WESTERN CHRISTMAS PROPOSALS Read online

Page 7

She sat with Mr. Avery and sewed, determined to have the pretty thing finished by the time Ned carried in the milk bucket late in the afternoon. He had insisted on doing her chores so she could finish the cravat, even though she knew it was seven miles to Medicine Bow and the dance started at nine o’clock. She handed the cravat to him after the last stitch.

“No one will have a cravat this fine,” he said, and held it up to his neck. “I have an ironed shirt, too.”

Her heart nearly stopped when he took her hand and kissed it. Impulsively she put her free hand on his head for no reason, except that she wanted to touch the man who had been so kind to her. He had helped her when he had no idea if she would steal the spoons in his house and vanish the next day, and he had built her a room. Her heart was full.

Kate wiped her eyes. “Go find someone nice,” she whispered. “I’d better read to your father while you take a bath in the kitchen.”

“You won’t scrub my back?” he teased.

“Not for thirty dollars a month,” she said, and he laughed.

* * *

A fellow could hope, Ned told himself, after he filled the galvanized tub in the kitchen and eased himself in for a quick soak, which turned into a longer one, because he had not enjoyed such luxury since his visit to Cheyenne. Ordinarily, a fast wash at the bowl and pitcher in his room sufficed. He sat so long in the cooling tub that he could have used one more bucket of hot water from the cooking stove’s reservoir. He doubted Kate would pour him one, but he could ask.

She surprised him by coming to the doorway of the kitchen, her head averted. “Another bucket?” she asked, and he heard the timidity in her voice.

“Yes, please. I’ll cover up. Just pour it behind my back,” he said, and hunched over his middle, his washcloth in place.

She did as he said. His hair was already damp so he lathered in soft soap. “If you could dip out half a bucket of hot water, and add an equal amount of cold from the kitchen pump, I can rinse this.”

“I’ll help,” she said, sounding businesslike. “A body can’t rinse his own head.”

Kate rinsed his hair without a complaint, even though it took two buckets to meet her apparently exacting standards.

“There. If you can’t manage the rest of this bath, you’re too young to go to a dance,” she scolded.

He sat a little longer in the water, wishing he could stay at home and listen to more of Lucie Manette, Charles Darnay and Sydney Carton, too, as read by his chore girl to his dying father who had taken on a new lease on life. Ned had enjoyed the book years earlier, but there was something almost royally sinful about having enough time to listen to another read it. Ned almost resented losing an evening at a dance, when he could be home, lying beside his father, listening to Katie read.

Or maybe he just didn’t want to dress up and ride through the dark to a dance where there might not be anyone young and even remotely eligible, Wyoming being what it was. I’m getting set in my ways, he thought. Kate is kind to rescue me.

Katie had managed to repair his one pathetic collar, stiffening it, and sewing it together to fit on his shirt. He called to her to button his new cravat in the back. He sat down on the corner of his bed so she could reach him. When she finished, she told him to stand up and turn around so she could adjust the handsome bit of brocade to suit herself. She stood back for a better look, and finally nodded her approval.

“You’ll do,” she told him as he put on his vest. She helped him into his black coat, smoothing the back of it near his shoulders. He liked her touch, but what man wouldn’t?

“You’ll do? That doesn’t sound like a ringing endorsement,” he teased.

“It is in Maine,” she assured him. “I mean what I say.”

Ned stood in the doorway of his father’s room, hesitant to leave. He understood his reluctance as Katie looked back at him. He saw the pride in her eyes that looked a little like ownership, which bothered him not at all. He owed this whole evening to her.

As he mounted his horse and started for town, he had another idea, one that bore some thought: he really didn’t want to go dancing without Katie.

Chapter Fourteen

Medicine Bow must have grown during the past year. Ned Avery had no trouble filling out a dance card with a new schoolteacher in town, the banker’s daughter, a widow roughly his age who danced even better than Katie and the Presbyterian minister’s cousin from Ohio.

He remembered not to mumble one two three when he waltzed, came up with enough small talk to get him through a dance and stepped on nothing except the wooden floor.

By the time the dance ended, Ned had the name and address of the banker’s daughter, and had promised to take Sunday dinner with the minister’s cousin before she left for Ohio in the spring. The schoolmarm spent more time dancing with a rancher ten miles farther out of town; she’d find out soon enough he was a widower with five rowdy children.

Still, they weren’t Katie. Besides, if Katie had come with him, she could be filling up a dance card and looking over the local bachelors. She could also be dancing with him. He missed the sweetness of her breath on his neck when he whirled her around the kitchen.

He found himself comparing his dancing partners with Katie. Excepting the widow, none were as light-footed. The schoolmarm appeared as trim as Katie, but the whalebone corset he felt against his hand suggested otherwise. On the plus side, they were all easy to understand. He made a joke with the schoolmarm at Katie’s expense, imitating her Maine accent until the lady laughed, then felt ashamed of himself. Katie couldn’t help where she came from.

At three in the morning he went to bed in the hotel. He sat for a while on the edge of the bed, looking out at a full moon. He had a breakfast invitation from the Bradleys, provided he showed up by seven, so both Pete and Mr. Bradley could eat before they had to open the mercantile at eight.

He lay back finally, pleased with the way the evening had gone. He could tell Katie he had danced, conversed and looked over Medicine Bow’s promising females. He learned there would be a party on Christmas Eve with a real tree, sponsored by the Presbyterians.

He knew Katie would urge him to go, but as he lay there, the dissatisfaction which had dogged him all evening finally focused on the source of his discontent—Katie couldn’t go to the Christmas party, either. He had hired her to take care of his father, and there was no one else. His nearest neighbors had chatted with him at the dance, telling him they would attend the Christmas party, too.

He turned over, irritated at the unfairness of the deal he had struck with her. For a moment, he resented his father’s frailty. Pa had hung on so long, and now he even seemed to be getting better on Katie’s watch. She had promised to stay as long as his father needed her. What had sounded so simple a deal in Cheyenne wasn’t.

Once she was released, she would leave. There was nothing to tie her to his ranch. She had no burden of calving time, and beef prices and the fear of a dry summer.

He flopped on his back and stared at the ceiling. Pa had built the ranch from scratch, working horrible hours under difficult conditions, struggling through long winters, hot summers and Indian threats.

“I don’t have it in me,” Ned said aloud, voicing a fear that had teased him for months, ever since his father took sick.

The unfairness of his life bore down hard as he lay there. Because he lay there alone, Ned admitted to himself that he wanted to get on the train tomorrow and leave everyone behind. He could get a job in a warm place that didn’t require every ounce of his strength. He didn’t want this life his father had dumped in his lap.

Ned sat up and swung his bare legs over the side of the bed, disgusted with himself for such cowardice. He wanted to talk to Katie about it, to pour his troubles into her lap, simply because he knew she would listen. Maybe he just needed to share his misery with someone e

lse.

By skipping his daily shave, he made it to the Bradleys’ store and up the stairs in time for breakfast. There he sat, stupefied with exhaustion and trying to look interested as Pete described a typical day at the mercantile. Gradually, as what Pete was saying sank in, Ned pronounced a silent, grateful thank-you on Katie for acting on that help-wanted sign, something he would have ignored. Was he too stubborn to change?

“Pete suits us,” Mr. Bradley told Ned as the three of them trooped downstairs to the mercantile. “Don’t you, Pete?”

Pete nodded shyly, with a sidelong look at Ned.

“Then you’re all doing what the Lord intended,” Ned said, glad Pete had escaped from endless ranch work. No sense for both of them to be tied to the place.

He picked up a box waiting for him at the post office, the one bright spot in a day already going nowhere. “Hope you don’t think I’m getting ideas,” he said, looking down at the Montgomery Ward label.

“Ned, are you talking to parcels now?” he heard, and looked around to see the sheriff heading his way with something close to purpose in his stride.

“Only now and then, sir,” he said and waited for the sheriff.

“You need to know something,” the man said. “Name of Saul Coffin ring a bell with you?”

Chapter Fifteen

“Last I heard, he was dead and buried in Lusk,” Ned said.

“Turns out the guy in the coffin was someone at the Lucky Dollar who made fun of Mr. Coffin’s decidedly different accent,” the sheriff said. “Apparently the law in Lusk decided Mr. Coffin was acting in self-defense, when the drunk came at him.” He shook his head. “Drunks in a bar. Who is sober enough to know what went on?” The sheriff reached into his vest pocket. “Here’s a note from Mr. Coffin. Give it to the chore girl. Maybe she’ll straighten him out.”

My job just got harder, Ned thought. He gave the sheriff two fingers to his hat brim, and started home down a road that seemed suddenly unfamiliar.

I can’t lose her. How will I manage? fought with, This will please her no end. He patted the note in his pocket and decided that it could wait until he felt like handing it over. He knew he didn’t feel like it now. His whole middle-of-the-night irritation came crowding back.

Give it to the chore girl, the sheriff had said. Ned asked himself when she went from being a chore girl to being Katie, the woman who wanted a room of her own, but never locked her door; who used the last tangible memory of her real father to make him a cravat; who read A Tale of Two Cities aloud to his father; who took care of things at home so he could ride to Medicine Bow for some well-deserved fun, and all for thirty dollars a month and a place to stay.

He wondered what would happen when she came to the end of Dickens’s novel, where poor Sydney Carton sacrificed himself for another woman’s husband. He knew Katie would cry. To his knowledge, she hadn’t cried over Saul Coffin, but he knew she would cry over Sydney Carton. Because he knew that, Katie was his responsibility, too.

Never had a responsibility sat so lightly on his shoulders. He wanted to be there because she was in his house, taking quiet care of his father and him. She never complained. She did what was asked of her and slept in her bed each night, securely safe because she knew he would do her no harm. She had said as much and she was right.

What had gone from an impulsive agreement for her help until his father died had changed into a longer game. His father was getting better under Katie’s good care. The window he had cut into his father’s room was only one of Katie’s changes. She had taught Ned to dance, found Pete a job that suited him, dug into the dark recesses of the clutter of cabinets and found his mother’s old spices. She was making them all better because she cared. I owe her a great debt, he thought.

His well-being lasted until he rode his horse onto the stretch of grass between the house and the barn. The object of his thoughts must have been watching for him because she threw open the kitchen door and ran into the yard, waving her arms.

He wanted to leap from his horse and grab her, until she got close enough for a good look at her face.

“My father?” he asked, as larger worries took over. “Is he dead?”

She shook her head, but there was no disguising her distress. She stood there, looking so small and alone, almost as if she feared what he would do to her. He reached out to her, and she backed up.

“Katie, hold still,” he said. “He’s alive?”

She nodded, but he saw all the worry and tension in her whole body. He wanted to put his arm around her, but she wasn’t having any of that. They walked side by side to the wide-open door, Katie giving him fearful glances as if to determine his mood. He had certainly never known her stepfather, but Ned Avery suddenly hated the man.

“What happened?” he asked. “Tell me now before I go back to his room.”

She took a deep breath. “Last night. I was reading out loud. He grabbed his chest and said he couldn’t breathe.” She bowed her head. “I’ve never been so scared!”

He didn’t care what she thought as he flung off his coat and put his arm around her. “I shouldn’t have left you alone,” he said, but she stopped him with a thump to his chest.

“Don’t do that!” she exclaimed. “You never get away.” Her head went up. “I did as you told me to do. I...I found that bottle of glycerol...glycerol...”

“...trinitrate...” he finished, and started them both down the hall. “You put a tablet under his tongue?”

“Just like you said,” she told him. “He calmed right down.”

He stopped her at her room and put his hands gently on her shoulders, not willing to startle her, but not eager to let her go. “Then you did everything I would have done, Katie Peck,” he said. He saw the dried tears on her face and wanted to touch them. “But you felt pretty lonely, didn’t you?”

She seemed to know exactly what he was telling her. The fear left her face, replaced by tenderness. “And you’ve been doing this for how long?” she asked softly. “All alone, even with Pete here?”

“All alone.”

She gave him that level look, that calm glance of a realistic woman. She knew exactly how hard life was, and she had borne up under it, just as he had.

“As long as I am here, you’re not alone,” she told him.

He wanted to hold her in his arms, but his father called to him. Ned hurried down the hall to his father’s room.

His father lay there, eyes half-open, but calm. He had stuck his finger in A Tale of Two Cities, probably where Katie had dropped the book when she heard his horse.

“Madame Defarge spends all her spare time knitting and watching aristocrats lose their heads,” Dan Avery said, by way of greeting. “Did you meet any promising women? I hope Katie didn’t gussy you up for nothing.”

Ned lay down beside his father, his boots on the bed, which he knew would irritate Katie. Yes, he had met a promising woman. She lived in his house, he paid her thirty dollars a month and he had a letter in his pocket from her fiancé. I live a life too simple for so much drama, he thought in mild amusement. And what did I do but fall in love?

“I have a dinner invitation and an address I’m not sure what to do with. The schoolteacher resisted my charms, but you should see the preacher’s daughter. Pete is doing fine at the Bradleys, and you gave Katie quite a fright, Pa.”

“Couldn’t seem to help that,” his father agreed, and rubbed his chest.

Ned took a good look at Pa, wondering when he had got so thin. He took the book from his father. “Looks like the French Revolution is too much for you.”

His father managed a laugh. “I’ll tell you about Chickamauga and the Battle of Franklin sometime, and then we’ll see what’s too much for me.” His father rose up a little to look down the hall. “She did everything you would have done. You really just hired her o

n a whim?”

He nodded. “She stay up all night with you?”

“She did. I’m glad you’re home so she can sleep.”

He looked around. Where had she gone?

He found her in the barn. Katie sat at the milking stool, her head against the cow’s flank. Ned walked around to see her face, and her eyes were closed.

“Katie, go to bed,” he said softly.

She opened her eyes. “I’m not...”

She didn’t even get the word out before her eyes closed again. He moved her off the stool and into the hay and finished the morning milking, done late because she hadn’t left his father’s side. When he was done, he nudged Katie awake. Without a word, she stood up as dutifully as a child and followed him from the barn. The wind caught her and he heard her intake of breath.

After a glass of warm milk, some meat and broth from the stew simmering on the hob, Katie walked down the hall to her room and closed the door. He listened for the lock, and heard nothing except a yawn.

He brought his father a bowl of stew, and one for himself. Dan Avery finished first, after only a few mouthfuls.

“I scared her,” he said, “but you should have seen the determination in her eyes.” He chuckled. “She reminded me of you, and I knew then that I would live.”

What could he say to that? “I’ve been scared, too, Pa,” he admitted finally.

“Guess that’s three of us,” Pa replied. “Thing is, you don’t quit.”

You have no idea how much I want to, Ned thought.

Chapter Sixteen

I should get under these covers, Katie thought. I really should. She lay where she was, stupid with exhaustion. She thought she heard someone knock on her door, just a quiet tap.

“Yes?”

“Ned. Let’s talk.”

“Come in,” she said and sat up. Maybe her boss wouldn’t mind covering her feet at least. She asked herself why she wasn’t afraid to have him come into her room, especially after her insistence that she have her own room in the first place. She was either more tired than she thought, or she trusted him.

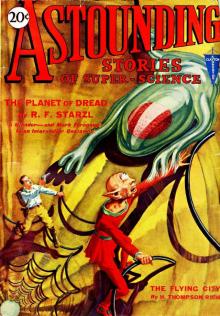

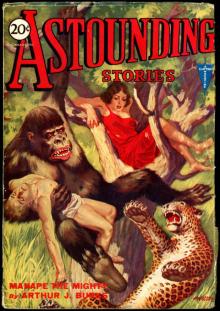

Astounding Stories, March, 1931

Astounding Stories, March, 1931 Astounding Stories, February, 1931

Astounding Stories, February, 1931 Futuria Fantasia, Spring 1940

Futuria Fantasia, Spring 1940 The King's Daughter and Other Stories for Girls

The King's Daughter and Other Stories for Girls Uncanny Tales

Uncanny Tales Masters of Noir: Volume Two

Masters of Noir: Volume Two Witty Pieces by Witty People

Witty Pieces by Witty People Sylvaneth

Sylvaneth Space Wolves

Space Wolves Hammerhal & Other Stories

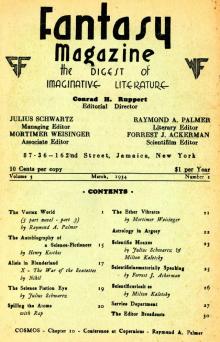

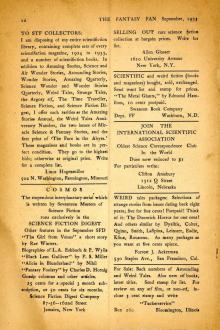

Hammerhal & Other Stories The Fantasy Fan, March, 1934

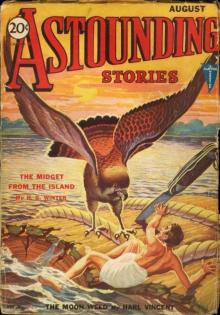

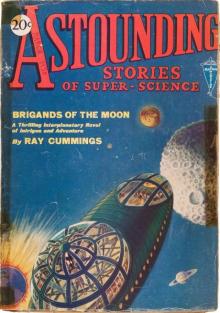

The Fantasy Fan, March, 1934 Astounding Stories of Super-Science, August 1930

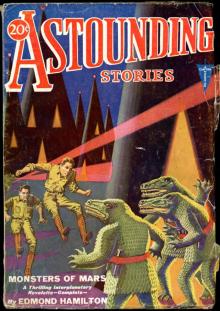

Astounding Stories of Super-Science, August 1930 Astounding Stories, August, 1931

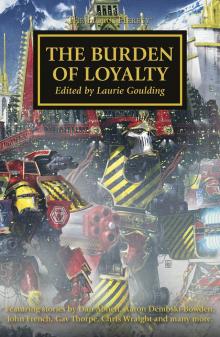

Astounding Stories, August, 1931 The Burden of Loyalty

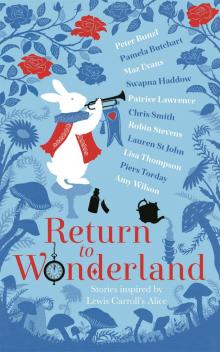

The Burden of Loyalty Return to Wonderland

Return to Wonderland Anthology - A Thousand Doors

Anthology - A Thousand Doors The Fantasy Fan, October 1933

The Fantasy Fan, October 1933 Astounding Stories, June, 1931

Astounding Stories, June, 1931 Southern Stories

Southern Stories Astounding Stories of Super-Science, May, 1930

Astounding Stories of Super-Science, May, 1930 The Fantasy Fan December 1933

The Fantasy Fan December 1933 Adventures in Many Lands

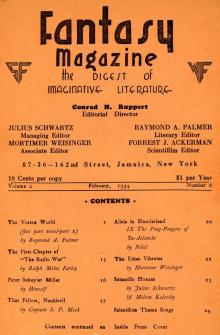

Adventures in Many Lands The Fantasy Fan February 1934

The Fantasy Fan February 1934 The Fantasy Fan November 1933

The Fantasy Fan November 1933 Astounding Stories, April, 1931

Astounding Stories, April, 1931 Fame and Fortune Weekly, No. 801, February 4, 1921

Fame and Fortune Weekly, No. 801, February 4, 1921 Astounding Stories of Super-Science, November, 1930

Astounding Stories of Super-Science, November, 1930 Astounding Stories of Super-Science January 1931

Astounding Stories of Super-Science January 1931 A Monk of Fife

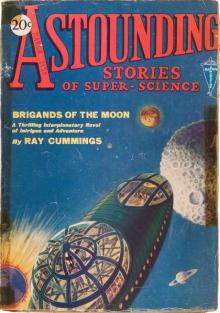

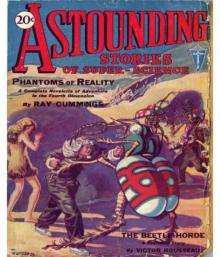

A Monk of Fife Astounding Stories of Super-Science September 1930

Astounding Stories of Super-Science September 1930 Astounding Stories of Super-Science July 1930

Astounding Stories of Super-Science July 1930 Astounding Stories of Super-Science, June, 1930

Astounding Stories of Super-Science, June, 1930 Astounding Stories of Super-Science, October, 1930

Astounding Stories of Super-Science, October, 1930 Astounding Stories of Super-Science, March 1930

Astounding Stories of Super-Science, March 1930 The Fantasy Fan January 1934

The Fantasy Fan January 1934 The Fantasy Fan September 1933

The Fantasy Fan September 1933 Astounding Stories of Super-Science February 1930

Astounding Stories of Super-Science February 1930 Astounding Stories, May, 1931

Astounding Stories, May, 1931 Strange Stories of Colonial Days

Strange Stories of Colonial Days Golden Age of Science Fiction Vol IX

Golden Age of Science Fiction Vol IX Astounding Stories of Super-Science, December 1930

Astounding Stories of Super-Science, December 1930 Evolutions: Essential Tales of the Halo Universe

Evolutions: Essential Tales of the Halo Universe Good Stories Reprinted from the Ladies' Home Journal of Philadelphia

Good Stories Reprinted from the Ladies' Home Journal of Philadelphia Dragons!

Dragons! Murder Takes a Holiday

Murder Takes a Holiday Legacies of Betrayal

Legacies of Betrayal STAR WARS: TALES FROM THE CLONE WARS

STAR WARS: TALES FROM THE CLONE WARS Strange New Worlds 2016

Strange New Worlds 2016 Lippincott's Magazine, August, 1885

Lippincott's Magazine, August, 1885 Golden Age of Science Fiction Vol X

Golden Age of Science Fiction Vol X Hot Stuff

Hot Stuff Santa Wore Spurs

Santa Wore Spurs Paranormal Erotica

Paranormal Erotica Tangled Hearts: A Menage Collection

Tangled Hearts: A Menage Collection Sweet Tea and Jesus Shoes

Sweet Tea and Jesus Shoes The Journey Prize Stories 25

The Journey Prize Stories 25 Wild Western Tales 2: 101 Classic Western Stories Vol. 2 (Civitas Library Classics)

Wild Western Tales 2: 101 Classic Western Stories Vol. 2 (Civitas Library Classics) (5/15) The Golden Age of Science Fiction Volume V: An Anthology of 50 Short Stories

(5/15) The Golden Age of Science Fiction Volume V: An Anthology of 50 Short Stories (4/15) The Golden Age of Science Fiction Volume IV: An Anthology of 50 Short Stories

(4/15) The Golden Age of Science Fiction Volume IV: An Anthology of 50 Short Stories Ten Journeys

Ten Journeys The Boss

The Boss The Penguin Book of French Poetry

The Penguin Book of French Poetry Golden Age of Science Fiction Vol VIII

Golden Age of Science Fiction Vol VIII His Cinderella Housekeeper 3-in-1

His Cinderella Housekeeper 3-in-1 The Magazine of Fantasy & Science Fiction - July/August 2016

The Magazine of Fantasy & Science Fiction - July/August 2016 PYRATE CTHULHU - Tales of the Cthulhu Mythos (vol.2)

PYRATE CTHULHU - Tales of the Cthulhu Mythos (vol.2) Tales from a Master's Notebook

Tales from a Master's Notebook April 1930

April 1930 New Erotica 6

New Erotica 6 Damocles

Damocles The Longest Night Vol. 1

The Longest Night Vol. 1 The Golden Age of Science Fiction Volume VI: An Anthology of 50 Short Stories

The Golden Age of Science Fiction Volume VI: An Anthology of 50 Short Stories (1/15) The Golden Age of Science Fiction: An Anthology of 50 Short Stories

(1/15) The Golden Age of Science Fiction: An Anthology of 50 Short Stories Eye of Terra

Eye of Terra ONCE UPON A REGENCY CHRISTMAS

ONCE UPON A REGENCY CHRISTMAS Nexus Confessions

Nexus Confessions Passionate Kisses

Passionate Kisses War Without End

War Without End Doctor Who: Time Lord Fairy Tales

Doctor Who: Time Lord Fairy Tales Gotrek and Felix: The Anthology

Gotrek and Felix: The Anthology WESTERN CHRISTMAS PROPOSALS

WESTERN CHRISTMAS PROPOSALS The Journey Prize Stories 27

The Journey Prize Stories 27 The Silent War

The Silent War Liaisons

Liaisons Ellora's Cavemen: Tales from the Temple IV

Ellora's Cavemen: Tales from the Temple IV Ellora's Cavemen: Tales from the Temple II

Ellora's Cavemen: Tales from the Temple II Some of the Best From Tor.com, 2013 Edition: A Tor.Com Original

Some of the Best From Tor.com, 2013 Edition: A Tor.Com Original Urban Occult

Urban Occult Fractures

Fractures The Stories: Five Years of Original Fiction on Tor.com

The Stories: Five Years of Original Fiction on Tor.com The Penguin Book of Modern British Short Stories

The Penguin Book of Modern British Short Stories Mortarch of Night

Mortarch of Night The Portable Nineteenth-Century African American Women Writers

The Portable Nineteenth-Century African American Women Writers The Golden Age of Science Fiction Volume VII: An Anthology of 50 Short Stories

The Golden Age of Science Fiction Volume VII: An Anthology of 50 Short Stories Holy Bible: King James Version, The

Holy Bible: King James Version, The Eight Rooms

Eight Rooms sanguineangels

sanguineangels DarkNightsWithaBillionaireBundle

DarkNightsWithaBillionaireBundle Casserole Diplomacy and Other Stories

Casserole Diplomacy and Other Stories How I Survived My Summer Vacation

How I Survived My Summer Vacation Alfred Hitchcock Presents: 16 Skeletons From My Closet

Alfred Hitchcock Presents: 16 Skeletons From My Closet Lords, Ladies, Butlers and Maids

Lords, Ladies, Butlers and Maids The B4 Leg

The B4 Leg Ellora's Cavemen: Tales from the Temple I

Ellora's Cavemen: Tales from the Temple I 2014 Campbellian Anthology

2014 Campbellian Anthology There Is Only War

There Is Only War Obsidian Alliances

Obsidian Alliances 12 Gifts for Christmas

12 Gifts for Christmas Scary Holiday Tales to Make You Scream

Scary Holiday Tales to Make You Scream 25 For 25

25 For 25 The Plagues of Orath

The Plagues of Orath And Then He Kissed Me

And Then He Kissed Me Star Trek - Gateways 7 - WHAT LAY BEYOND

Star Trek - Gateways 7 - WHAT LAY BEYOND Laugh Your Head Off Again and Again

Laugh Your Head Off Again and Again The Balfour Legacy

The Balfour Legacy Golden Age of Science Fiction Vol XI

Golden Age of Science Fiction Vol XI (3/15) The Golden Age of Science Fiction Volume III: An Anthology of 50 Short Stories

(3/15) The Golden Age of Science Fiction Volume III: An Anthology of 50 Short Stories Shas'o

Shas'o Astounding Science Fiction Stories: An Anthology of 350 Scifi Stories Volume 2 (Halcyon Classics)

Astounding Science Fiction Stories: An Anthology of 350 Scifi Stories Volume 2 (Halcyon Classics) Twists in Time

Twists in Time Meduson

Meduson The Magazine of Fantasy & Science Fiction - August 1980

The Magazine of Fantasy & Science Fiction - August 1980 The Journey Prize Stories 22

The Journey Prize Stories 22 The Book that Made Me

The Book that Made Me Angels of Death Anthology

Angels of Death Anthology Ask the Bones

Ask the Bones Emergence

Emergence Beware the Little White Rabbit

Beware the Little White Rabbit Xcite Delights Book 1

Xcite Delights Book 1 Where flap the tatters of the King

Where flap the tatters of the King The Journey Prize Stories 21

The Journey Prize Stories 21 Tales of the Slayer, Volume II

Tales of the Slayer, Volume II Glass Empires

Glass Empires Golden Age of Science Fiction Vol XII

Golden Age of Science Fiction Vol XII (2/15) The Golden Age of Science Fiction Volume II: An Anthology of 50 Short Stories

(2/15) The Golden Age of Science Fiction Volume II: An Anthology of 50 Short Stories Fairytale Collection

Fairytale Collection Angels!

Angels! Golden Age of Science Fiction Vol XIII

Golden Age of Science Fiction Vol XIII