

I flicked the guan dao’s energy field on, feeling the shaft tremble as it powered up.

By the time they closed on me, I was more than ready.

I whipped my upper body around, punching out with the guan dao. The crackling edge dug deep into the leading ork’s face, slicing open its flesh and sending the creature staggering backwards in a bloody, flailing froth.

Another threw a wild hack with a cleaver, biting into my pauldron but failing to penetrate the ceramite. I plunged my glaive into its stomach, twisting it round, liquefying the hard flesh. More piled in, and I tore through them, spinning and stabbing. The guan dao sang in my hands, spiralling around me in a glistening net of sparkling power. Greenskins were thrown clear, their armour cracked, their bodies broken.

I barely heard the thunder and rush of the battle around me. My mind drilled down to the core of combat, and I lost myself in it, unaware of the flaming sky above me, unaware of the scores of jetbikes tearing past with their weapons blazing.

I rotated, swiping a greenskin’s head clean off, then darted back, cracking the heel of the guan dao into the skull of another. I eviscerated, gouged, ripped, snapped and blinded, boosted by my armour, my strength, my vicious artistry.

One of them, a huge tusked monster with rusty iron pauldrons, threw itself bodily at me, somehow evading my blade and getting under my guard. We collided with a jarring thud and both sprawled to the ground. The creature landed on top of me, and the stink of it clogged in my nostrils. It butted my face, and the force of the blow cracked my head back. My vision swam, and I saw blood wash across my eyes.

I was pinned. I tried to bring the glaive, still clutched in my left hand, around to dig into the monster’s back. It saw the movement and twisted to block it with its own weapon – a spiked maul already covered in a slick of blood. The guan dao’s energy field detonated on contact, shattering the maul-head in a shower of metal fragments, lacerating both of us.

The greenskin jerked back up, loosening its grip, clawing at its eyes and bellowing with pain. With a huge heave, I pushed it clear and swung the glaive round in a whip-lash figure, aiming for the stomach. The blade cut deep, driving between armour plates and severi

ng the ork down to the spine. I wrenched the shaft back out, hauling hard with both hands. The monster bisected, its torso disintegrating in a sucking swamp of ripped muscle, blood and bone.

I heard another movement from behind me and whirled around, primed to swing again.

Jochi stood there, his armour streaked with red, his bolter in hand, surrounded by heaps of ork corpses. Behind him I could see the ramshackle barrier coming down, slowly toppling as the fires ripped through it. My brothers were everywhere, harrying, pursuing, slaying, tearing like vengeful ghosts through the teeming hordes.

‘This is good hunting, my khan!’ Jochi observed, laughing heartily.

I joined him in his mirth, feeling the cuts across my face open up.

‘And not done yet!’ I shouted, shaking the blood from my blade, turning to find more prey. Jetbikes shot overhead, powered onwards by whooping, shrieking riders.

Under their wheeling shadows, we launched back into the fight.

The battle in the ravine did not let up once the walls had been broken. More barriers had been strung across the winding gorges ahead, clogging the routes leading deeper into the interior of the Grinder. Greenskins had dug themselves in wherever they could. They poured out of their refuges, lurching at us in waves, scrambling over the rocky ravine floor in their haste to blood us. We were dragged deep into melee combat, assailed from all sides as we cut our way down the long defiles and gulches.

Many of my brothers remained mounted, sweeping up and down the long valley and taking out enemy fire positions with a speed the defenders could not match. Others advanced on foot, as I did, racing to bring combat to the greenskins.

When we got in close, we smelled the blood and sweat on our prey. We heard their broken roars and felt the tremors of their massed tread. Even as we cut them down we relished their skill and their savage bravery, appreciating what superlative creatures we were purging from existence.

Jochi had been right. When the last greenskin was gone, it would be a sad day.

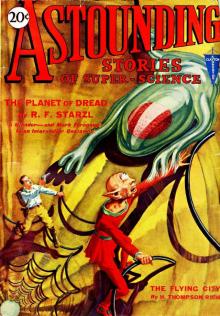

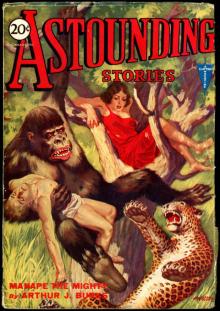

Astounding Stories, March, 1931

Astounding Stories, March, 1931 Astounding Stories, February, 1931

Astounding Stories, February, 1931 Futuria Fantasia, Spring 1940

Futuria Fantasia, Spring 1940 The King's Daughter and Other Stories for Girls

The King's Daughter and Other Stories for Girls Uncanny Tales

Uncanny Tales Masters of Noir: Volume Two

Masters of Noir: Volume Two Witty Pieces by Witty People

Witty Pieces by Witty People Sylvaneth

Sylvaneth Space Wolves

Space Wolves Hammerhal & Other Stories

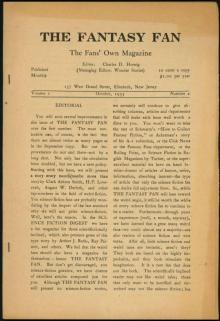

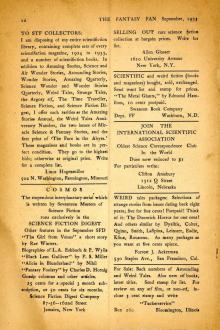

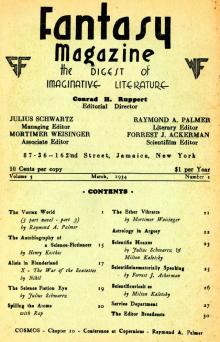

Hammerhal & Other Stories The Fantasy Fan, March, 1934

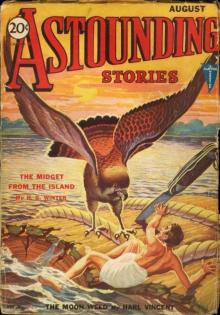

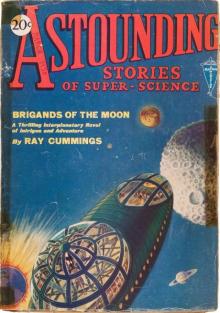

The Fantasy Fan, March, 1934 Astounding Stories of Super-Science, August 1930

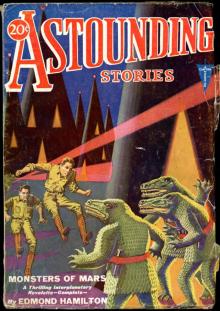

Astounding Stories of Super-Science, August 1930 Astounding Stories, August, 1931

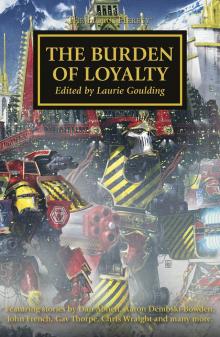

Astounding Stories, August, 1931 The Burden of Loyalty

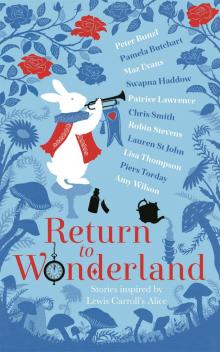

The Burden of Loyalty Return to Wonderland

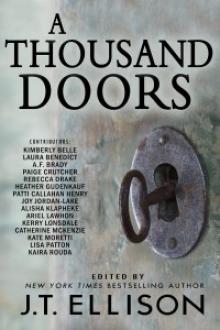

Return to Wonderland Anthology - A Thousand Doors

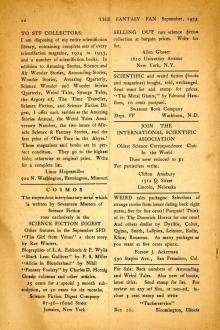

Anthology - A Thousand Doors The Fantasy Fan, October 1933

The Fantasy Fan, October 1933 Astounding Stories, June, 1931

Astounding Stories, June, 1931 Southern Stories

Southern Stories Astounding Stories of Super-Science, May, 1930

Astounding Stories of Super-Science, May, 1930 The Fantasy Fan December 1933

The Fantasy Fan December 1933 Adventures in Many Lands

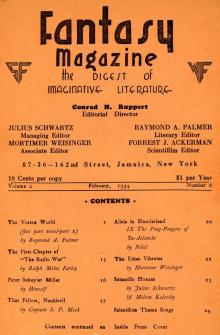

Adventures in Many Lands The Fantasy Fan February 1934

The Fantasy Fan February 1934 The Fantasy Fan November 1933

The Fantasy Fan November 1933 Astounding Stories, April, 1931

Astounding Stories, April, 1931 Fame and Fortune Weekly, No. 801, February 4, 1921

Fame and Fortune Weekly, No. 801, February 4, 1921 Astounding Stories of Super-Science, November, 1930

Astounding Stories of Super-Science, November, 1930 Astounding Stories of Super-Science January 1931

Astounding Stories of Super-Science January 1931 A Monk of Fife

A Monk of Fife Astounding Stories of Super-Science September 1930

Astounding Stories of Super-Science September 1930 Astounding Stories of Super-Science July 1930

Astounding Stories of Super-Science July 1930 Astounding Stories of Super-Science, June, 1930

Astounding Stories of Super-Science, June, 1930 Astounding Stories of Super-Science, October, 1930

Astounding Stories of Super-Science, October, 1930 Astounding Stories of Super-Science, March 1930

Astounding Stories of Super-Science, March 1930 The Fantasy Fan January 1934

The Fantasy Fan January 1934 The Fantasy Fan September 1933

The Fantasy Fan September 1933 Astounding Stories of Super-Science February 1930

Astounding Stories of Super-Science February 1930 Astounding Stories, May, 1931

Astounding Stories, May, 1931 Strange Stories of Colonial Days

Strange Stories of Colonial Days Golden Age of Science Fiction Vol IX

Golden Age of Science Fiction Vol IX Astounding Stories of Super-Science, December 1930

Astounding Stories of Super-Science, December 1930 Evolutions: Essential Tales of the Halo Universe

Evolutions: Essential Tales of the Halo Universe Good Stories Reprinted from the Ladies' Home Journal of Philadelphia

Good Stories Reprinted from the Ladies' Home Journal of Philadelphia Dragons!

Dragons! Murder Takes a Holiday

Murder Takes a Holiday Legacies of Betrayal

Legacies of Betrayal STAR WARS: TALES FROM THE CLONE WARS

STAR WARS: TALES FROM THE CLONE WARS Strange New Worlds 2016

Strange New Worlds 2016 Lippincott's Magazine, August, 1885

Lippincott's Magazine, August, 1885 Golden Age of Science Fiction Vol X

Golden Age of Science Fiction Vol X Hot Stuff

Hot Stuff Santa Wore Spurs

Santa Wore Spurs Paranormal Erotica

Paranormal Erotica Tangled Hearts: A Menage Collection

Tangled Hearts: A Menage Collection Sweet Tea and Jesus Shoes

Sweet Tea and Jesus Shoes The Journey Prize Stories 25

The Journey Prize Stories 25 Wild Western Tales 2: 101 Classic Western Stories Vol. 2 (Civitas Library Classics)

Wild Western Tales 2: 101 Classic Western Stories Vol. 2 (Civitas Library Classics) (5/15) The Golden Age of Science Fiction Volume V: An Anthology of 50 Short Stories

(5/15) The Golden Age of Science Fiction Volume V: An Anthology of 50 Short Stories (4/15) The Golden Age of Science Fiction Volume IV: An Anthology of 50 Short Stories

(4/15) The Golden Age of Science Fiction Volume IV: An Anthology of 50 Short Stories Ten Journeys

Ten Journeys The Boss

The Boss The Penguin Book of French Poetry

The Penguin Book of French Poetry Golden Age of Science Fiction Vol VIII

Golden Age of Science Fiction Vol VIII His Cinderella Housekeeper 3-in-1

His Cinderella Housekeeper 3-in-1 The Magazine of Fantasy & Science Fiction - July/August 2016

The Magazine of Fantasy & Science Fiction - July/August 2016 PYRATE CTHULHU - Tales of the Cthulhu Mythos (vol.2)

PYRATE CTHULHU - Tales of the Cthulhu Mythos (vol.2) Tales from a Master's Notebook

Tales from a Master's Notebook April 1930

April 1930 New Erotica 6

New Erotica 6 Damocles

Damocles The Longest Night Vol. 1

The Longest Night Vol. 1 The Golden Age of Science Fiction Volume VI: An Anthology of 50 Short Stories

The Golden Age of Science Fiction Volume VI: An Anthology of 50 Short Stories (1/15) The Golden Age of Science Fiction: An Anthology of 50 Short Stories

(1/15) The Golden Age of Science Fiction: An Anthology of 50 Short Stories Eye of Terra

Eye of Terra ONCE UPON A REGENCY CHRISTMAS

ONCE UPON A REGENCY CHRISTMAS Nexus Confessions

Nexus Confessions Passionate Kisses

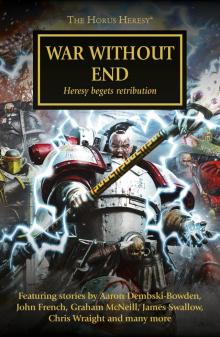

Passionate Kisses War Without End

War Without End Doctor Who: Time Lord Fairy Tales

Doctor Who: Time Lord Fairy Tales Gotrek and Felix: The Anthology

Gotrek and Felix: The Anthology WESTERN CHRISTMAS PROPOSALS

WESTERN CHRISTMAS PROPOSALS The Journey Prize Stories 27

The Journey Prize Stories 27 The Silent War

The Silent War Liaisons

Liaisons Ellora's Cavemen: Tales from the Temple IV

Ellora's Cavemen: Tales from the Temple IV Ellora's Cavemen: Tales from the Temple II

Ellora's Cavemen: Tales from the Temple II Some of the Best From Tor.com, 2013 Edition: A Tor.Com Original

Some of the Best From Tor.com, 2013 Edition: A Tor.Com Original Urban Occult

Urban Occult Fractures

Fractures The Stories: Five Years of Original Fiction on Tor.com

The Stories: Five Years of Original Fiction on Tor.com The Penguin Book of Modern British Short Stories

The Penguin Book of Modern British Short Stories Mortarch of Night

Mortarch of Night The Portable Nineteenth-Century African American Women Writers

The Portable Nineteenth-Century African American Women Writers The Golden Age of Science Fiction Volume VII: An Anthology of 50 Short Stories

The Golden Age of Science Fiction Volume VII: An Anthology of 50 Short Stories Holy Bible: King James Version, The

Holy Bible: King James Version, The Eight Rooms

Eight Rooms sanguineangels

sanguineangels DarkNightsWithaBillionaireBundle

DarkNightsWithaBillionaireBundle Casserole Diplomacy and Other Stories

Casserole Diplomacy and Other Stories How I Survived My Summer Vacation

How I Survived My Summer Vacation Alfred Hitchcock Presents: 16 Skeletons From My Closet

Alfred Hitchcock Presents: 16 Skeletons From My Closet Lords, Ladies, Butlers and Maids

Lords, Ladies, Butlers and Maids The B4 Leg

The B4 Leg Ellora's Cavemen: Tales from the Temple I

Ellora's Cavemen: Tales from the Temple I 2014 Campbellian Anthology

2014 Campbellian Anthology There Is Only War

There Is Only War Obsidian Alliances

Obsidian Alliances 12 Gifts for Christmas

12 Gifts for Christmas Scary Holiday Tales to Make You Scream

Scary Holiday Tales to Make You Scream 25 For 25

25 For 25 The Plagues of Orath

The Plagues of Orath And Then He Kissed Me

And Then He Kissed Me Star Trek - Gateways 7 - WHAT LAY BEYOND

Star Trek - Gateways 7 - WHAT LAY BEYOND Laugh Your Head Off Again and Again

Laugh Your Head Off Again and Again The Balfour Legacy

The Balfour Legacy Golden Age of Science Fiction Vol XI

Golden Age of Science Fiction Vol XI (3/15) The Golden Age of Science Fiction Volume III: An Anthology of 50 Short Stories

(3/15) The Golden Age of Science Fiction Volume III: An Anthology of 50 Short Stories Shas'o

Shas'o Astounding Science Fiction Stories: An Anthology of 350 Scifi Stories Volume 2 (Halcyon Classics)

Astounding Science Fiction Stories: An Anthology of 350 Scifi Stories Volume 2 (Halcyon Classics) Twists in Time

Twists in Time Meduson

Meduson The Magazine of Fantasy & Science Fiction - August 1980

The Magazine of Fantasy & Science Fiction - August 1980 The Journey Prize Stories 22

The Journey Prize Stories 22 The Book that Made Me

The Book that Made Me Angels of Death Anthology

Angels of Death Anthology Ask the Bones

Ask the Bones Emergence

Emergence Beware the Little White Rabbit

Beware the Little White Rabbit Xcite Delights Book 1

Xcite Delights Book 1 Where flap the tatters of the King

Where flap the tatters of the King The Journey Prize Stories 21

The Journey Prize Stories 21 Tales of the Slayer, Volume II

Tales of the Slayer, Volume II Glass Empires

Glass Empires Golden Age of Science Fiction Vol XII

Golden Age of Science Fiction Vol XII (2/15) The Golden Age of Science Fiction Volume II: An Anthology of 50 Short Stories

(2/15) The Golden Age of Science Fiction Volume II: An Anthology of 50 Short Stories Fairytale Collection

Fairytale Collection Angels!

Angels! Golden Age of Science Fiction Vol XIII

Golden Age of Science Fiction Vol XIII