The Book that Made Me Read online

Page 5

This is the part where I confess the real reason I was so delighted by the youngsters’ reaction to the story. I was delighting in the story too. Like them, I had never come across it before. And so to enjoy it for the first time in the company of my children was particularly fine. And enjoy it I did. Because Dahl is a master of the revolting and the unspeakable. I remember as a child being read to from a great tome of tales from the Brothers Grimm. We angst in our modern times over what does and doesn’t constitute appropriate fare for the young, yet I still recall how confronting Hansel and Gretel’s abandonment was. But, I dealt with it and by the end of the tale the old woman had been murdered, the evil stepmother sent away and all was well. Our instinct is to keep our children safe from horror, and from humour that might hint at any kind of viciousness, but again, there is beauty to be uncovered when our ideals are compromised. In George’s Marvellous Medicine, there is no politeness offered. Grandma may be the family’s elder, but she is afforded no respect. Rather, she is described in the opening passages as selfish and grumpy, and her puckered mouth is compared to a dog’s bottom.

How we children laughed.

To be clear, this is not a tale where enemies learn, in time, to begrudgingly respect one another. George does not learn of his grandma’s kinder side, or discover the pains in her past that have made her the way she is. Nor does some act of selflessness from the boy teach the woman to respect him. Rather, George attempts to poison the old dear, and when this is only partially successful, his father conspires to help her take too much of the antidote, to the point where she doesn’t so much die as shrink out of existence.

At this point her own daughter, rather than express any regret at her passing, concedes she was something of a nuisance to have around the house.

The transgressive nature of the best children’s literature, its ability to celebrate out loud that which cannot be thought in public, is a thing to be savoured. As is the view in the rear-view mirror, of two delightful boys, lost in story, cackling together, becoming human.

Looking Where I’m Standing

Felicity Castagna

Sandra Cisneros taught me that the parking lot in the image on the previous page is something extraordinary and that idea made me a better writer and a better human being.

Cisneros’ s book The House on Mango Street (1984) is the story of a Latina girl named Esperanza Cordero who spends her time living in too many different places as a child until her family of six finally buys a small house on Mango Street in a friendly but often rough neighbourhood of Chicago. This young adult novel is told in the vignette form – a kind of short, short story that uses highly poetic imagery to focus on a small place and moment in time. The book uses the vignette style to take us from a little house and out into the streets where small things are examined and their larger significance unravelled: the peeling red paint of a too-small house, the swaying hips of women as they strut down the street, the bike all the neighbourhood children take turns riding, the woman who stares out the window of her house because her husband thinks she is too beautiful to be let out, the tired-looking men who hang out with each other on street corners.

It’s a book about a lot of things but to me it is most importantly a book about place, about community and the importance of thinking deeply about where you are standing. Somehow this book has always managed to show up in my life whenever I needed it. When I first read this book in my Year Nine English class I was Esperanza – an awkward lonely girl whose family had moved so many times, across state and national borders, and all I wanted in life was my own “house on Mango Street” where I could have a place to be for a while. In my twenties the book came back again several times, always at the right time, following me around by showing up in garage sales, the bookshelves at strangers’ parties and once, I kid you not, beside me on a train. And still now I dip in and out of its pages every time I get too busy or too distracted and forget to notice what’s going on around me.

My first young adult novel, The Incredible Here and Now, emerged out of so many years of thinking about The House on Mango Street, not just about what I could learn from it as a writer, but for what it taught me about the importance of observing the everydayness of the place you live in. Good writing about place comes from this observation of detail; from extracting the extraordinariness out of these ordinary things, like empty parking lots, that we see every day but sometimes fail to really notice. It presents us with more than just images – it gives us an invitation to experience the world we know in an entirely different way.

Working out how to belong in a place and how to write about it are for me very similar things. A sense of place applies most powerfully to the most commonplace and unremarkable things: the Pontiac that speeds down my street on weekdays at lunchtime, the vending machines in front of the Coke factory on my way to work, the Coles trolleys left by the river, the look of George’s rough hands as he bags my groceries at the corner store. Being from somewhere is about gathering these images, connecting memory to imagination; using these fragments to construct your own story of place.

Sometimes it’s really hard to remember to look at the place where you are standing. You can tell when you read The House on Mango Street that Cisneros has spent a lot of time walking, imagining, thinking. Writing about place is an expression of what is specific and local but it is also an expression of how we imagine the world that we live in. This is what I try to remember when I am writing about the western suburbs of Sydney; that when we write about places that are important to us we can change the way that outsiders imagine it. Change the imagination and you can change the world.

But what does this have to do with images of parking lots?

Parking lots are where life happens when you’re not thinking about it very much. So are backyards and side streets and apartment balconies. If you can’t find the extraordinariness that exists in these ordinary spaces you can’t be a writer. You can miss all these things because you’re not noticing, thinking, imaging. Being in the moment, being exactly where you are and looking at that giant arrow that points off into nowhere, that’s when you make those connections between story and life and life back to story. The House on Mango Street is a book that makes me look at where I’m standing over and over again and inspires me to write about it.

This World is More Than What Can Be Seen

Ambelin Kwaymullina

They’ve asked me to write about the book that made me. Only I can’t, because the story that made me, the one that flows through my mind and heart and veins, isn’t in a book. It’s a lot older than that. Older than the invention of the printing press; older even than the stone tablets of the Romans or the papyrus scrolls of the Egyptians. It is the tale of an ancient people in an ancient land.

The story of Aboriginal people in Australia begins in the Dreaming, when the creative Ancestors made the world and everything that exists within it now. The Ancestors came in different forms – rock and crow and dingo, the seven sisters who became stars, and many, many others. They shaped the different Aboriginal homelands of Australia, the places that we call our Countries, and they taught us how to sustain a living land. It is their stories that make all stories possible.

The Country of my people, the Palyku, lies in the Pilbara region of Western Australia. The Pilbara is a place of far horizons and vivid contrasting colours – red earth, purple hills, green gum trees and long blue skies. Like all Aboriginal Countries, my homeland is rich in story. The great libraries of the Aboriginal nations of this continent are not built of bricks or steel. Our knowledge is written into the land and our old people highly literate in reading the earth around them. But when strangers arrived on these shores, they did not understand our ways of knowing. And the arrival of the colonisers marked the beginning of another set of tales, the stories of the generations of Aboriginal people who lived the trauma of colonialism.

These tales, too, are part of the story that makes me, and they are tales of terror, of violence and hea

rtbreak. But they also tell of courage, of defiance, and of endurance against all odds and in the face of determined efforts to destroy. So many of those who survived what were among the worst of times, the men and women of my great-grandmothers’ generation, are people of boundless generosity of spirit. Their tales speak of what is perhaps the last choice anyone has left when all other options are stripped away – the choice to be better than the times in which you live or the way in which you are treated. And it is their incredible strength that makes possible the stories of all who came after.

The tale of who I am is formed by, and linked with, so many others. The Dreaming Ancestors created a reality where everything lives and everything connects in an ever-moving network of relationships. This world is more than what can be seen, perhaps even than what can be felt, and in such a place, it is wise to be respectful of the life around you. Everything has a story, and it is impossible to determine the millions of ways in which the tales of the different shapes of life who inhabit this earth intersect with our own. I worry about the species who are struggling to survive. What will my story become without the ancient wisdom of a Loggerhead Turtle, the fierceness of a Chuditch (quoll), or the gentleness of a Pilbara Olive Python? We humans cannot see far enough to grasp the extent to which we are all diminished by the loss of stories from this earth.

Aboriginal stories are found in many places. In Country, in our hearts, in song and art and dance. And in books, some of which are written in the ancient languages of this land. We are many voices, and I am proud to be among the Aboriginal storytellers of Australia. The stories I create are for children and teenagers, and much of what I write is about the future. It seems to me that the world can often be an unjust place, and those injustices impact most terribly on the young. Perhaps because of this, I am obsessed with the tale of what could be, with the possibility of a place where all stories are valued. I glimpse this future, sometimes. I see it in dreams, in books, and most of all in the actions of good-hearted people across the globe who do what they can to bring positive change to this planet.

I want everyone who will come after me to inherit an earth bursting with diversity – of species; of voices; of cultures; of ideas. And I know that the future is a story to which we all contribute. So look. Look ahead. What do you want to see happen? Will you let the world shape you, or will you shape the world? I know it can be hard, especially when choices are few and obstacles are many. But your life, your choices, your dreams – they matter. We can none of us know the extent to which our story will intersect with the stories of others. Find your path, and let no one diminish it, or you.

Every story matters, and we all have the power to influence the future.

What the Doctor Recommended

Queenie Chan

In order to talk about the book that made me, I must first talk about my cousin Munn.

Doctor Hing-Munn Ma, that is.

However, in my native Cantonese language, I’ve always called him Cousin Munn.

If Munn was not quite the person who made me, then he was the person who gave me the tools to shape myself into who I am today.

Many books that change lives often come with two people attached – the one who wrote the book, and the one who pressed that book into your hand, urging you to read it. Cousin Munn was one of the latter, and he had caught me at that most formative time of my life – when I was a young teenager.

By day, Doctor Munn is a mild-mannered emergency room (ER) doctor working at Queen Mary Hospital, in Pok Fu Lam, Hong Kong. By night, he is a wellspring of information on manga, anime and video games. He’s the type of guy who is always “in the know”. He knows all about the latest popular trends, and whatever he’s into at the moment, he will sell it to you like he’s a guru pitching spiritual enlightenment.

(He’s actually a really good salesman. Looks like the world gained a good doctor, but lost a potential cult leader.)

I was born in Hong Kong, in 1980. For the first few years of my life, I was reared on manga and anime, the Japanese terms for comics and cartoons. When I migrated to Australia in 1986, I lost touch with Doraemon, Urusei Yatsura and countless other manga, until my family started taking yearly trips back to Hong Kong. This started when I was ten years old, and it continues to this day.

On some of these trips, Cousin Munn would meet us at the airport, to take the kids out shopping for the latest cartoon books. This was in the mid-1990s, and he would take us to massive, four-storey shopping centres in Mong Kok, where every. single. shop. sold either manga, anime or video games.

To me, this was Cool Central.

Cousin Munn would then sweep the shelves, buying me the latest popular manga in the name of “cultural education”.

(The adults, meanwhile, would gratefully check into the nearest hotel, eager to sleep off the jet lag. We would return from our shopping trip, and my parents would wake to find the hotel room wall to wall with all my new manga and video game purchases.)

As an overly serious ten year old, I looked up to Cousin Munn (the man!) as an arbiter of good taste. I knew that whenever he pointed his finger at anything pop culture related, there was bound to be something fun and interesting in that direction.

One day, he handed me a manga about a doctor.

Not a mad scientist, not Doctor Who, but a medical doctor.

A surgeon, in fact. The surgeon’s name was Black Jack, which was, not coincidentally, also the name of the manga series.

Well, it’s no surprise that a doctor would recommend a manga about a doctor; people love seeing themselves reflected in fiction. However, my own interests sat squarely in fantasy – knights, wizards and demon kings battling it out in epic battles of good and evil. I was around fifteen at the time, and in the Queenie-verse, manga was only ever about two things: swords and sorcery fantasy realms, or high school romances (with or without vampires).

I pretended I was happy and interested in Black Jack, but really, I wasn’t. I knew what kind of art and stories I liked, and this was neither. The art, especially, was weird. It was old-school cartoony and unappealing, and Black Jack himself looked like a cross between Cruella de Vil and Dracula. Of course, Cousin Munn must have sensed this, because he rolled out his famous sales pitch.

According to him:

Black Jack is a riveting tale about a rogue surgeon, a medical maverick whose talents are highly sought after.

He’s a genius in his field, but unlicensed, because he would charge his clients exorbitant fees, which was, well, unethical.

Black Jack is about this man and his shadowy past, but also his patients, and the strange real-life illnesses they have to deal with.

… And, it’s by the same author as Astro Boy.

For a brief moment, life returned to my eyes. I recalled the brave little boy robot with rockets for legs, horns for hair and a machine gun for a butt. I had religiously watched the Saturday morning cartoon as a kid in Sydney, and even fifteen year olds were capable of feeling nostalgia.

I gave Cousin Munn a huge smile, thanked him, and then shoved Black Jack right to the bottom of my reading pile.

Needless to say, I then went right back to the hotel and ploughed through all my new action adventure and swords & sorcery manga.

My favourite manga were Dragon Ball Z and Dragon Quest at that time (I was obsessed), and my mind was preoccupied by high-stakes mid-air battles between warriors blasting each other with huge energy balls. There was no room left in my mind for a quiet story about an unethical surgeon. Not even one who will undoubtedly turn out to have a heart of gold and a core of inner strength.

As anyone who’s ever read manga will know, you can easily get through ten volumes of manga in a little under four hours. That was exactly what happened, when I found myself staring at the last book in my pile – Black Jack.

It would be a huge cliché to say that this book “changed my life”. It’s probably more appropriate to say that this book “opened a door”.

The crucial lesson I

learned from reading Black Jack is that a good storyteller can make any story interesting.

Black Jack was a series of short stories with recurring characters, and Munn was right when he called it riveting. There were no formulas in the world of Black Jack, or at least none I could easily predict. The endings were not always happy, and the patients Black Jack cured sometimes didn’t really want to be cured.

In short, these were stories about humanity. People who behaved in unpredictable ways, as people often do, for reasons they sometimes don’t fully understand themselves.

Some of them were honourable and some of them were weak, but all of them had reasons I could comprehend and even feel sympathetic towards.

Reading those stories in that little hotel room, it made me realise the limitations of doctors – what they ultimately can do, and cannot do. I used to believe that doctors were “lifesavers”, angels who swooped in to rescue people on the brink of death, but it turned out to be more complicated than that. Truth is, sometimes people didn’t want to be saved, and sometimes they couldn’t be saved – even from themselves. Doctors can’t force their patients to see things differently. They can only take the lead, pointing in the right direction and hoping their patients will see things their way.

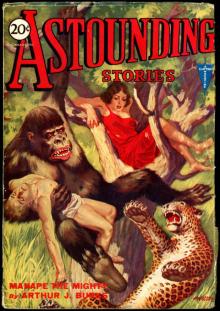

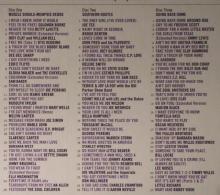

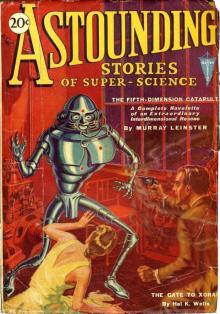

Astounding Stories, March, 1931

Astounding Stories, March, 1931 Astounding Stories, February, 1931

Astounding Stories, February, 1931 Futuria Fantasia, Spring 1940

Futuria Fantasia, Spring 1940 The King's Daughter and Other Stories for Girls

The King's Daughter and Other Stories for Girls Uncanny Tales

Uncanny Tales Masters of Noir: Volume Two

Masters of Noir: Volume Two Witty Pieces by Witty People

Witty Pieces by Witty People Sylvaneth

Sylvaneth Space Wolves

Space Wolves Hammerhal & Other Stories

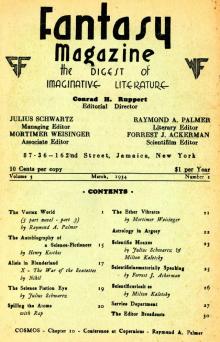

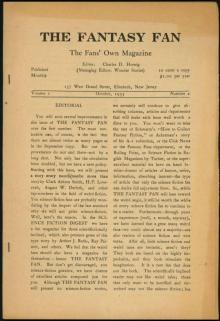

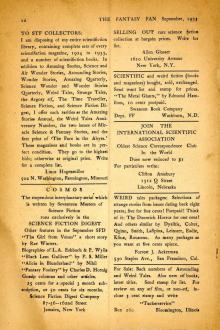

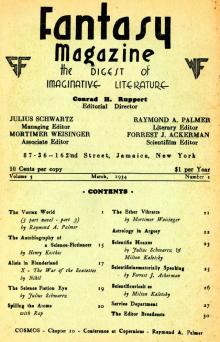

Hammerhal & Other Stories The Fantasy Fan, March, 1934

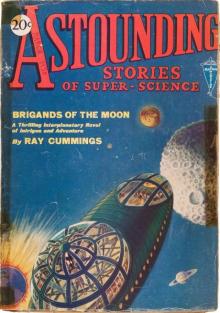

The Fantasy Fan, March, 1934 Astounding Stories of Super-Science, August 1930

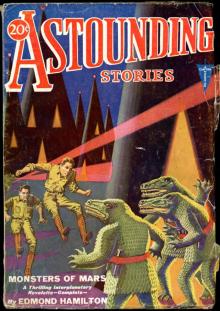

Astounding Stories of Super-Science, August 1930 Astounding Stories, August, 1931

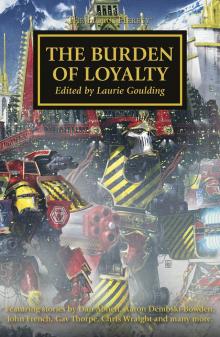

Astounding Stories, August, 1931 The Burden of Loyalty

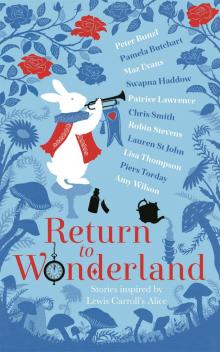

The Burden of Loyalty Return to Wonderland

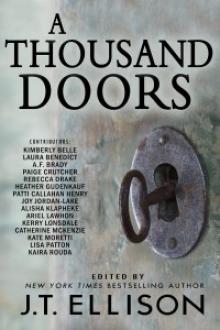

Return to Wonderland Anthology - A Thousand Doors

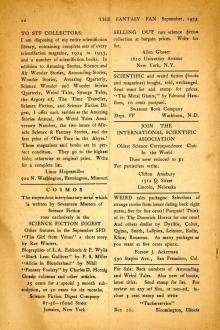

Anthology - A Thousand Doors The Fantasy Fan, October 1933

The Fantasy Fan, October 1933 Astounding Stories, June, 1931

Astounding Stories, June, 1931 Southern Stories

Southern Stories Astounding Stories of Super-Science, May, 1930

Astounding Stories of Super-Science, May, 1930 The Fantasy Fan December 1933

The Fantasy Fan December 1933 Adventures in Many Lands

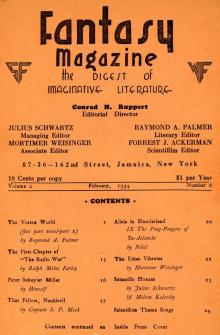

Adventures in Many Lands The Fantasy Fan February 1934

The Fantasy Fan February 1934 The Fantasy Fan November 1933

The Fantasy Fan November 1933 Astounding Stories, April, 1931

Astounding Stories, April, 1931 Fame and Fortune Weekly, No. 801, February 4, 1921

Fame and Fortune Weekly, No. 801, February 4, 1921 Astounding Stories of Super-Science, November, 1930

Astounding Stories of Super-Science, November, 1930 Astounding Stories of Super-Science January 1931

Astounding Stories of Super-Science January 1931 A Monk of Fife

A Monk of Fife Astounding Stories of Super-Science September 1930

Astounding Stories of Super-Science September 1930 Astounding Stories of Super-Science July 1930

Astounding Stories of Super-Science July 1930 Astounding Stories of Super-Science, June, 1930

Astounding Stories of Super-Science, June, 1930 Astounding Stories of Super-Science, October, 1930

Astounding Stories of Super-Science, October, 1930 Astounding Stories of Super-Science, March 1930

Astounding Stories of Super-Science, March 1930 The Fantasy Fan January 1934

The Fantasy Fan January 1934 The Fantasy Fan September 1933

The Fantasy Fan September 1933 Astounding Stories of Super-Science February 1930

Astounding Stories of Super-Science February 1930 Astounding Stories, May, 1931

Astounding Stories, May, 1931 Strange Stories of Colonial Days

Strange Stories of Colonial Days Golden Age of Science Fiction Vol IX

Golden Age of Science Fiction Vol IX Astounding Stories of Super-Science, December 1930

Astounding Stories of Super-Science, December 1930 Evolutions: Essential Tales of the Halo Universe

Evolutions: Essential Tales of the Halo Universe Good Stories Reprinted from the Ladies' Home Journal of Philadelphia

Good Stories Reprinted from the Ladies' Home Journal of Philadelphia Dragons!

Dragons! Murder Takes a Holiday

Murder Takes a Holiday Legacies of Betrayal

Legacies of Betrayal STAR WARS: TALES FROM THE CLONE WARS

STAR WARS: TALES FROM THE CLONE WARS Strange New Worlds 2016

Strange New Worlds 2016 Lippincott's Magazine, August, 1885

Lippincott's Magazine, August, 1885 Golden Age of Science Fiction Vol X

Golden Age of Science Fiction Vol X Hot Stuff

Hot Stuff Santa Wore Spurs

Santa Wore Spurs Paranormal Erotica

Paranormal Erotica Tangled Hearts: A Menage Collection

Tangled Hearts: A Menage Collection Sweet Tea and Jesus Shoes

Sweet Tea and Jesus Shoes The Journey Prize Stories 25

The Journey Prize Stories 25 Wild Western Tales 2: 101 Classic Western Stories Vol. 2 (Civitas Library Classics)

Wild Western Tales 2: 101 Classic Western Stories Vol. 2 (Civitas Library Classics) (5/15) The Golden Age of Science Fiction Volume V: An Anthology of 50 Short Stories

(5/15) The Golden Age of Science Fiction Volume V: An Anthology of 50 Short Stories (4/15) The Golden Age of Science Fiction Volume IV: An Anthology of 50 Short Stories

(4/15) The Golden Age of Science Fiction Volume IV: An Anthology of 50 Short Stories Ten Journeys

Ten Journeys The Boss

The Boss The Penguin Book of French Poetry

The Penguin Book of French Poetry Golden Age of Science Fiction Vol VIII

Golden Age of Science Fiction Vol VIII His Cinderella Housekeeper 3-in-1

His Cinderella Housekeeper 3-in-1 The Magazine of Fantasy & Science Fiction - July/August 2016

The Magazine of Fantasy & Science Fiction - July/August 2016 PYRATE CTHULHU - Tales of the Cthulhu Mythos (vol.2)

PYRATE CTHULHU - Tales of the Cthulhu Mythos (vol.2) Tales from a Master's Notebook

Tales from a Master's Notebook April 1930

April 1930 New Erotica 6

New Erotica 6 Damocles

Damocles The Longest Night Vol. 1

The Longest Night Vol. 1 The Golden Age of Science Fiction Volume VI: An Anthology of 50 Short Stories

The Golden Age of Science Fiction Volume VI: An Anthology of 50 Short Stories (1/15) The Golden Age of Science Fiction: An Anthology of 50 Short Stories

(1/15) The Golden Age of Science Fiction: An Anthology of 50 Short Stories Eye of Terra

Eye of Terra ONCE UPON A REGENCY CHRISTMAS

ONCE UPON A REGENCY CHRISTMAS Nexus Confessions

Nexus Confessions Passionate Kisses

Passionate Kisses War Without End

War Without End Doctor Who: Time Lord Fairy Tales

Doctor Who: Time Lord Fairy Tales Gotrek and Felix: The Anthology

Gotrek and Felix: The Anthology WESTERN CHRISTMAS PROPOSALS

WESTERN CHRISTMAS PROPOSALS The Journey Prize Stories 27

The Journey Prize Stories 27 The Silent War

The Silent War Liaisons

Liaisons Ellora's Cavemen: Tales from the Temple IV

Ellora's Cavemen: Tales from the Temple IV Ellora's Cavemen: Tales from the Temple II

Ellora's Cavemen: Tales from the Temple II Some of the Best From Tor.com, 2013 Edition: A Tor.Com Original

Some of the Best From Tor.com, 2013 Edition: A Tor.Com Original Urban Occult

Urban Occult Fractures

Fractures The Stories: Five Years of Original Fiction on Tor.com

The Stories: Five Years of Original Fiction on Tor.com The Penguin Book of Modern British Short Stories

The Penguin Book of Modern British Short Stories Mortarch of Night

Mortarch of Night The Portable Nineteenth-Century African American Women Writers

The Portable Nineteenth-Century African American Women Writers The Golden Age of Science Fiction Volume VII: An Anthology of 50 Short Stories

The Golden Age of Science Fiction Volume VII: An Anthology of 50 Short Stories Holy Bible: King James Version, The

Holy Bible: King James Version, The Eight Rooms

Eight Rooms sanguineangels

sanguineangels DarkNightsWithaBillionaireBundle

DarkNightsWithaBillionaireBundle Casserole Diplomacy and Other Stories

Casserole Diplomacy and Other Stories How I Survived My Summer Vacation

How I Survived My Summer Vacation Alfred Hitchcock Presents: 16 Skeletons From My Closet

Alfred Hitchcock Presents: 16 Skeletons From My Closet Lords, Ladies, Butlers and Maids

Lords, Ladies, Butlers and Maids The B4 Leg

The B4 Leg Ellora's Cavemen: Tales from the Temple I

Ellora's Cavemen: Tales from the Temple I 2014 Campbellian Anthology

2014 Campbellian Anthology There Is Only War

There Is Only War Obsidian Alliances

Obsidian Alliances 12 Gifts for Christmas

12 Gifts for Christmas Scary Holiday Tales to Make You Scream

Scary Holiday Tales to Make You Scream 25 For 25

25 For 25 The Plagues of Orath

The Plagues of Orath And Then He Kissed Me

And Then He Kissed Me Star Trek - Gateways 7 - WHAT LAY BEYOND

Star Trek - Gateways 7 - WHAT LAY BEYOND Laugh Your Head Off Again and Again

Laugh Your Head Off Again and Again The Balfour Legacy

The Balfour Legacy Golden Age of Science Fiction Vol XI

Golden Age of Science Fiction Vol XI (3/15) The Golden Age of Science Fiction Volume III: An Anthology of 50 Short Stories

(3/15) The Golden Age of Science Fiction Volume III: An Anthology of 50 Short Stories Shas'o

Shas'o Astounding Science Fiction Stories: An Anthology of 350 Scifi Stories Volume 2 (Halcyon Classics)

Astounding Science Fiction Stories: An Anthology of 350 Scifi Stories Volume 2 (Halcyon Classics) Twists in Time

Twists in Time Meduson

Meduson The Magazine of Fantasy & Science Fiction - August 1980

The Magazine of Fantasy & Science Fiction - August 1980 The Journey Prize Stories 22

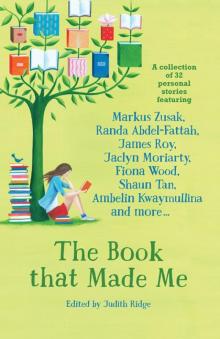

The Journey Prize Stories 22 The Book that Made Me

The Book that Made Me Angels of Death Anthology

Angels of Death Anthology Ask the Bones

Ask the Bones Emergence

Emergence Beware the Little White Rabbit

Beware the Little White Rabbit Xcite Delights Book 1

Xcite Delights Book 1 Where flap the tatters of the King

Where flap the tatters of the King The Journey Prize Stories 21

The Journey Prize Stories 21 Tales of the Slayer, Volume II

Tales of the Slayer, Volume II Glass Empires

Glass Empires Golden Age of Science Fiction Vol XII

Golden Age of Science Fiction Vol XII (2/15) The Golden Age of Science Fiction Volume II: An Anthology of 50 Short Stories

(2/15) The Golden Age of Science Fiction Volume II: An Anthology of 50 Short Stories Fairytale Collection

Fairytale Collection Angels!

Angels! Golden Age of Science Fiction Vol XIII

Golden Age of Science Fiction Vol XIII